Two books on workers and rabble-rousing:

Kick some ass with the working class

By Ron Jacobs | The Rag Blog | April 25, 2012

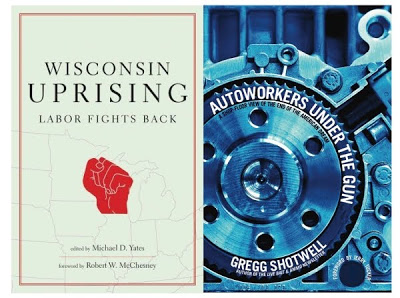

[Autoworkers Under the Gun: A Shop-Floor View of the End of the American Dream, by Greg Shotwell (2012: Haymarket Books); Paperback; 200 pp.; $17.00

Wisconsin Uprising: Labor Fights Back, edited by Michael D. Yates (2012: Monthly Review Press); Paperback; 288 pp.; $18.95.]

Damn. That’s the word I kept repeating as I read Gregg Shotwell’s recently published book Autoworkers Under the Gun.

The ugly side of being a factory worker in the U.S. auto industry is all here. Sociopathic CEOs, their lawyers, and the acquiescence of the UAW leadership, it’s all there.

This collection of newsletters written by a United Auto Workers activist documents the purposeful destruction of a union, an industry, and a way of life by bankers, corporate raiders and supplicant union bosses. The tale told here is about the daily fight on the shop floor.

Shotwell’s writing is humorous, acerbic, and to the point. As part of a democratic movement in the UAW, he was one of many that fought hard to prevent the tidal wave of layoffs, plant closings, and destruction of benefits the union leadership not only allowed but seemed to encourage.

The missives published in this book are the textual equivalent of the Industrial Workers of the World’s (IWW) Mr. Block cartoons. For those who aren’t aware of Mr. Block, let me quote IWW agitator Walker C. Smith:

Mr. Block is legion. He is representative of that host of slaves who think in terms of their masters. Mr. Block owns nothing, yet he speaks from the standpoint of the millionaire; he is patriotic without patrimony; he is a law-abiding outlaw… [who] licks the hand that smites him and kisses the boot that kicks him… the personification of all that a worker should not be.

In other words, Mr. Block was a satirical character created to call attention to workers and union bosses who identified with the owners and management at the expense of their fellow workers.

Autoworkers Under the Gun makes it very clear how the auto industry’s exorbitant payments to its executives and management combined with a penchant for bankruptcy destroyed it. Calling globalization a “four bit word for sweatshop,” Shotwell points out how CEOs and their co-conspirators control the discussion about the economy by blaming the workers for wanting to earn a living and pension.

As most readers know, the other part of this scenario involves those executives purposely downsizing the corporation by moving jobs offshore. His biting commentary reminds the reader how intentional this entire process is.

Unlike most mainstream reporting on the demise of the auto industry, Shotwell gives the reader the view from the shop floor. It’s not just the harassment from management he describes, he also tells stories about workers using their power to fight back.

After one particular attack on management’s machinations to undermine the workers and their union that drew a strong reaction from the bosses, Shotwell arrived for his shift to find his machine taken apart in a show of solidarity. Without that machine, the line was shut down for the entire shift.

Questioning the value of strikes that are not industry wide because of the International’s cowardice or because of the law, Shotwell urges workers to consider alternatives like occupations and working to rule. The point of the former is to prevent management from closing factories. After all, they can’t close a building if people are inside it.

Working to rule, meanwhile, has multiple effects. It slows down the speedups imposed by management to increase production while also preventing shop closures. In addition, working to rule can create overtime or, even better, the necessity to hire more people. The underlying point of both tactics is to emphasize that it is the workers who run the factory, not the CEOs and their minions.

It was more than a year ago that thousands of Wisconsin workers and supporters occupied the Capitol building in the city of Madison. The reason for the occupation was to try and prevent the anti-worker governor and legislature from passing legislation that would end collective bargaining for all state employees except firefighters and state police, end dues check-off from paychecks, and force unions to re-certify every year.

Under the guise of solving a budget crisis (that was created by giving mammoth tax breaks to corporations and the wealthy in Wisconsin), this bill was forced through the legislature despite the protests. Nonetheless, the protests were a welcome reaction to the never-ending attacks on working people in the United States.

Naturally, a few books have been published about this event, now known as the Wisconsin Uprising. Of those texts that wrote favorably, most have done a fairly decent job of describing the flow of the protests, the workers culture that was celebrated, and the intense feeling of solidarity felt by the participants.

Not all have done as good of a job analyzing why the protests failed and what they mean for the future of workers’ movements in the United States.

There is one entry; however, that does broach both of these subjects with some depth. Titled Wisconsin Uprising, this book, edited by labor writer Michael Yates, provides a genuinely left analysis. The collection of essays is divided into two main sections. One discusses the protests, their background and their organization and the other discusses the future of workplace organizing in the wake of the legislation’s success and the concomitant attacks on working people around the world.

The first section takes its subject and looks at the international aspects of the protest (austerity protests in Greece, Britain, etc.), its roots in capitalist crisis, and the lack of resistance experience among protesters. It was this latter element that gave the protesters false hope regarding the role police play, as well as the role unions play.

Indeed, much like the points made in Shotwell’s text, union leadership often concedes benefits, condition, and wages just to keep union dues structure intact and their paychecks coming in. This strategy eventually backfires because it weakens the unions in the eyes of the workers. Seeing this, corporations and governments attack unions, hoping to further weaken their standing in the eyes of members.

Once the union has been defanged, as occurred in Wisconsin after the aforementioned legislation was rammed through in the middle of the night, the rank and file often stop paying dues out of fear or after drawing the conclusion that the union has no power.

Like Shotwell emphasizes in his book, the best response to the attacks on workers and their unions is simple: more actions, more solidarity, and less complacency. The most positive conclusion to be drawn from the Wisconsin uprising is that there is an understanding in the United States that workers not only are being screwed, but that they will fight back.

The narrative here echoes the hope found in other books about the uprising in Wisconsin and the occupy movement that followed. However it tempers that hope with an understanding of what labor is up against in this latest battle with capital. It is an understanding that comes from the years of experience between the collection of contributors and their leftist comprehension of how monopoly capitalism works.

Shotwell explains why Wisconsin happened in a piece discussing concessions when he writes:

The nation that kicked off the struggle for the eight hour day is logging more hours than any modern industrialized nation on earth. Every household needs two wage slaves and every wage slave needs a vehicle to keep them on the treadmill. The turmoil is designed to foil collective action. The degradation of workers is not natural, accidental or unavoidable. It is a plan. Put the jigsaw pieces together and the picture is clear as glass and sharp as pain.

The complementary reason to Shotwell’s concise explanation of neoliberal capital’s plan for the world is that workers ignored the writing on the wall as long as it happened to someone else, while those that were unionized saw themselves as clients of the union when they needed to be fighters in solidarity with those that were the “someone else.”

Check out these books for their analysis, their insight, and their rabble rousing. Then go do some rabble-rousing of your own.

[Rag Blog contributor Ron Jacobs is the author of The Way The Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground. He recently released a collection of essays and musings titled Tripping Through the American Night. His latest novel, The Co-Conspirator’s Tale, is published by Fomite. His first novel, Short Order Frame Up, is published by Mainstay Press. Ron Jacobs can be reached at ronj1955@gmail.com. Find more articles by Ron Jacobs on The Rag Blog.]