‘None of us knew it yet, but we Americans were about to be trapped in the history that Lyndon Johnson would make’

By Ronnie Dugger / August 22, 2008

The confrontation between Lyndon Johnson on one side and The Texas Observer and me on the other arrived on its own terms at his ranch in the Hill Country in 1955.

He was the senior United States senator from Texas and the new majority leader of the Democrats in the Senate. He had developed his concept of journalism as the editor of his college paper sucking up to the college president, and by 1955 he was hell-bent on the presidency. A group of national liberal Democrats and I, chosen as editor, had launched the Observer the preceding December. I had been editor of my high school and college newspapers, a sportswriter, columnist, an occasional correspondent for the San Antonio Express-News, and a hanger-out with Edward R. Murrow’s boys at CBS News in London when I was studying in England. Johnson was 47; I was 25.

None of us knew it yet, but we Americans were about to be trapped in the history that Lyndon Johnson would make, and I was about to be trapped in his persona and career. He was not an idealist, but he served ideals when it suited and expressed him. He was not a reactionary, but he fanned reaction when it helped him advance himself. As I wrote in my 1982 book about him, “Lyndon Johnson was rude, intelligent, shrewd, charming, compassionate, vindictive, maudlin, selfish, passionate, volcanic and cold, vicious and generous. He played every part, he left out no emotion; in him one saw one’s self and all the others. I think he was everything that is human. The pulsing within him, his energy, will, daring, guile, and greed for power and money, were altogether phenomenal, a continuous astonishment.” Ahead of us lay his ascension to the presidency after the assassination of John Kennedy and his calamitous Vietnam presidency, but also his presidency of Medicare, Medicaid, the Voting Rights Act, the Fair Housing Act, Head Start, federal aid for the education of the poor, bilingual education, affirmative action, and the establishment of public radio and television.

Lyndon was the driven son of an ambitious, all-empowering mother and a failed liberal politician who made it no higher than elected membership in the Texas House of Representatives. After a lot of hell-raising, Lyndon, following his mother’s lead, took $100 from his folks and enrolled at Southwest Texas State Teachers’ College in San Marcos. The 700 students there came from the farms and towns in the area. They were almost all white, only a few Mexican-American. Already aiming to be president, Lyndon was set on getting power even in school, and having watched his father, he knew how to try and how not to try for it. Since he got not another nickel from his parents, he had to work his way through Southwest Texas, but after a stint janitoring around the campus, he simply strode into the office of Cecil Evans, the president of the school, and talked his way into a slightly better job.

Walking on campus with his cousin Ava, Lyndon divulged to her his theory of how to get ahead. “The first thing you want to do,” he told her, “is to know people—and don’t play sandlot ball; play in the big leagues … get to know the first team.”

“Why, Lyndon,” she exclaimed, “I wouldn’t dare to go up to President Evans’ office.”

“That’s where you want to start,” he told her.

“I knew there was only one way to get to know him, and that was to work for him directly,” Johnson told me later in the White House. For most of his time at Southwest Texas, he was special assistant to the president’s secretary, with his desk next to the secretary’s. This paid him $37.50 a month, but he wanted to be editor of the student paper because that would pay him another $30.

In his first signed editorial in the student paper, the College Star, Lyndon rebuked fellow students—“celebrities,” he called them—who were using the college bulletin board for personal messages. The board “must be kept free for school matters,” he wrote, of course thereby pleasing Cecil Evans. Lyndon “knew how to ingratiate himself,” as one of the English teachers there said, and when the student council made him editor of the Star, he demonstrated further that he would use the paper as a tool for personal advancement. Profiling his own boss, Lyndon wrote: “Dr. Evans is greatest as a man,” what with “his depth of human sympathy . . . unfailing cheerfulness, geniality, kind firmness,” and so on.

