With the US government on a permanent war footing overseas whilst simultaneously cracking down on civil liberties and dissent at home it sometimes seems as if the left wing movements of the 1960s never existed. What do you see as the legacy of groups like Black Mask and the New Left in general?

Ben Morea: Part of the reason I re-emerged [after more than 30 years of anonymity] to talk about what we did back in the 1960s is the fact that things have gotten so bad in the US. It’s at a point where you can’t ignore it, it’s worse than ever.

I figured that I’d start letting people know about our history and then go from there. All I can tell people is that when it looked pretty dismal in the past we took action and it did have an effect. A lot was achieved and yet a few years beforehand no one would have expected that we could take on the behemoth of American capitalism. It’s counter-productive to sit back and say “You can’t do anything.” It’s not my place to tell people exactly what they should do, but there is always some way to respond and take action, just look around.

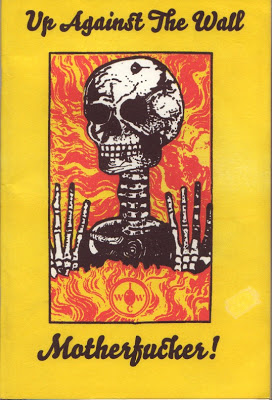

Up Against The Wall Motherfucker! – Interview with Ben Morea

By Ret Marut / March 17, 2008

Morea talks of the 1960s Black Mask and Up Against The Wall Motherfucker! groups and their activities – such as busting into the Pentagon during an anti-war protest, and “assassinating” a famous poet. He also discusses friendships with various characters, including the late Valerie Solanas – who shot Andy Warhol and wrote the SCUM Manifesto.

Morea has a blog at http://e-blast.squarespace.com/

Ben Morea: An Interview

Ben Morea was interviewed by lain McIntyre in 2006.

Tell us about your background and how you came to find yourself involved in the radical scenes of New York during the 1960s.

Ben Morea: I was raised mostly around the Virginia/Maryland area and New York. When I was ten years old my mother remarried and moved to Manhattan. I was basically a ghetto kid and got involved in drug addictions as a teenager spending time in prison. At one point when I was in a prison hospital I started reading and developed an interest in art. When I was released I completely changed my persona. In order to break my addiction I made a complete break from the kids I grew up with and the life I knew.

In the late 1950s I went looking for the beatniks because they seemed to combine social awareness with art. I met the Living Theatre people and was highly influenced by their ideas despite never being theatrically oriented myself. Judith Malina and Julian Beck were anarchists and they were the first people to put a name to the way I was feeling and leaning philosophically.

I also met an Italian-American artist named Aldo Tambellini who was very radical in his thinking and who channelled all of that into his art rather than social activism. He would only hold shows in common areas like churchyards and hallways in order to bring art to the public. He influenced me a lot in seeing that having art in museums was a way of rarefying it and making it a tool of the ruling class.

I’m self educated and continued my pursuit of anarchism and art through reading and correspondence. I became aware of Dada and Surrealism and the radical wing of twentieth century art and sought out anyone who had information about it or who had been involved. I really felt comfortable with the wedding of social thought with aesthetic practice. I corresponded quite a bit with one of the living Dadaists Richard Huelsenbeck who was living in New York, but whom I never met.

At the same time I became friendly with the political wing of the anarchists meeting up with people who had fought in Spain, from the Durutti Brigade and other groups. They were all in their 60s and I was in my 20s.

I was also a practising artist working at my own art and aesthetic. I was mainly painting in an abstract, but naturalistic form as well as doing some sculpture. There was some influence from the American expressionists, but Zen was also an influence.

When did Black Mask come together as a group? How were you organised and who was involved?

Ben: It’s hard to say whether we started in 1965 or 1966, but the magazine definitely started in 1966. Black Mask was really very small. It started off with just a few people. As anarchists, and not very doctrinaire ones, we had no leadership although I was the driving force in the group. Both Ron Hahne and I had already been working together with Aldo doing art shows in public to promote the idea of art as an integral part of everyday life, not an institutionalised thing. Ron and I became close friends and found that we had a more socially polemical view than Aldo in wanting to go closer to the political elements of Dada and Surrealism as well as to the growing unrest in Black America. We wanted to find a place where art and politics could coexist in a radical way. Once we started publishing Black Mask and holding actions other artists and people on a similar wavelength were attracted to what we were doing. I’ve always favoured an organic approach where you don’t have meetings and people just associate informally rather than having a hierarchy and recruiting members.

Over time Ron became less interested in the political sphere and I became more interested in working with the people who were involved in fighting for civil rights and against the Vietnam war. I can honestly say that in both Black Mask and then later The Family we never held a meeting where we consciously sat down to decide our direction or exactly how we would deal with a particular action or situation. It all developed as a very spontaneous, organic outgrowth of whatever we thought was appropriate at the time.

One of Black Mask’s first actions was to shut down the Museum Of Modern Art (MOMA). Tell us about what happened and the group’s approach to direct action in general.

Ben: We felt that art itself, the creative effort, was an obviously worthwhile, valuable and even spiritual experience. The Museum and gallery systern separated art from that living interchange and had nothing to do with the vital, creative urge. Museums weren’t a living house, they were just a repository. We were searching for ways to raise questions about how things were presented and closing down MOMA was just one of them.

The action was a success. We’d announced our plans in advance and they closed the museum in fear of what we might do. A lot of people stopped and talked with us about what we were doing and this action and others attracted radical artists to our fold.

