Especially on Easter I feel called to preach in a way that reminds us that if we take the text and our tradition seriously, we will be uncomfortable in our imperial society.

By Jim Rigby / The Rag Blog / April 9, 2009

Even in progressive churches that challenge the political and theological orthodoxy, Easter is a day many people want to find comfort in the traditions of Christianity — a special day for putting on one’s sharpest-looking outfit for church and the family gathering. But especially on Easter I feel called to preach in a way that reminds us that if we take the text and our tradition seriously, we will be uncomfortable in our imperial society.

So, I can’t give a traditional Easter sermon, one that makes us comfortable about Christianity, about our nation, about ourselves. On a day when people typically want to take a break from politics, I feel compelled to talk politics.

When I was young and heard about the Nazi holocaust, I didn’t ask the question many of my classmates asked. I didn’t ask “how could Germans do such a thing?” I asked, “how could Christians do such a thing? How did the holocaust happen in the very cradle of the Reformation?” The Lutheran faith was born in those same places that eventually embraced fascism. How is it possible, in our own country, that Christians would go to church every week and not realize there was something deeply evil about slavery? What kind of theology allowed that to happen?

Those Christians said the same creeds we say. They sang many of the same hymns. And yet, their theology did not trigger an alarm when an atrocity was happening. And so I asked myself a question: “Do I have that same theology? Have I been propagandized in a way that I will turn against my brother and sister if they happen to be born in a different country or different religion?”

When I first began in ministry, I was popular. I remember someone once said, “Jim, I’ve never heard anyone say anything bad about you.” At the time, that seemed like a compliment, but is it really? If we really love other people, we need to love them enough to risk offending them. Paul tells us to speak the truth in love. We have to do that for each other. You have to do that for me, and I have to do it for you, because we cannot see ourselves from the outside. We cannot always step outside of ourselves and realize when we’re doing crazy or cruel things.

Most people, inside the church and out, were taught a view of the resurrection that had no ethical implications at all. You were probably taught a theology that’s not immoral, but it’s amoral. In that view, the biblical is about magic tricks. A man is born of a virgin, and then, gets up from his grave. If you believe the story, you’re saved, if you don’t you’re damned. And I want to say, that’s bad theology. When we study the life of Jesus, there are clear ethical implications from the day Jesus says he has come to announce good news for the poor, to the day he tells Peter to love Him by caring for other human beings. The story of Jesus has clear ethical and political implications. And Easter is no exception.

I think Paul is giving us three warning labels for doing theology: The first warning is never let religion talk you into surrendering responsibility for your life. The second warning is never to let theology reduce down to hypothetical truth claims. And finally, Paul warns us never to reduce your worldview down to your own group.

Our text today is a passage in Colossians where Paul tells us, “Because you have been resurrected with Christ, set your heart on higher things.” (Col 3:1) Paul says something very interesting here. He says: “Because you have been resurrected with Christ.” He doesn’t say, “Because Jesus was resurrected.” He’s talking about your life. What kind of a theology tells you to surrender responsibility to Jesus? Jesus didn’t say that. What happens when we do that is that someone else always steps in on Jesus’ behalf.

If you’re Catholic, it may be the church hierarchy; a priest, bishop, or pope may step in to tell you what Jesus wants you to do. So, you’re not surrendering responsibility to Jesus so much as to a cleric. In a Protestant church, we’re cleverer than that. We say, “It’s all about the Bible. Just believe in the Bible.” But then we step in to tell you the right way to interpret the Bible. That’s how we disguise what we are doing. We can pretend that it’s the Bible we care about, but if you’re watching, our interpretation of the book always puts us in power and control over other people. We aren’t trying to control others — it’s just one of those darn things that just keeps happening.

In Colossians, Paul is explaining the Resurrection in a different way than the gospels do. The gospels tell you a story at a level that a child can understand. Even when you’re tired, even when you are afraid, the story gives you a compass. What Paul does is unpack the story and show you how to apply it in particular situations. But you can’t take either version of the story literally.

There are types of theology that completely dis-empower the follower. I would suggest that is what happened in Germany when they told people that obedience was a virtue, no matter what. So the first thing we should know about theology is that it would lead us to our own core. Christ is a symbol of your own soul in its fullness. Christ is your own best self that you can’t always find. Yes, Jesus was a person, but a person who completely died into love, and held nothing back. So in following Christ, we should always discover ourselves as well.

