“One late night in late April of this year, Alan Pogue was severely beaten when he tried to save a woman’s life on a street corner in east Austin. The woman. . . was being pounded by two others. Alan — the noted Austin photojournalist, social activist and frequent contributor to these pages — pulled the two women away from their victim but was sucker punched [by a man he hadn’t seen]. . .”

I wrote those words in The Rag Blog last November, introducing an article Alan Pogue wrote for us about that incident — where he risked his life to save another. Alan, was the staff photographer for The Rag in late Sixties Austin, and for a time lived in his darkroom there. [The Rag, our inspiration, was an underground newspaper, now something of a legend in these parts.]

Alan Pogue has written a remarkable article for The Texas Observer about that harrowing night at Chicon and Rosewood in east Austin. He also recounts his personal history with and his philosophy about the use of violence – from being beaten up as a kid and serving as a medic in Vietnam to a series of incidents in recent times where he has turned to his knowledge of self-defense to help himself and others.

That Observer article, My History of Violence, appears in full below, preceded by some further reflections Alan has written for The Rag Blog.

Thorne Dreyer / The Rag Blog / February 27, 2009

Remembering Kitty Genovese, and buying a gun.

In March of 1964 Winston Moseley stabbed Kitty Genovese on the street in Queens, New York… I vividly remember the article on this crime and that no one helped. I never want to be like those 38 people who would not help.

By Alan Pogue / The Rag Blog / February 27, 2009

The Texas Observer asked me to write a first person account about being jumped while helping a woman in distress at Chicon and Rosewood in Austin. Here is some background on my attacker. He was 25 years old and has been in and out of detention since he was 12. His aggravated assault on me was his third conviction. His father has four felony convictions. I’m told his family does not want him around. He had been out of prison only for a few months when he attacked me. He and his friends were using and selling crack. One may assume he has mental problems.

At the trial his lawyer did his best but there was little doubt about the facts of the case. My attacker showed no remorse or even that he cared at all about what was happening at the trial. Now he is in prison where I doubt anything good will be done for him. On the other hand he is a clear danger and needs to be off of the streets.

The drug bazaar at 12th and Chicon has been there since I came to Austin in 1968. The drug dealers there keep to themselves and their customers. There are some people there who clearly have mental problems. Also there are runaways. Some are prostituting themselves for drugs. Since this is all very obvious one wonders why no concerted effort is made to address the problems. There are plenty of churches nearby but they only do occasional and superficial forays to 12th and Chicon. Much of the action has moved east down 13th street. The drug dealers usually wear something red to indicate they are with the Bloods, or are Blood wannabes. There are other hot spots in north and southeast Austin. The Capitol is another story.

In March of 1964 Winston Moseley stabbed Kitty Genovese on the street in Queens, New York. Thirty eight people heard her screams but no one helped. Moseley went away but then came back and stabbed Genovese again, killing her. I vividly remember the article on this crime and that no one helped. I never want to be like those 38 people who would not help. Moseley is still in prison and he has shown no remorse. He escaped and committed a brutal rape before he was caught again.

But if you do stop to render aid you better be prepared for the worst. Besides not calling 911 before I got out of my car I failed to look around carefully for others who might be involved. Sometimes situations like this are set up to trap people who might help. Stopping to help with a flat tire could be a life threatening situation. That was not the case this time but the result was the same. In the past I have been able to handle attackers that I saw coming.

This time my attention was fixed in front of me, bad. Reflecting on what happened I now know that my attacker had another friend in his car. Had I overcome my attacker I might have had to deal with the other man and the two women. As it is I am fortunate not to have lost the sight in my right eye. As bad as I was hurt, at least I was not shot or stabbed.

But the ghost of Kitty Genovese is still with me. If I come upon another person who is in danger of being raped and/or killed I will help. Since my incident many people have stopped me to relate equally horrible stories about what happened to them. Just a month ago a couple was brutally beaten by four men at 4th and Colorado in Austin. Two people who stopped were also beaten.