Throughout his career on the make, Johnson cottoned up to selected powerful political leaders, both accommodating and abetting them, and thus predictably becoming a favored protégé. He did this, for example, with House Speaker Sam Rayburn, President Roosevelt, and Sen. Richard Russell, as well as with business leaders such as contractors George and Herman Brown. In flattering Dr. Evans in the college paper that he edited, he was just warming up his game of protegeship through the opportunities provided him by his temporary status as a journalist.

In 1955, Rayburn and Johnson, the Democratic Party’s bosses over the two branches of the distant Congress, were gigantic figures in one-party Texas politics. The Democrats in Texas were venomously divided between the “loyal Democrats”—also called national Democrats, who generally favored the policies advanced by Roosevelt and Truman—and the reactionary governor, Allan Shivers, and his fellow segregationists and conservatives, who had total control of the state Democratic Party. The previous October, a group of about 100 “loyal,” that is, national, Democrats in Texas, sensing that Shivers and his followers would go for Eisenhower for president in 1956 (as they did), gathered in Austin to found a liberal journal and asked me to edit it.

They knew, of course, that my views were liberal. They had some knowledge of my years of reporting on the thoroughly corrupt Texas Legislature in The Daily Texan, the student paper at the University of Texas in Austin, and my year as editor there championing racial integration, repeal of the oil depletion allowance, and other liberal causes. For a year my columns from abroad, laced with some of my policy opinions, had run in the San Antonio daily. A speech I had given to the Houston Rotary Club advocating, among other things, national health insurance, had provoked the physicians in the club to issue an outraged written objection.

Most of the liberals who had assembled in the hotel downtown, however, appeared to want a party organ, its editorial voice subordinated to the calculations of the national Democrats in Texas. My models for reporting were: the great muckrakers; Ed Murrow; James Reston. My idea of journalism included standing enough apart from government and political parties to report independently of them and to criticize any institution when that was called for. Although party organs have their place, I did not want to work on one.

Acting through Jack Strong, a lawyer in East Texas, the liberals offered me the editorship on the Friday before the Monday when I was leaving for Corpus Christi to work on a shrimp boat and jump ship in Mexico, eventually to write a novel about the Mexicans who (then as now) were wading, swimming, and drowning in the Rio Grande in search of work. That night I batted out a long letter to the group addressed to Mrs. R.D. Randolph, one of the group’s leaders who was an heiress to the Kirby lumber fortune in East Texas, outlining what sorts of stories I would want the Observer to investigate and what sorts of editorial crusades we likely would launch, but also my position on a party organ. Addressing the group in the hotel downtown, I told them I was not interested in editing a party organ, but I would stay and edit the new journal, provided I had exclusive control of all the editorial content. The paper’s publisher could fire me at any time for any reason, but as long as I was the editor, I would determine the editorial content. This arrangement, which protects the journalists and the journalism from politics or the business of publishing, I later, as Observer publisher until 1994, explicitly ceded to every editor who succeeded me.

Bob Eckhardt, the great legislator of my generation in Texas and soon to become one of my closest friends, told me later that a fierce debate occurred after I left the hotel. He said that Mark Adams, a New Dealer and a yeoman printer, said that “if ever a rattlesnake rattled before he struck, Dugger has.” Mark, who became my first printer at the Observer, denied saying it.

But they accepted my terms, and as we prepared to begin, I settled on a motto for the front-page masthead, Thoreau’s “The one great rule of composition is to speak the truth,” and wrote a policy credo that contained the sentence, “We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to the truth as we find it and the right as we see it.”

I had no sting out for Johnson, far from it. While a student at UT, I had worked downtown in Austin as a reporter and news announcer for his and Lady Bird’s radio station, KTBC. His senatorial office, that is, he, had helped me get a job in Washington one summer in the division of international organizations at the Department of State. Returning from abroad, I had applied unsuccessfully for a job on his Senate staff. I learned that Horace Busby, one of his top advisers, had said to him something like, “Ronnie’s not our kind of guy,” but I didn’t know that for many years.