The second warning is not to let theology become a set of theoretical assertions about reality. Notice that Paul now moves to a plea for unity in the early church. The symbols of religion should not point outside our experience to hypothetical beings but should waken us to the real people in our lives. So Christ is a symbol not only of your life, but of the life of your friends and your enemies. Paul tells us to bear with each other, to forgive each other as a way of making love real.

When religion becomes hypothetical, we are disoriented from ourselves and each other. The resurrection didn’t take place when a body got up. That would be a theoretical historical claim. The resurrection took place when the disciples could see Christ in each other. Believing that Jesus got up from the grave does not mean that one has experienced the risen Christ. That we find in the eyes of each other.

There is a hidden life in us all. A radiant being, that permeates every plant, animal, and person that you will ever meet. Christ is a symbol of that hidden life in us all. To be a Christian does not mean to join the Christian sect, it means to be irradiated by that one life. It means to live out of that life and for that life.

The third “warning label” is not to reduce your allegiance to any one group. Paul says in Colossians as in Galatians, “in Christ there is neither Greek nor Hebrew, neither Jew or Gentile, neither barbarian or Scythian, neither slave or citizen. There is only Christ, who is all in all.”

When we hear our leaders say that they will do whatever is in the best interest of America no matter what, or when we hear Christians say that people are saved through Christ alone, we should hear and recoil from the same rhetoric that leads to a holocaust. The words are not purified because they come through our lips. Whenever we put sectarian brackets around our ethics, then we have no ethics. When I am ethical only to those within my brackets, I am unethical to anyone outside them. When I only serve America, and you have the bad judgment to be born on the other side of that boundary, guess who pays for my arrogance?

Paul is talking about a universal humanity into which we become members. He is talking about the common body of humankind. If you look at the text, it seems clear to me that the salvation that’s being talked about is not just joining the Christian church. We are being called to the common body of humankind beyond race, gender, or religion.

What good does it do to take up the Christian label, and then serve the selfish needs of any one group? Two thousand years is enough to know that sectarian Christianity doesn’t lead to peace. But what if we loved universally the way Jesus did? What if we saw, neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female?

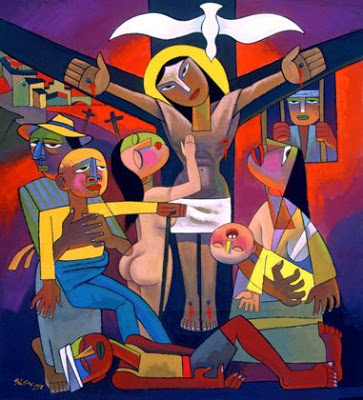

This is the ethical content of Easter. If I think that Christians are better than Jewish people, then the resurrection hasn’t fully happened for me yet. If I think the rich are better than the poor, the Resurrection hasn’t fully happened for me. If I think my group is superior to other groups just because I was born in it, the resurrection has not yet happened in my life.

When we awaken to our common life, something happens to our fear. Our greatest fear is no longer that someone will hurt us, but that we might harm another. Our only fear is of losing the universal love that Christ has given us. So I need not fear that someone will rob me of my life. If I am true to the virtues of patience, kindness, love — the things that Paul lists there — there is nothing on earth that can rob me of that basic, core energy that early Christians called “eternal life.”

And that is why, even though it’s Easter, I’m not going to say that the resurrection is when Jesus got up from the grave. Or that, if you believe in Jesus’ resurrection, then your body will get up too someday. That’s a religion for children. We all start out as children and that’s fine. But if our faith does not grow, then when we are afraid our immature religion will cause us to hurt other people, our immature religion will cause us to reject those who are different, our immature religion will be capable of taking advantage, enslaving, or even killing other people.

That kind of immature, cruel Christianity is a mockery of the One who died and rose again in a small band of Easter people. To be Easter people means to live out of a radical solidarity with our whole human family. To be an Easter people means to have a radical hope that can look at our dangers and unblinkingly affirm that love is stronger than any empire, stronger than any weapon. You know the Easter has happened when, for human betterment, you are willing to face death itself.

[Jim Rigby is pastor of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Austin. This March his sermons are about the Biblical roots of activism. Jim Rigby is also an activist for universal human rights. He can be reached at jrigby0000@aol.com.]

Thanks to Robert Jensen / The Rag Blog

Dynamite sermon – may it reach open ears and willing hearts in people of all creeds, and those who hold to no creed at all.