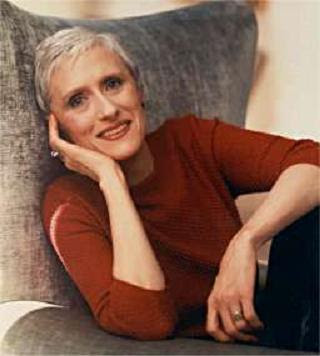

Sara Paretsky on her work and her politics.

By Matthew Rothschild

[This interview with mystery writer/social activist Sara Paretsky first ran in the March issue of The Progressive. The Rag Blog.]

I’m not a voracious reader of detective novels, but I wanted to meet Sara Paretsky. She’s the feminist crime novelist, based in Chicago, who is famous for her V. I. Warshawski series.

What impresses me about Paretsky’s work is how engaged she is politically. Bleeding Kansas has a subplot about opposing the Iraq War. Blacklist, which came out in 2003, deals not only with McCarthyism but also with the assault on our civil liberties in Bush’s post-9/11 America. “We were living in paranoid times,” her alter ego writes in Blacklist.

She is even more explicit in her recent memoir, Writing in an Age of Silence. “It is hard not to feel despair,” she declares, adding a little later: “I am tired. V. I. is tired, but we both need to get back on our horses.”

This tall, thin woman in a gray plaid suit with a grayish white scarf to match her hair overflowed with real-life stories she’s yet to put into print. She talked about a driver her publisher had once assigned to her, and what a nice man he was, though his entire family was in the mob. And she regaled me with stories about Bill Clinton, who has taken to sending her lengthy handwritten letters.

The weekend I talked with her, Paretsky received word that Writing in an Age of Silence was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

You mention being an organizer in Chicago in 1966 when Martin Luther King Jr. was there. What was that like?

Sara Paretsky: Organizer is kind of a grand term for what I was doing. I answered an ad that the Presbyterian Church of Chicago put up on college campuses. I was at the University of Kansas, and it’s somewhat relevant to my life and work that I’m a Jew. But they weren’t doing a religious litmus test. They wanted energetic, civil-rights-committed college students to come help them run some summer programs.

This was a very progressive group of clergy who foresaw the race riots that were going to take place when Dr. King started helping the local civil rights community push for open housing. They were sort of hoping against hope that we could educate kids in a way that could counter some of the racist messages they were imbibing at home. I don’t know whether we did any good, but it changed my life in every single way.

Q: How?

Paretsky: I had a fantasy as a child that I might be a writer someday. I always thought that meant you went to New York or Paris. But after that intense summer, I never thought that I wanted to live any place but Chicago. It also made me see what the stakes were in the civil rights movement. And it made me see what real hatred was like and the forms that it took. But it also made me understand how powerless ordinary people feel in their lives.

These events are swirling around them. In the white community, people felt like they had no control over their neighborhoods, their destiny. In the black community, centuries of government and economic forces were pushing on them. I went in with a kind of arrogance, maybe, that came from living in a very intellectual family, and I left knowing that there was a lot about the way people lived that I didn’t know about.

Q: How did you contend with that real hatred?

Paretsky: I have one vivid memory of one of the days that the marches were taking place. We were in a Catholic, predominantly Polish and Lithuanian neighborhood. Chicago is a place where people define themselves by their parish and by their ethnicity. When I tell people I was in the St. Justin Martyr parish, if they are native Chicagoans they know exactly where I was and what that was like. The Sunday before this particular march, the archbishop of Chicago, Cardinal Cody, had required all of his pastors to read a letter in support of open housing and economic justice in every parish in the city. And the fury in my community was just staggering.

The young priests in the parish were behind the message. The older priests weren’t necessarily, but they all followed the orders of the cardinal and read the letter. Every Sunday, 2,000 people came to mass at that parish. The following Sunday, the attendance dropped to 200, and never recovered.

