Religion and secularism in the public square

Opposing the promotion of religion and religious practices by government is not the same as opposing religious expression…

By Lamar W. Hankins / The Rag Blog / March 13, 2012

Whenever he speaks, it has become common for Republican presidential aspirant Rick Santorum to state that because of the beliefs or actions of various public figures or the society at large, people of faith no longer have a role in the public square.

Santorum has claimed at various times that this was the position of John F. Kennedy, and is the position of President Obama. And he seems to believe that there are others, many others, who want to prevent religious people from having their say about public policy.

A fair and complete reading of what John F. Kennedy said in 1960 cannot possibly lead to such a conclusion. If anything, Barack Obama sometimes has seemed to agree with Santorum on this issue.

With this repeated assertion, Santorum makes what is often called a “straw man” argument. He has set up a false premise so that he can easily knock it down. But this straw man argument has a purpose beyond mere deception: to galvanize the evangelical vote in his favor. And many evangelicals claim that if the government doesn’t promote their brand of Christianity, then they are being denied access to the public square.

To understand the deceit inherent in this argument, we need to understand what is meant by the “public square.” Generally, and quite literally, the public square is an open public space found near the center of a community and used for public gatherings. It may refer also to all areas of public property which may be used for a variety of events, either with or without permission of the government that controls the property — reference the Occupy Movement in the last half year.

In another sense, public square refers to the use of public places for exercising our rights to free speech. Some communities have areas where people hold forth on whatever topic may interest them and the passers-by who linger to listen to what they say.

This activity was likely more prevalent in the days before the media took information to the masses through newspapers, magazines, radio, and television; and now individuals do so by email, Facebook, and tweets. Of course, we have had mail service since the founding of the country, but that was not a way to reach the masses about public policy concerns until the advent of direct-mail political campaigns, which started about 30 years ago.

In some cases, public buildings have been open for public expression, much like the open areas owned in common by the people. But normally, public expression has taken place in these venues only when the governmental authority responsible for their maintenance has allowed them to be used in this way. Otherwise, the buildings are designated for particular uses, rather than any use a member of the public desires.

For instance, a high school gymnasium or a meeting room at a city activity center is not a public forum unless a group or individual pays a fee to use the facility for such a purpose, or the government opens the facility at a specific time for the purpose of having a public forum.

When an area becomes a public place for free speech, the government may not limit what views are expressed there. All views, including religious views, may be expressed, which gets us to the claim that religion is being driven from the public square. Presidential candidate Rick Santorum recently declared that the First Amendment’s guarantee of the free exercise of religion by all Americans “means bringing everybody, people of faith and no faith, into the public square.”

On this I agree completely.

But Santorum went on to claim that presidential candidate and later President John F. Kennedy said that “faith is not allowed in the public square.” I have quoted Kennedy’s 1960 Houston speech in which he discussed this matter in previous columns and have read it many times. Nowhere in that speech did Kennedy say that faith is not allowed in the public square, but in Santorum’s mind, Kennedy’s views would “create a purely secular public square cleansed of all religious wisdom and the voice of religious people of all faiths.”

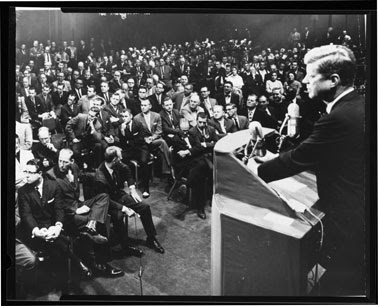

Santorum’s thoughts on this issue are so ridiculous that I address them only to suggest that Santorum has it wrong. Kennedy was not trying to drive religion or religious values from the public square with his 1960 speech to a group of Protestant ministers. He was trying to allay fears among Protestants that, as a Catholic, he would perform presidential duties under orders from the Pope.

Of course, considering Santorum’s membership in Opus Dei, which strictly follows traditional Catholic doctrine, he might seek the Pope’s advice on U.S. policy were he to become President.

But this is not the first time a political figure has distorted the views of Americans to deal with a fictitious issue. In 2006, Barack Obama spoke about religion in public life in a speech at a religious conference in which he accused secularists of asking “believers to leave their religion at the door before entering the public square.” He also equated secularism with a lack of moral values, as though moral values come only from religion.

While I know more religious people than secularists, I have never read or heard a secularist (a non-religious person) who claims that religion and religious ideas are forbidden in the public square. What I have often thought, however, is that if your only argument on a matter of public importance is that God has a position on the issue, you might not have a winning argument.

God’s views are hard to document — something I learned as a pre-ministerial student at a Methodist-related university. Even the “holy texts” leave much room for interpretation and differences of opinion about meaning.

In 2002, a San Marcos city council member explained his vote in favor of a resolution supporting the War in Iraq by quoting Ecclesiastes — “there’s a time for war.” I thought then that the remark was less than shallow and a poor excuse for actual thinking about the matter. Of course, people use “holy texts” frequently to bolster some position or other — against homosexuals, against prostitutes, against money-lending, against slavery; or in favor of slavery, child-beating, war, adulterer-stoning, capital punishment, mass murder, etc.

As to the origin of moral values, perhaps the most universal moral precept is what we usually term The Golden Rule: do unto others as you would have them do unto you. It has ancient origins that have been traced back nearly four millennia to the birth of writing in Egypt (though writing may have begun about the same time in Mesopotamia). But even the Golden Rule has its drawbacks. I certainly would not want a delusional or masochistic person treating me the way she might want to be treated.

What is important to me is that moral values do not depend on religion. Moral values have risen wherever there are people capable of thinking about themselves as distinct entities related to others. In fact, self-reflection may be what distinguishes humans from other species.

In America’s public square, broadly conceived, all people can be participants in the discussion. Perhaps the most inclusive definition of the public square is found in David E. Guinn’s paper written for The Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties:

[The public square is] that forum in which the people discuss, debate, and evaluate public activities with the idea of persuading their compatriots and influencing the state in the development, enactment and enforcement of public policy. It is a forum, by definition, available to all…

The public square is not necessarily a place or a building. Today, forums are developed anywhere ideas can be discussed. In the on-line world, anyone wanting to make a comment can participate in that discussion.

As anyone who has read the Constitution knows, religion is mentioned three times — to guarantee religious freedom, to prohibit government establishment of religion, and to assure that there be no religious test for holding public office. God does not appear in the document except in relation to the date given at the end.

This should not prevent God and religion from entering public discussions, but it does suggest that the government should neither dominate religion, nor religion government. Opposing the promotion of religion and religious practices by government is not the same as opposing religious expression in the public square. Those who equate the two are not being intellectually honest.

According to a 2011 study by the nonprofit, nonpartisan research and education organization Public Religion Research Institute, “Nearly two-thirds (66 percent) of Americans agree that we must maintain a strict separation of church and state.” And 88% of Americans “strongly affirm the principles of religious freedom, religious tolerance, and separation of church and state.” Religious freedom is for everyone.

Contrary to the assertions of people like Rick Santorum and those who use fear to promote their theocratic views, the public square in America is doing fine, open to all ideas, religious as well as secular. And the public square can be used to promote moral values by everyone who has moral values, be they religious or secular.

It is possible to be good without God, even if some people claim otherwise. If you don’t agree, just listen to the values being expressed in the public square and observe the public behaviors represented there. Morality is not exclusive to our religious brethren, nor does being religious assure moral behavior.

[Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, city attorney, is also a columnist for the San Marcos Mercury. This article © Freethought San Marcos, Lamar W. Hankins. Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.]