The first year or so at the Observer, I was the only reporter and editor, and we had one subscription person. The founding group watched quietly as I did my best to begin to wreak havoc on racism, corruption, poverty, discrimination, and the rancidness of the plutocratic ideals blatted forth by the allegedly Democratic Gov. Allan Shivers. When I reported the racial murders of two black children in Mayflower, Texas, near Tyler, I was told that one of the Observer founders, Franklin Jones Sr., a very successful plaintiff’s lawyer in Marshall, exploded profanely on seeing my photograph of the body of one of the dead children on the front page: “Here I am working my ass off getting subscriptions for the Observer, and Dugger sends us pictures of dead Negroes all over the front page.” But if Franklin did say that, or something like it, he said nothing to me.

A new Democratic National Committee member from Texas had to be chosen, and it became known that Sen. Johnson had exerted his power to achieve the selection for that honor of the reactionary and racist Lt. Gov. Ben Ramsey, who presided as the dictator over the Texas Senate to the purring pleasure, protection, and profit of every corporate fat cat in the state, the oilmen most of all. In editorials, I damned Johnson to hell and back for it.

Johnson had been opposing the Texas liberals—on Ben Ramsey, by effectively favoring conservative Price Daniel over the liberal Ralph Yarborough for governor, and in other ways—to get Texas reactionaries behind him, or at least to quiet them down, for his candidacy for president, which Rayburn and he would soon make public. Nearly all of us at the Observer and all our readers were in agreement on a new drive to build a grassroots uprising of the liberal and populist Democrats to throw Ramsey and his ilk—Shivers, Sen. Daniel, the lot of them—into the Republican Party where they belonged. Obviously a Democratic Party answering to well-organized Democrats in the cities directly challenged and would at least diminish the boss-rule powers that Rayburn and Johnson exercised and enjoyed, and Johnson went to calling all of us involved in this organizing effort “the redhots.”

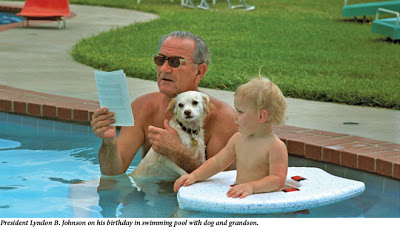

At some point that fall, with the Ramsey controversy smoking, I received a phone call that Sen. Johnson would like to see me, and would I call on him at the ranch at a certain hour on a certain afternoon. I had never been out there. After wheeling my family’s 1948 Chevrolet, which we called the Green Hornet, through the Pedernales River muscling itself shallowly over Johnson’s low-water bridge, I pulled up in front of his grand spread and saw that he was swimming in the pool, off to the right there. We greeted, nodding, and for some time I shifted from one foot to the other by the pool, feeling rather high in the air, as he continued his swim and, desultorily, we talked.

Toweling off and sitting us down on the pool furniture, cocking his long face toward me, Sen. Johnson asked me:

“Ronnie, what’s the circulation of your paper?”

“Oh, about 6,000.”

“Stick with me and we’ll make it 60,000,” Johnson said.

I knew at once what he meant. “Stick with me” meant support his policies and decisions, about Ben Ramsey and anything else, celebrate his sagacity and wisdom in all that I wrote about him, and support his presidential ambitions; “and we’ll make it 60,000” meant that in return, he would employ his standing, power, and connections to build up the Observer. The one great rule of composition would be to promote Lyndon Johnson. The Observer would be not a party organ, but a Johnson pipe organ that his nod could cause to bellow forth with Wagnerian splendor. The senior senator from Texas and the Democratic majority leader of the U.S. Senate had called me out here to propose straightforwardly that the Observer and I replace journalistic integrity with loyalty to him. He was trying to bribe me and The Texas Observer, or, if this was not to be a bribe, the deal—the secret understanding—the quid pro quo, obedient loyalty and feigned adulation in return for the other’s use of his power on your behalf, would have been not different from a bribe by a dime.

