Guantanamo’s Day In Court

by James Carroll

TOMORROW a number of the detainees held at Guantanamo Bay will finally get their day in court – although, alas, not literally. Thirty-five Americans who were arrested at the US Supreme Court last January during a demonstration protesting the illegal detention center will go on trial in Washington. They are charged with “causing a harangue.” Instead of entering their own names, each defendant will enter the name of a prisoner held at Guantanamo. Father Bill Pickard, a Catholic priest from Pennsylvania, will identify himself as Faruq Ali Ahmed. “He cannot do it himself,” Pickard says, “so I am called by my faith, my respect for the rule of law, and my conscience to do it for him.”

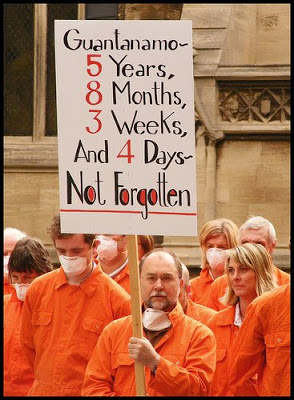

The protesters acted on Jan. 11, the sixth anniversary of the establishment of the US detention center at Guantanamo. They were demanding the restoration of habeas corpus – the right of the prisoners to have their day in court. Wearing orange jumpsuits and hoods, the protesters were decrying torture and degradation. The sleeplessness, waterboarding, insults to Islam. Some of the arrested were in the act of unfurling a banner that said with eloquent simplicity, “Close Guantanamo.” They broke the law because, despite widespread repugnance at what the Bush administration is doing in Cuba, the laws and institutions of the United States have so far abetted this criminal indecency.

Twice the US Supreme Court has ruled against Bush on Guantanamo (affirming habeas corpus for detainees in 2004, and ruling against military commissions in 2006), but Congress bailed Bush out with the Military Commissions Act in 2006. Over the years, Guantanamo has been criticized by human rights groups, other governments, the United Nations, associations of lawyers, and members of the military’s own judicial system. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and even Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates have both called for the detention center to be shut down. But it does not happen: Today there are nearly 300 prisoners there. Last week, the Justice Department inspector general released a report showing that FBI agents on the scene in Guantanamo have, over years, condemned the interrogation methods as illegal. “We found no evidence,” the report concludes, “that the FBI’s concerns influenced DOD interrogation policies.” No evidence, in sum, that the outrage at Guantanamo is being corrected by business as usual.

That is why, in an image offered by retired admiral John D. Hutson, the former judge advocate general of the Navy, the defendants “called artillery in on their own position” by engaging in civil disobedience at the Supreme Court. It was “heroic action,” Hutson said, “taken in a desperate situation for a greater good. That’s essentially what these 35 courageous Americans are doing.”

Can one break the law to uphold the principle of law? That will cease being the question tomorrow when the names of 35 incarcerated men are stated aloud in a courtroom – names that should have been spoken before a judge years ago. When that happens, the questions will become: Why are those men themselves not before a judge in a US court of law? And why are their torturers not charged with crimes? How is it possible that the American judicial system is itself protecting this rank violation of the American judicial system?

Last December, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Boumediene v. Bush, another case concerning the legal rights of Guantanamo Bay detainees. The ruling is to come, yet another opportunity for decisive intervention. But beyond the arcane, and so far impotent, redress-procedures of government lies the question of the broad US population’s attitude. Is the American commitment to basic rights really so shallow as to allow this travesty to continue? When did torture become acceptable? And once having widely denounced torture, what are citizens to do when it does not stop?

The group that goes on trial tomorrow calls itself “Witness Against Torture.” They are average folks from across the country. They could not stand it anymore. They did the only thing left for them to do. They went to Washington and caused a harangue. They purposely represent individuals held in torture cells. And, perhaps, they represent a lot of their fellow citizens, too. Close Guantanamo.

James Carroll’s column appears regularly in the Globe.

© 2008 The Boston Globe

Source / Common Dreams / Boston Globe

The Rag Blog