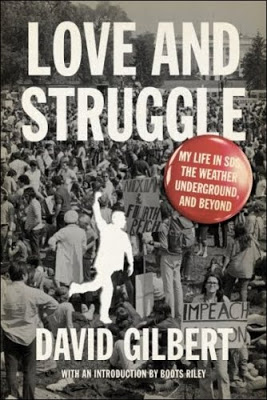

Love and Struggle:

David Gilbert’s memoir helps us

understand our history and the world today

By Rick Ayers / The Rag Blog / March 7, 2012

[Love and Struggle: My Life with SDS, the Weather Underground and Beyond, by David Gilbert. (Oakland, CA: PM Press, December 2011); Paperback, 384 pp, $22.]

This is the third review of David Gilbert’s Love and Struggle published on The Rag Blog. We have run multiple reviews of the same book in the past, when the articles have covered different territory and when we have considered the material to be of special interest to our readers. And we consider this to be a very important book. Also see the Rag Blog reviews of Love and Struggle by Ron Jacobs and Mumia Abu-Jamal.

As I write this, four presidents in Latin America are veterans of revolutionary guerrilla struggles of the 1960’s. Pepe Mujica of Uruguay was a member of the Tupamaros and among those political prisoners who escaped from Punta Carretas Prison in 1971; Mauricio Funes of El Salvador is a member of the Farabundo Marti Liberation Front (FMLN) and his brother was killed fighting in the Salvadoran civil war; Daniel Ortega was a leader of the Sandinista National Liberation Front which fought an 18-year guerrilla war; and Dilma Rousseff of Brazil was a member of the urban guerrilla group National Liberation Command (COLINA) which carried out armed attacks and bank robberies in the late 60’s.

David Gilbert, who is of the same aspirational generation, is living a dramatically contrasting life — presently doing life in a New York prison. His recently released memoir, Love and Struggle, My life in SDS, the Weather Underground and Beyond, opens the door onto a world that mostly exists as some distorted corner of the political imagination of the U.S. in 2012.

But it’s a world and a story that is vivid and compelling — and one worth paying attention to at precisely this moment as a young generation of activists is generating its own stories on Wall Street and beyond.

Like Mujica, Funes, and Rousseff, Gilbert was a militant fighter in the 60s and 70s — but he found himself at war from within what Che Guevara called the “belly of the beast.”

The actor and activist Peter Coyote had this to say about the memoir: “Like many of his contemporaries, David Gilbert gambled his life on a vision of a more just and generous world. His particular bet cost him the last three decades in prison and, whether or not you agree with his youthful decision, you can be the beneficiary of his years of deep thought, reflection, and analysis on the reality we all share. I urge you to read it.”

Written under the appalling conditions of imprisonment in the massive U.S. prison-industrial complex — under the endless dangers, harassments, and frustrations of life in various New York prisons — the existence of this volume is itself an amazing accomplishment.

Gilbert explores crucial issues of the 60’s and today: racism, imperialism, the oppression of women, and the crisis of capitalism. The fact that it is self-critical without being maudlin or self-pitying, the fact that he has crafted a reflective, modest, and ultimately hopeful picture of his life and times, makes Love and Struggle particularly welcome.

We were, as a generation, born into war. After the “good war” to defeat fascism in the 1940’s, the U.S. continued a series of military engagements designed to defeat liberation movements and assure its economic dominance in the world. While most everyone today agrees that the war on Vietnam was at best a mistake and more accurately a genocidal horror, it is curious how the American narrative has twisted even that memory.

Those who seek to draw the U.S. into more military adventures cynically extol the veterans of the war as heroes while leaving a record number of homeless vets to fend for themselves on the streets or to populate the prisons. At the same time, they denigrate the veterans of the resistance. Those who were right, in other words, are never honored in the corporate media — they are erased and disappeared

While David Gilbert represents an extreme of the resistance movement, and while the Brinks robbery which landed him in prison was thoughtless and harmful, Gilbert reminds us that it is essential to confront the many war crimes the U.S. committed in Vietnam — and continues to commit here and around the world — with no consequences.

David’s life sentence does not square with Lt. William Calley’s sentence of three years house arrest for the massacre of 104 Vietnamese civilians at My Lai in 1971 or John McCain’s record of bombing civilians from the air, wanton crimes against humanity; and it does not make sense against the other My Lai’s that occurred on a weekly basis.

Beyond the actions of troops on the ground, a just society would have prepared war crimes trials for top military and political leaders who ordered carpet bombing of civilian areas, the vast deployment of napalm and Agent Orange, the CIA’s “Operation Phoenix” assassination program, the decade-long, “secret” aerial bombardment of Laos, as well as the Cointelpro attacks against African American and Native American activists in the U.S. that resulted in hundreds being killed and imprisoned.

David Gilbert does not ask us to forget the costly human consequences of the 1981 Brinks robbery in which three people were killed and which landed him in prison. But his memoir forces us to encounter and understand much more about the struggles of the 60s and 70s.