Johnson’s problem was, he would soon make public his campaign for the presidency. He knew the Observer was a novelty, conspicuous in reactionary Texas, reporting long-covered-up events and expressing unpredictable opinions; he knew that national newspeople, traipsing to and from his ranch from Austin, would often drop by the Observer offices for inside dope or just for the devilment of it, as in fact they were to do for the rest of the decade; and he knew that if his sellouts to the Texas yahoos and rednecks on the way to the White House became clear to the national Democrats, they might not nominate him for president.

My problem was how to get out of there. I could have just said, “I’m sorry, senator, no deal,” but this was not my style while practicing rebellious journalism in Texas. I extended myself and taxed my fellow Observer reporters to be fair and accurate, both in order to be fair and accurate and in self-defense, although, that done, in editorials I let miscreants and villains have it straight on. In person, in my life day after day, I was carefully polite and civil with all parties. If I was formally polite to a fault, well, it was a kind of protective coloration. On this afternoon with Johnson, I realized that the Observer and I had been misgauged and underestimated, but that for the rest of the occasion my part was to avoid any accusative remarks or implications, any incautious, offensive, or popinjay responses, and to graciously take my leave as soon as that might appear mannerly.

Sitting there side by side on plastic chaise lounges—someone brought us cold drinks, I believe lemonades—we talked along gingerly for maybe an hour. Well, senator, it’s an honor to have met you, and I appreciate your having me out—don’t want to overstay, I’d better be getting back to town—I said something like this, starting to rise to head back to my Green Hornet.

No, he said, why don’t you stay to dinner. No trouble, Bird’ll have plenty.

Although I had nothing more to say to him, I had not said no, and he had something more to say to me.

After an interim during which nothing happened, I sat down to dinner in a half-dark chamber at the center of the Johnsons’ well-staged home with Lady Bird Johnson and Johnson’s personal secretary, Mary Margaret Wiley, who had been my managing editor in high school in San Antonio when I had edited the Brackenridge Times. Mary Margaret is a beautiful person. While I had perceived no romantic flash in our friendship and work together in high school, we admired and respected each other; I was glad she was there.

As Johnson sat down at my left at the head of his table, though, I realized, silently appalled, “My God, the subject is at hand, all I can do is explain journalism to him as if he actually doesn’t know what it is.” If the situation had not been unbelievable, it would have been incredible.

I struck forth uncertainly, as if we were dining on a pitching log, addressing only Johnson to describe, as best I could, the role of journalism, the Fourth Estate, separation from government, providing facts and explanations, democracy’s inexpendable need for an independently informed electorate. I may even have quoted Jefferson. I might as well have been talking to the log I was riding. Johnson said to me, No, the thing a smart young reporter does, and should do, is survey the field of candidates, pick the best one, and enter into a deal to help that one win whatever office and prevail in whatever controversy, subordinating his reporting and comment to the interests of the candidate.

Johnson was far too smart to really think that is what journalism is or should be. He was feigning adherence to a theory of journalism, a blend of his own practice on his college paper and his political strategy of protegeship upended for the advance of his juniors, that might work somewhat, with me and others, as a disguise for his use of journalists to serve his will to power. Later it became embarrassingly clear that he had induced some of the leading reporters and columnists in Texas and the nation to make some such a deal with him or assent to some such understanding: Leslie Carpenter, William S. White, Joseph Alsop, some of the authors of those surprising articles in the big magazines in the late 1950s promoting the lanky Lyndon Johnson of Texas for president of the United States.

I remember (I am not referring, for this essay, to my notes on all of this) that neither Lady Bird nor Mary Margaret said one word all evening. Oh, perhaps one or two, but I don’t remember even one. They sat silent and still as good women of old were supposed to during an argument among the men. Yet both Bird and Mary Margaret were highly intelligent. How strange the evening must have seemed to them, their guy trying to turn a journalist into his secretly bought public promoter, their senator and this younger guy battling over irreconcilable opinions, completely missing each other, reaching no agreement.