So, thinking about all this, I did some research on pistols and came up with the Taurus “Judge” .45/.410. It is a five shot revolver that fires either .45 Colt bullets or .410 shotgun shells. The medium sized shot (like little BBs) .410 shell throws a very wide pattern, about 36″ at eight feet. This is a much wider circle than a regular shotgun throws. So with medium to small shot it would not be lethal unless the attacker insisted on getting very close. “00” buck shot is lethal, as well as are slugs and the regular .45 Colt bullet.

Of course one may not use any kind of gun unless actually under immediate threat of death or serious harm. As I was. But once you are out of your home or car you may not legally have a handgun unless you also have a license to carry a concealed handgun. I went to the considerable effort to obtain one. The backgound check took 120 days. I know they had a lot of files to go through in my case but there is no felony there so I got my permit. I had to take the 12 hours of instruction, pass the firing range and written tests, and pay for that course and the license. I got my senior citizen discount and paid $70 for the license and the full $120 for the course.

I suppose some people are horrified that I did this. I ask them to seriously consider what they would do if they came across someone who would be killed in a minute or so if they did nothing. Screaming does not count toward helping in the case I envision. The two women who were beating Tracey did not stop until I got very close to them. The fellow with the tire tool would not be deterred by verbal threats. He would not be deterred by pepper spray/mace. I did save Tracey’s life but it almost cost me mine. One of the doctors in the emergency room asked me if in the future I would stop again. I looked at her through my one good eye and promised that I would.

Don’t worry, I am not going all vigilante on you like Jody Foster in “The Brave One,” in which an NPRish woman gets beaten and then goes out of her way to shoot people. The drug dealers at 12th and Chicon have not bothered me and I am not going to bother them. As the Observer story relates I have been in some very dangerous confrontations and have not used any more force than was absolutely necessary.

Pacifism in the political arena is a valid method of social change.

Not stopping to help someone who is being beaten is not legally criminal negligence. Certainly there is no law that says one must risk life and limb for someone else. One may stop and render aid but that does not include taking a punch for someone.

Not responding to a murderous attack is suicide. Refusing to be ready is very ostrich like.

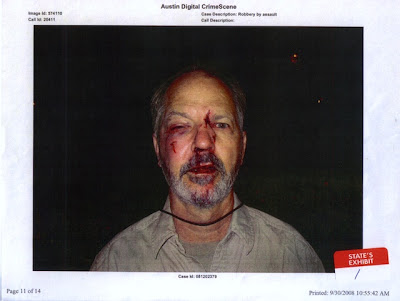

One of the two APD officers took this of me at the scene. They took five pics but the frontal one tells it all. I think seeing it helps people to understand the gravity of my injuries, how vicious the attack was. It was “Exhibit #1” — gruesome, but helpful to understanding my situation. Words can only explain so much and that is why I am a photographer. — Alan Pogue

My History of Violence

By Alan Pogue / February 20, 2009

It was Tuesday night, and I was unable to sleep. I decided to go pick up a book—Can Humanity Change?—a dialogue between Indian philosopher J. Krishnamurti and Buddhist scholars, from my darkroom studio on East Martin Luther King Jr. Street in Austin.

I was driving there when I saw two women beating another woman in the street. I steered straight at them, thinking the attackers would back off as I approached, but they kept kicking and beating their victim, who was curled up into the smallest ball she could make of herself. They were hitting her so furiously that I didn’t feel I had time to call 9-1-1, so I jumped out of my car, intending to break up the fight.

The women finally looked up, angry at the interruption, and sprang at me, throwing wild punches. That gave me an opening to shove them away from the woman on the ground, who slowly got up and began dusting herself off. That’s when I was hit twice in the back of my head, shocking me and turning my reflexes to mush.

I managed to turn around and face my attacker, and saw an African-American man in his mid-20s wearing knee-length shorts. I could see his left hand coming up to hit me again, but I was unable to jump back or raise my arms to deflect the blow. He hit me across the right side of my face with a metal object, then for good measure hit me three more times, as though he were working a speed bag. The pain from the blows nauseated me, and I turned away. One of the women took my wallet.

Someone from the nearby apartments must have called the police, because the three suddenly disappeared, leaving me stunned but still standing. Their first victim was sitting on the curb. With my mind on autopilot, I got back into my car and continued to my darkroom, where I could see in the mirror there that my right eye was swollen nearly shut, there was an inch-long gash over my left eye, and two of my front teeth were cracked.