The day of the march, we were forbidden to go to the march site. The man I worked for, the Presbyterian minister, knew we would want to be sort of martyrs for the cause and risk arrest. He didn’t want any of that going on. So he made us stay in the neighborhood. While we were walking around, we came to the Catholic church, and we saw that some people had set fire to carpets and banked them around the rectory, which was made out of wood. They knew every fire truck on the South Side was going to be in the park, that the rectory would just burn to the ground. Our one little act was putting out that fire.

Q: Did you get singed?

Paretsky: You know, I don’t remember. It would make a nice story if I said yes. But what I’ve learned is, when your adrenaline is flowing, you can do a lot. I’m not very physical, but once some punks were trying to break into my house and I chased them down.

Q: Sounds like a character in one of your novels. How did you become a crime novelist?

Paretsky: I sometimes think that I was like a sheep stumbling around in the dark. Yet the one common thing that I carried with me everywhere was loving crime fiction. I was in my early twenties when I first started reading American noir fiction, and that was when the women’s movement was starting to crest.

I was reading Raymond Chandler very much with the feminist eye. In six of his seven novels, it’s the woman who presents herself in a sexual way, who is the main bad person. And then you start reading more fiction, whether crime fiction or straight fiction, it’s just bad girls trying to make good boys do bad things, going all the way back to Adam and Eve. The woman that thou gavest me made me do it, Adam says to God.

So I began wanting to create a detective who really turned the tables on that image of women, to know that you could have a sex life and not be a bad person. You could have a sex life and still solve your own problems. It was eight years from when I started having the fantasy that I was going to create such a detective to when I actually sat down and came up with V. I. Warshawski. It was a long, slow journey to come to a writing voice and do that character.

Q: You say in your memoir that it’s hard for you to explore the characters of the wicked very well. Why?

Paretsky: Why is it hard for me to explore the character of people like Dick Cheney? When I see people with that much power, I don’t think of them as having believable foibles that are worth being empathetic with. They are just sitting on my head, making me feel helpless. When I look at Dick Cheney’s picture, I think, there is no soul there. He’s someone who has traded away everything that actually makes us human. So I guess that makes me not write about someone like him very humanly or perhaps very credibly.

Q: You write: “I cannot find words to express the depth of my loss or outrage about what’s happening to this country.” Can you find the words now?

Paretsky: I don’t know if I can find the words for it, but if this country ever recovers, it will not be in my lifetime. If I were elected President, the first thing I would do would be to set up a Department of Restoring the Bill of Rights. I would have 10,000 people working there.

Q: What is your view of Clinton and Obama?

Paretsky: I’m very torn. Barack was my state senator in Illinois, and I was one of his earliest supporters. I’ve always thought very highly of him. Here’s what I admire about Hillary: Every time I am going to walk away from her candidacy, I think, she has absorbed more hate than anyone I can think of over the past twenty years, and she hasn’t cracked under it. That’s a kind of iron fortitude that maybe we need in the President of the United States. People project on to Hillary because she is a woman. They either hate her for everything they hate about women or they long for her to be everything they want in a woman. It’s an impossible burden.

Q: On the other hand, Bleeding Kansas deals with the tragedy of the Iraq War, and Hillary Clinton voted for it. How do you wrestle with that?

Paretsky: Not at all easily. I worry about that. But I also worry about Barack and his “I will go one on one with all of these people.” There’s a certain kind of arrogance to that, either naiveté or arrogance, and both of them make me uncomfortable. I guess I don’t have a candidate who makes my heart go pitter-patter the way I wish it would.

I’m thinking, here’s an African American candidate—yes! And here’s a woman candidate—yes! Why can’t I get behind either one of them? Don’t tell me I have latent sexism or racism that I need to confront. I don’t believe that. I think we are so burned by the current situation that we want somebody that it isn’t possible to have. We want someone who definitely looks like the messiah.

Read all of it Here.