Many’s the time since that evening there has replayed on the stage in my mind a vivid re-seeing of what happened upon my departure that evening. I am five or six feet away from Lyndon and me, watching the two of us illuminated by the ranch-house lighting locked in animated argument in front of his house at his low wire fence, he inside the fence, I outside, our knees braced against it and each other, intensely disputing directly into each other’s faces a few inches apart, he leaning first a little into my face, and then a little more, and then so much my head is bent back, and I shift my heels backward to be able to stand up straight to him again.

My first associate editor at the Observer, Billy Lee Brammer, a reporter on the Austin daily (and later the author of the classic Texas novel The Gay Place), started showing up unbidden evenings and helping me clip the 3-foot-high mounds of the rotgut Texas daily newspapers of that era, then quit downtown and came on staff. He flourished in reporting Texas politics for us, most memorably “the Port Arthur story” and the Austin lobby’s junket for Texas legislators to the Kentucky Derby, until Johnson hired him onto his Washington staff.

The liberal Democratic organizing of the ’50s caught hold in the cities, especially in Houston and San Antonio. In the 1956 Democratic state convention, over the furious objections of Johnson and his operatives there, the delegates elected Mrs. Randolph, who had become the de facto publisher of the Observer, to the Democratic National Committee. Four years later, favorite son Johnson trounced his opponents in Texas and swept into that year’s state convention, where he had Mrs. Randolph replaced. In one of these conventions, Mrs. Randolph told me, Johnson sent her word asking her to call on him, and when she did he asked expansively, “Well, Mrs. Randolph, what can I do for you?” She replied: “Nothing.”

Texas labor leaders Fred Schmidt and Hank Brown told me that, when they lobbied the Democrats’ Senate leader in Washington, he railed against the Observer and me, on some specified occasion with a copy of the journal on his desk. Mrs. Randolph said that when he asked her to get me to do something or other she replied, “Talk to him.” At least I could think, when for example I wrote a series of columns on the horrors of nuclear weapons, or during the Vietnam war when I ran a headline across the front page, “Will Johnson Bomb China?” that the man himself might be reading it.

During one state Democratic convention, I was running tandem some with Mark Sullivan, the Southwest bureau chief for Time-Life, for which I was a stringer. Mark and I approached Johnson on the convention floor for an interview. Johnson barked out that he wouldn’t talk to us with me there because “that boy prints lies about me.” We left him—or at least I did; I am not sure what Mark did.

That was the first and has been the only time in my life when I have directly experienced from another person the will to ruin me. The Time-Life connection was enabling me to hold up my financial end with my wife and children despite my annual Observer salary of $6,500. With this one ferocious remark to my boss at Time-Life, Johnson surely meant to kill me professionally. Deep in my convention story in the Observer, I reported the scene and what Johnson had said about me. I was deeply offended, and a year or two had to pass before my anger about it subsided. But Time-Life stood by me (in fact in 1961, after a lunch with Henry Luce, I was invited to join the staff of Time, which I did not).

In 1959, preparing a special focus for the Observer on Johnson’s candidacy for president, I asked him for an interview in Washington, and he granted it. I remember that on my way into his regal office as majority leader, I saw Mary Margaret at her desk, and we exchanged cautious smiles and slight nods when my eyes briefly met hers as I passed. The interview went well enough. This time I got the full Johnson treatment of persuasion, charm, raillery, and menace—stories, brags, ridicules of his colleagues, jokes, hands on my knees—again and again the leaning into my face.

Perhaps I should also record that, in the early 1960s when Johnson was vice president, I became a correspondent in Texas for the then-liberal Washington Post, and I intuitively suspect on the basis of the facts and context of what happened, but I have no evidence, that Johnson used his extremely close ties to that newspaper’s executives to have them eventually drop me.