Since the release of Sam Greene and Bill Siegel’s film Weather Underground in 2002, there has been a resurgence of interest in those in the U.S. who went from protest to resistance and from resistance to clandestine actions. Five or six “Weather” memoirs have come out in the past decade — each with a different approach or take on the history.

Two excerpts will perhaps capture some of the intensity of his insight and analysis. In discussing the work of the Weather Underground to build a clandestine movement against U.S. international wars, he reminds us of the example of Portugal:

“1974 brought an unanticipated but exhilarating boost to the politics of revolutionary anti-imperialism. On April 25, the dictatorship that had ruled Portugal with an iron hand since 1932 was overthrown. Popular discontent had been central and radicals, including socialists and communists, were major forces in the new constellation of power. The new government soon ceded independence to all of Portugal’s remaining colonies. The series of colonial wars in Africa had drained Portugal’s resources and economy, and that created the conditions for radical internal changes.

We saw the relatively poor imperial nation of Portugal as a possible small-scale model of what could happen to the far more powerful U.S. after a protracted period of economic losses and strains brought on by “two, three, many Vietnams.” The costs of a series of imperial wars could crack open the potential of radical change within the home country.”

And he often counters narrow and stupid characterizations of the 60s and 70s, reminding us of the human faces behind the mythology of the radical movements.

In discussing the death of Teddy Gold, his old friend from Columbia University, he seeks to set the record straight:

“When Teddy and two other comrades were killed in the tragic townhouse explosion, J. Kirkpatrick Sale immediately published a piece in The Nation defining Teddy as the epitome of “guilt politics.” I don’t think Sale ever met Teddy; he certainly didn’t know him. Sale’s rush to judgment probably came from his urgency to discredit any political push toward armed struggle. The “guilt politics” mantra just didn’t fit the deep level of identification we felt with Third World people; and far from feeling guilt, with its condescending sense that we are so much better off than they are, we were responding to their leadership.

The national liberation movements were providing the tangible hope that a better world was possible. Those who caricatured him never saw Teddy on his return from Cuba — the very picture of inspiration, energy, and hope. The word that captures Teddy’s psyche as he built the New York collective was not guilt but exuberance.”

Whether you agree with much that David says or very little, Love and Struggle is a book you won’t soon forget.

[Rick Ayers was co-founder of and lead teacher at the Communication Arts and Sciences small school at Berkeley High School, and is currently Adjunct Professor in Teacher Education at the University of San Francisco. He is author, with his brother William Ayers, of Teaching the Taboo: Courage and Imagination in the Classroom, published by Teachers College Press. He can be reached at rayers@berkeley.edu. Read more articles by Rick Ayers on The Rag Blog.]

The hypocrisy masquerading as righteous indignation of the so called enlightened left leaves a unique stench. The author states that “a just society would have prepared war crimes trials for top military and political leaders who ordered” Operation Phoenix. Which I am sure most of the rag blog readers recognize involved the targeted assassination of VCI during the Vietnam war.

Its almost laughable then, that during the same week this article was published, President Obama’s hand picked AG Eric Holder, held a news conference and provided the legal justification for targeted killings of American citizens. Most media accounts portrayed this as killings of Americans operating in foreign countries. (Only bad evil men would be killed of course). But, with little fanfare, Obama’s handpicked FBI Director, Robert Mueller, in congressional testimony today, said he wasn’t sure if the targeted killings could legally be applied to American citizens on American soil. He stated he would need to “defer that to others in the Department of Justice:.

For some reason, the administrations top crime fighter wasn’t sure if killing Americans in their beds was OK or not. Of course Obama et al will get a pass from the media.

So, my question to the ragsters is easy. When do I start to see your articles calling for war crimes trials for Obama, Holder and Mueller? Bush certainly filled up your pages in years past just for finding a justification for water boarding a handful of people. Onerous as that might have been, they lived to sleep in their beds afterwards. I am not gonna bet much on seeing your expressions of outrage.

– Extremist2TheDHS

Please note:

“Battlefield America” by Richard Raznikov.

http://theragblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/richard-raznikov-battlefield-america.html

Lance: There have been a few instances of acknowledgement of the criminality of the Obama administration. Here is one example. There are many “enlightened left” sites labeling Obama, correctly, a war criminal. It would be helpful if you started citing facts instead of displaying your selective reading and memory so frequently.

Daniel Ortega sold out the women of Nicaragua, acquiescing in one of he most Draconian anti-abortion laws on the planet because he wanted the support of the Catholic bishops of Nicaragua.

Thorne. Thank you. I noted it and corrected myself there.

Richard, I believe you would agree that you have to dig out articles like you referenced. The lame stream media is too busy distracting us with headlines about contraception to deal with Obamas war mongering and co opting liberty. It simply doesn’t fit their narrative. So my argument is valid. The vast majority of sound bite citizens will ave no idea that Obama has doubled down on Bush’s war policies.

-Extremist2TheDHS

If you call searching the Rag Blog using the terms “war criminal Obama” digging, then you are correct. [BTW, a several more examples came up, but the one I cited was the most pointed.]

On your larger point, that the vast majority of Americans “will have no idea that Obama has doubled down on Bush’s war policies,” you are absolutely right. And thank you for making it.