At other times we disrupted exhibitions, galleries and lectures. Most of these actions were just thought up on the spot and a lot of what we did was part of a learning process. Things weren’t completely thought out, but were a way for us to develop an understanding of our place in the ongoing struggle. A lot of political groups would have these big grandiose strategies and plans, but for us the actions were just a way of expressing ourselves and seeing how we could make a dent in society.

In 1966 the group also targeted the Loeb Centre at New York University (NYU). What happened with that action?

Ben: We had a strong sense of humour and of guerrilla theatre. I used to disrupt art lectures at NYU to raise issues other than those that the lecturers wanted to discuss. As a result I was challenged to a debate by some of the academics. I remember that particular event had such a pretentious approach that we had to do something. It was incredibly stratified and only meant for the elite and it seemed like they’d done everything possible to keep it away from the public at large. We handed out loads of leaflets advertising this free event with food and alcohol and they had to block off the streets all around because so many people showed up. We went down to the Bowery and handed out flyers so that all the drunks and street people would show up.

Black Mask clearly drew inspiration not only from the Dadaists, Surrealists and avant-garde movements of the past, but also from the contemporary black insurrections and youth movements of the 1960s. Tell us a little more about these influences and about your ideas and approach to politics and art in general.

Ben: From my perspective and that of the people I worked with we saw a need to change everything from the way we lived to the way we thought to the way we even ate. Total Revolution was our way of saying that we weren’t going to settle for political or cultural change, but that we want it all, we want everything to change. Western society had reached a stalemate and needed a total overhaul. We knew that wasn’t going to happen, but that was our demand, what we were about.

It also meant seeing that you need all types of people involved, not just political activists. Poets and artists are just as important. Revolution comes about as a cumulative effect and part of that is a change in consciousness, a new way of thinking.

How did Black Mask fit into the New York political and arts scenes because it seems as if you went out of your way to ridicule and challenge ideologues of all stripes?

Ben: A lot of political people questioned what we did saying we should only attack society on the political front and that we shouldn’t care about art. However we felt it was best to take action in the place where you were and that as artists these issues were important to us.

Many of the hippies distrusted us and the politicos hated us because they couldn’t control us or understand what we were doing. As for the people in the art world I’m sure most of them thought we were crazy.

Black Mask seems to have issued various challenges to the peace movement in criticising the moderates for their lack of militancy whilst also attacking the Left for its unconditional support of the National Liberation Front (NLF). Many radicals from the 1960s are now somewhat regretful or appear reticent to speak about their support for the North Vietnamese regime.

Ben: We supported the right of the Vietnamese people to resist American invasion, but were not going to support the North Vietnamese government’s own oppressive behaviour. It was a subtle point and most of the left couldn’t understand it. We knew the history of Spain where both the Francoists and Stalinists executed anarchists. We refused to support one side or the other.

I hated the knee jerk reaction of much of the Left who delighted in waving the NLF flag around. We didn’t cheer the killing of American troops who were stuck over there as cannon fodder like some others did.

In a sense we didn’t fit in anywhere and that meant we became a pole of attraction for all those other people who weren’t interested in a dogmatic or pacifistic approach. Much of the later evolution of Black Mask into The Family came about through more and more of these people joining with us and affecting where we were going.

Black Mask and later The Family were some of the first groups to encourage the concept of affinity groups as a way of organising. One Family member famously defined an affinity group as a “street gang with analysis.” How did this approach develop and the use of term come about?

Ben: Although we associated in similar circles with Murray Bookchin our group was always very different because we were very visceral and he was very literate. Murray was keen on using the Spanish term aficionado de vairos to describe these non-hierarchical groupings of people that were happening. We said “Oh my god, can you really imagine Americans calling themselves aficionado de vairos?” (laughter) “Use English, call them affinity groups.”

Tell us about the Black Mask magazine you produced which ran from 1966 to 1968 and spanned ten issues.

Ben: Ron and I mainly put the magazine together, but there was a. wider group who helped produce, print and distribute it. We sold it for a nickel, which wasn’t much money, but we figured if people had to pay for it then they would actually want and read it rather than just take one look and throw it in the trash.

We tended to sell it on the Lower East Side, which was the most fertile ground for us as there were many artists and activists. We occasionally went up town as well although that was more to stir the pot.

Black Mask was one of the first groups to take on countercultural figures like Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg for their timidity, orientation towards religion and status seeking, labelling them at one point “The New Establishment.” From 1967 onwards it seems as if Black Mask moved a lot of its critique away from the arts establishment and towards the growing hippy movement and New Left.

Ben: Although we were critical of them I was close to Allen Ginsberg and became close to Timothy Leary years later. What we were trying to say at that moment was that they were allowing themselves to be used as a safety valve. We wanted to attack the core of society and believed they weren’t doing that. At the time we thought they were being used by the likes of Time and Life magazine although in hindsight Time and Life probably wish they had never covered them, especially Timothy.

We were always trying to shake things up, to push everyone else as well as ourselves. There was always a lot of interchange with all sorts of other radicals and sometimes there was fratricide in that we would strike out at people we otherwise liked just to make a point.

Read all of it here. / LibCom.org

Thanks to Mariann Wizard / The Rag Blog

Even as a “stalinist with a small ‘s'”, I always had a strong admiration and respect for the uncompormising activism of the creative anarchist forces for which Morea was a charismatic voice – and on more than one occasion was glad to be in the company of experienced street tacticians when “the unexpected” (as it inevitably) happened. It is their utter flexibility, and ability to respond rapidly to unfolding events, that recommend the experience of Black Mask and UATW/MF to our understanding.

Anti-elitist to a degree that made SDS look like a fraternity, groups such as the Diggers defined the Sixties for thousands more “street kids” than ever passed through the doors of a meeting.