The Observer never endorsed Johnson for president except in his contest with Barry Goldwater in 1964. In columns, I was for Estes Kefauver in 1956, Averell Harriman in 1960.

Except for an oblique column in the Observer full of obscurities after the confrontation at the ranch, this is the first report I have written about these events since they occurred half a century ago. Initially there was the off-the-record problem, but that’s gone now. I have not wanted to write about it, too, because how could I without being perceived as possibly self-serving? I relate them here now because the Observer editor asked me to.

In November 1965, I was one of the eight speakers who addressed the first massive demonstration against Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam war, and afterward I typed out a copy of my speech and sent it to President Johnson (the Observer ran the text of it). Johnson had George Reedy, then his press secretary, send me a note that “the President asked me to tell you he seeks no wider war,” the first time I saw or heard him hide behind that lying bromide.

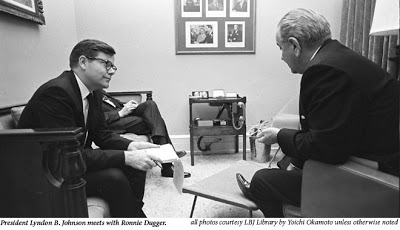

In 1967, having signed a contract with W.W. Norton for a book on Johnson, I wrote him asking him for biographical interviews and telling him that I intended a fair and accurate book worthy of the attention of serious people, and he gave me extensive interviews in the White House in late 1967 and 1968. He introduced me around the White House as “the leading liberal in the Southwest.” Discounting that as the Texas blarney it was, he had given off accusing me, or the Observer, of printing lies about him.

He tried to bring you into his field of overmastering personal power; that failing, he tried to ruin you; that failing, well, OK, he would deal with you again. In my last interview with him in the White House, on March 23, 1968, we were carrying along merrily. He was telling me a story when he suddenly interrupted himself and said, “Now, Ronnie, I’m giving you all these great stories, I want a friendly book!” I leaned forward and began, “Well, now, Mr. President—” but he shut me off and continued with the story. He was so charming, engaging, such an engrossing person, funny, fun to be with, such a good raconteur, I did not remember that he had said that until I was outside the White House that night. I went on back in and spoke with his press secretary then, my old friend George Christian, whom I had reported alongside years earlier in the offices of the International News Service in the Texas Capitol. I reminded George I had told Johnson I intended to write a fair and accurate book worthy of the interest of serious people, but that during our interview that evening he had said he wanted “a friendly book.” Oh, hell, George said, you know Lyndon, he didn’t mean anything by it. Maybe George was right, but “Yes, he did,” I said, “and please tell him from me, on that point, no deal.”

The next day, I suspected pro forma in light of what had occurred, I asked that my next interview with the president be scheduled, and then I waited some days in the Hay-Adams Hotel across Lafayette Park from the White House, where I was staying. No call came. A week later Johnson quit the presidency. Another week later, he began his interviews with Doris Kearns.

The Observer maintained its integrity and its independence of Lyndon Johnson before and during his presidency. He was who and what he was, the Observer and I were what and who we were and are, and this is the story of Lyndon Johnson, The Texas Observer, and me.

Ronnie Dugger, founding editor of the Observer and, later, its publisher until 1994, is the author of Dark Star, Hiroshima Reconsidered (World, 1967), Our Invaded Universities (W.W. Norton, 1973), The Politician: The Life and Times of Lyndon Johnson (W.W. Norton, 1982), and On Reagan (McGraw Hill, 1983). His work on stealing elections by manipulating computer-counted votes, beginning in The New Yorker and the Observer in 1988 and continuing since in other periodicals, initiated the reporting that predicted the potential for the current scandals and laid the foundation for needed reforms on that subject. He now works in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on books and his poetry; his e-mail is rdugger123@aol.com.

Source / Texas Observer