I picked up the book and my laptop and drove back down Chicon Street toward home. Police and emergency vehicles had gathered at Rosewood and Chicon, so I stopped to talk with the woman I’d tried to help. Her name was Tracey, and she thanked me. Plenty of cars had driven by, she said, and some of them honked, but no one else had stopped.

The EMTs took my vital signs, looked into my eyes, checked my reflexes and asked a series of simple questions to determine whether my mind was functioning properly. I explained that I lived only a few blocks away. They reluctantly let me go. Knowing how awful I looked, I called my wife to warn her.

When I got home she took me to St. David’s hospital, where the doctor who stitched me up told me about a man who’d been brought in the night before. He’d stopped to help a woman with a flat tire, only to be beaten and robbed.

The psychological fallout has been complex. For weeks I was edgy. At night I dreamt of being attacked. Realizing that I had failed to watch my back, I became hypervigilant. Driving down Chicon felt like walking trails in Vietnam in 1968. Instead of watching for tripwires and punji pits, I began peering down alleys and between parked cars. An old high-school buddy delivered a 12-gauge “home defense” shotgun to my bedside, and I admit it gave me some degree of comfort.

Still, the old saw that “a conservative is a liberal who’s been mugged” hasn’t turned out to be true in my case. Getting hit in the face with a tire tool simply highlights the necessity of being able to defend oneself in an occasionally savage environment. Bad air, worse water, rare jobs and inequitable health care are their own forms of social violence, but as threats go they don’t carry the immediacy of a knife at the throat, a gun barrel in the ribs, or an iron bar to the face. The political right often seems unable to address social pathology without resorting to quasi-fascism, and the left wing sometimes appears almost programmatically incapable of defending itself.

What’s a self-protecting person of humanitarian instincts to do? If I’m philosophically opposed to employing potentially lethal physical force in self-defense, then isn’t it hypocritical of me to ask the police to apply that force on my behalf? Physical violence may not be the best way to solve a problem, but if I’m confronted by someone who intends to kill me, loaning them my copy of Can Humanity Change? isn’t likely to be the most effective defense.

My personal history of violence began when I got punched in the nose in the first grade. My father asked me how it happened, explained that I’d be meeting other bullies at school, and taught me how to box so I’d be prepared to take care of myself. There’s usually a bully in every class, and I changed schools often. I took judo lessons at the YMCA.

There was no fighting at St. Edward’s High School in Austin, but W.B. Ray High School in Corpus Christi was rougher. Two upperclassmen there singled me out for harassment, but after I bested them in boxing matches, no one else bothered me.

Attending the University of St. Thomas, in Houston, I finally had a chance to study shotokan karate. My instructor, Sensei Richardson, introduced me to aikido techniques as well. In San Francisco I was able to use those aikido moves to save a man from a beating by deflecting, but not hurting, his attacker.

In 1966 I received my draft notice and said goodbye to California. We practiced hand-to-hand combat in basic training, but my first real fight for my life took place in the latrine at Fort Carson, Colo. A soldier with a knife had me cornered at the end of a long row of sinks. Fortunately, I was able to dodge his attempts to stab me. The military police took care of him after that. In all my previous fights, I’d never had to worry that my opponent might kill me if I faltered. My boyhood was over.

In Vietnam, at different times, I carried an M-14 rifle, an M-16 rifle, a .45-caliber machine-gun, and a .45-caliber pistol. I almost always carried hand grenades. My chaplain had me carry his weapons as well as my own so no newspaper photographer could snap a picture of the armed man of God. The machine gun and pistol were his, the big sissy. The M-16 rifle was mine, even though, as a medic, I never used it. I managed to give away all but one of my ammunition clips so I could carry more bandages. I knew we shouldn’t be there, and I harbored no fascination with fully automatic weapons.

I’d grown up in Corpus Christi, close to Kingsville and “uncle” Mike Gallagher, my fifth cousin. Uncle Mike, at 21, had been the youngest man ever to be made a foreman at the King Ranch, but he was in his late 50s when I first met him. He used a straight razor to shave. He trimmed his thick fingernails with a fine Italian switchblade and filed them with a heavy triangle file. He was very kind and very tough. He never married and had no children of his own, so he “adopted” me and two other boys, David and Ernesto, took us to roundups, bought us baseball gear, and taught us how to ride and rope.

