The credit crunch is morphing from an American-centred financial crisis into a global economic crisis,” says David Bowers of Absolute Strategy Research…

‘Borrowing our way to prosperity’

By Roger Baker / The Rag Blog / August 29, 2008

Damnation! The problems we create when our bankers gamble on maintaining exponential growth on a finite planet. Borrowing our way to prosperity using Chinese loans by pledging our houses as collateral does not seem to be working so well lately. Who would have thought somebody would expect to be paid back before they would lend us some more?

Fortunately all we have to do is print up a ton of money and we can make the problem go away. And with bank bailouts we don’t even need to mess around with all those messy printing presses, do we?

And aren’t you glad this will all have a happy ending with a man like Obama as president?

A Nightmare on Wall Street

Aug 28th 2008Why the credit crunch has lasted so long

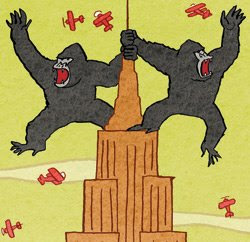

LIKE a Hollywood monster that is impervious to bullets, the credit crisis refuses to lie down and die. The authorities have bombarded it with interest-rate reductions, tax cuts, special liquidity schemes and bank bail-outs, but still the creature lumbers forward, threatening new victims with every step. Global stockmarkets are suffering double-digit losses this year, and credit markets are once again gummed up.For investors who cut their teeth in the 1980s and 1990s, the persistence of the crisis must be a surprise. Prompt action by central banks, after Black Monday in 1987 (when America’s stockmarket fell by almost 23%), or following the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management, a hedge fund, in 1998, suggested it was always worthwhile to “buy on the dips”.

One reason why things are different this time is that there has been a double shock. On top of the decline in house prices and the associated drop in the prices of asset-backed securities, the markets have also had to face a surge in commodity prices. That has constrained central banks from easing monetary policy as much as they might have done, particularly in Britain and the euro zone. Even in America, rates might now perhaps be 1% (as they were in 2003) without the commodity boom.

In addition, the combination of the two shocks has created uncertainty about the direction of monetary and regulatory policy. Will the central banks be forced to “do a Turkey” and adjust their inflation targets upward (implicitly or explicitly) to reflect reality? Alternatively, will they crack down so hard on inflation that they force their economies into recession? And will the price of investment-bank rescues be a harsh new regulatory regime that restricts the scope for future credit (and economic) growth? In the face of all this uncertainty, investors can hardly be blamed for being cautious.

The way that the crisis has centred on the banking industry also explains its duration. Stephen King, an economist at HSBC, points out that the financial crises of the 1990s were also prolonged, from the savings and loan collapses in America through the Swedish banking rescues to the extremes of Japan’s debt deflation. As Mr King says, “if banks are unable or unwilling to lend, monetary policy doesn’t work so well.”

Worse still, bank problems create a feedback loop with the rest of the economy. When banks get into difficulty, they restrict their lending. That in turn makes life more difficult for companies and consumers, causing them to cut their spending and making it harder for them to repay their debts. That forces further caution on the banks.

Recent economic data have highlighted how the gloom is spreading. Neither Germany nor Japan enjoyed a credit boom earlier this decade but both economies are suffering. Business confidence in Germany fell to its lowest level in three years, according to the latest Ifo survey, released on August 26th. “The credit crunch is morphing from an American-centred financial crisis into a global economic crisis,” says David Bowers of Absolute Strategy Research, a consultancy.

Another reason why the crisis is lasting so long stems from the nature of the previous boom. Everyone was borrowing money, from homeowners buying houses they could not afford in the hope of capital gains, to investors buying complex debt products with high yields because of the extra “carry”.

These investors were, directly or indirectly, beholden to the banks. Even when money was borrowed from “the market”, the lenders may well have been hedge funds, conduits or structured-investment vehicles, all of which had themselves borrowed money from banks in the first place. That former wellhead of finance has now run fairly dry.

In turn, that explains the absence of bargain hunters, particularly in the debt markets. Investment-grade debt might look attractive on a five-year view, if all you have to worry about is the risk of default. But most investors in that market have a three- or six-month view; they cannot afford for things to get worse before they get better, in case they are forced into a fire-sale of their assets.

So the markets (and the developed economies) are waiting for a catalyst for recovery. Lower commodity prices helped for a while, and may help further if they encourage central banks to cut rates. Evidence of a bottom in the American housing market may also do the trick. But the crisis seems certain to linger into 2009, and could even make it into the following year. Successful horror movies tend, after all, to have several sequels.

Source / The Economist