He also taught me how to use guns, so my association with firearms is a positive one, and inextricably entwined with my memory of him.

Uncle Mike had me out shooting cans with a .22 when I was barely old enough to hold a rifle.

Uncle Mike gave me a .410-gauge shotgun for my 10th Christmas and took me deer hunting on the King Ranch that same year. He handed me a Winchester .30-.30, lever-action rifle that I had never fired and told me to hold the butt of the gun firmly to my shoulder because it kicked so hard. Don’t press your cheek to the stock when you’re sighting, or it will rub a burn on your face, he told me. Aim right behind the deer’s shoulder.

With that sage advice taken, I shot my first deer.

My father had given me a Remington repeating, bolt-action .22 rifle when I was 9, and he took me hunting for dove, duck and quail, but he didn’t care for deer hunting. Only years later did I understand his reasons: He was proud that I could shoot better with my little .410 than he could with his 16-gauge Browning with its gold trigger.

My father’s father drove train for the Southern Pacific and the Katy. When he died, I inherited his pocket watch and the pistol he carried to ward off train robbers: a nickel-plated, Colt .44/.40.

Those who grow up without any functional or familial relationship to guns may associate them solely with crime and war. They’re not likely to understand, never mind share, the passion that many people—even nonviolent people—have for gun ownership.

Back in the 1970s, I lived in a small, windowless room in the University YWCA on the drag in Austin. Late one night, someone tried to get into my room. I knew it was no one who belonged in the building since I was the only person who lived there. The incident bothered me enough that I purchased a small 9 mm pistol to keep on the bed in my little cul de sac. One day I got a call from a sweet reader of The Rag, a long-defunct alternative paper, saying that an aggressive heroin dealer was downstairs and would I please photograph him. I went down and took his picture. He charged at me with a small crowbar. I ran toward Les Amis Café, and when I got to the outside seating I picked up a metal chair and threatened to hit him with it. I asked the café patrons to call the police, but they all just sat there transfixed. The heroin dealer finally turned and ran off. I published his photo in The Rag and gave a copy to the police. I carried my pistol until he was arrested.

Another time, I was walking down West 22nd Street around 9 p.m. when I saw a man trying to rape a young woman. I got him off of her, but then he attacked me. My martial arts training allowed me to subdue him even though he was wild on drugs and seemed not to feel any pain. A friend walked by and called the police.

Back in the Y late one evening, I heard the sound of a hammer striking metal. I put my 9 mm in my back pocket and looked out into the hallway. A young man, maybe 15, was attacking a vending machine. He pulled a pistol and pointed it at me. I could have shot him, but I did not. The glance I got of his gun made me think it was only a starter pistol, not a lethal weapon. We had a standoff. In the end, I was not going to shoot anyone over robbing a Coke machine, so I let him pass. I called the police, and an officer came out and took my report. He spotted the 9 mm in my back pocket and berated me for not having shot “the little punk.” In the hallway I found a book with a girl’s name in it. She was a client at the Women’s Center, and from there we learned the name of her boyfriend, the Coke robber.

The “little punk” is still alive because he encountered me and not the police. They would argue that my kind of restraint would get them killed; I’d say they’re too ready to use maximum force.

That encounter at the Y made me realize I’d better augment my 9 mm with nonlethal pepper spray and handcuffs so I’d have more options. One afternoon I was chatting with friends inside Les Amis when a distraught young man burst through the front entrance with a beer bottle in his hand. He rushed onto the wait-stand, broke off the neck of the bottle, and started screaming at the waitresses and cooks, waving the broken beer bottle at them. I approached so he couldn’t see me and grabbed him, pinning his arms to his sides, and threw him to the floor. He dropped the bottle to catch himself and then bolted out the door. Everyone was surprised mild-mannered Alan had done this. Surprised but happy.

Time passed. I lost the handcuffs, and the pepper spray turned stale. The 9 mm stayed locked in a filing cabinet. There have been other incidents, but nothing on the order of what happened to me last April 29. After thinking about the fellow who hit me in the back of the head I’ve come to the conclusion that if I’m going to help people in distress, then I better get some more pepper spray and another type of pistol—one I’m willing to use on a human. There is a pistol on the market that fires .410 shotgun shells, as well as .45 caliber bullets of the same diameter.

I’m thinking about using the .410 shells. A small amount of birdshot would hardly be lethal, but it would be loud, it would generate a huge muzzle flash, and it would hurt. It would be a convincing deterrent.

Some would argue that this arrangement won’t have the stopping power a “real” bullet would exert on the worst-case scenario: a 300-pound homicidal maniac on drugs. Maybe so, but I’m more worried about being able to keep multiple attackers at bay—a situation in which a mere taser would be inadequate. Not killing anyone is as much a priority as not getting myself—or an innocent victim—killed. Until I have to deal with a sniper, a shot pistol will be good enough for me.

Paying attention to your surroundings is the first line of defense. Avoidance is best. Running is good. If I ever again have to save someone from being raped or beaten, I promise to call 911 first, use my pepper spray, and perhaps, as a last resort, deploy my .45/.410.

In addition to psychological trauma, I also now have $38,000 in medical bills to deal with. My present battle is with the insurance company. Tracey has left Austin and is receiving counseling. My attacker is in prison. Tracey’s attackers are at large.

A word of caution. Anyone who owns any kind of firearm must keep it under control. If it is at home, it must be locked up in such a way that no unauthorized persons can unlock it.

When I was a boy, I kept my .22 rifle and my .410 shotgun in my closet. Children were not shooting children in those days. I didn’t own a bicycle lock, either, because no one was stealing bicycles where I lived. No one worried about their children going “trick or treating.” Those days are gone. I wish we had them back. Until they return, I’m relying on more than wishes.

[Alan Pogue has photographed for social justice organizations since 1968. He studied martial arts intensively at John Blankenship’s Cha Yon Ryu and Jo Birdsong’s Aikido of Austin. He apologizes to them for his recent lapse in attention.]

Source / The Texas Observer

Your article brings forward some important considerations in the debate over the right to keep and bear arms.

I’m progressive and I own guns. If the Dems insist on trying to outlaw them they will loose the rural vote.

Up in my mountain home town, almost everyone owns a gun, shootings are very very rare. Being acquainted with them instills respect. We have bar fights, no one ever pulls a gun.

As far as I can recall the last shooting here was in the 1960’s

This guy always seems to end up in the middle of a violent confrontation. I’ve never met anyone in my 65 years, who isn’t a cop, who has had to choose so often, whether to shoot someone or not. Is he for real? I doubt it.

Go ahead and doubt that Alan is real. I’ve known him for over 50 years. When he says something you can take it to the bank. Alan is as real as they get.

The point that I feel is missing from this otherwise excellent and on-point essay is that those who possess the skills and knowledge about how to defend one’s self have a responsibility to share that knowledge with those who don’t have it. Our goal should be to help empower people to defend themselves, so that they do not need “saving.”

Thank you for taking the time to write out your experiences, and to share them. I was attacked about 6 months ago by a neighbor. He beat my car with a heavy iron tool and threatened to kill me. It was sudden and violent while I was backing up. I had been asked to inform them first if we decided to sell our property and we thought we were being good neighbors.

Being attacked changes you. What if my husband had not been with me? The sound of the metal twisting to get loose from the truck hood and then he slammed it in again, making holes in the metal.

We did not call the police. We are terrified of retaliation. We are terrified of our dogs being shot or our home being burned down. We were selling our home, but now we’re selling our ranch.

Unless you’ve personally been attacked and felt the trauma of your life being threatened, you can’t understand. My husband is convinced he’d have killed me if I was alone. I barely made it back to truck when the tool slammed.

Even when I was surrounded by sharks on a pleasure dive (haha), I wasn’t as terrified. We now keep a loaded gun and I’m getting licensed. It’s been on my mind and I know the social implications. My husband inherited several rifles and pistols but we had never used them. We aren’t joining the NRA, but being attacked changed us.

Thank you Allan for being the kind of human who helps.