Zombie-Marxism I:

Why Marxism has failed, and

why Zombie-Marxism cannot die…

(Or, ‘My rocky relationship with Grampa Karl’)

By Alex Knight / The Rag Blog / November 5, 2010

“The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.” — Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1852

“Once again the dead are walking in our midst — ironically, draped in the name of Marx, the man who tried to bury the dead of the nineteenth century.” — Murray Bookchin, Listen, Marxist!, 1969

[First of five.]

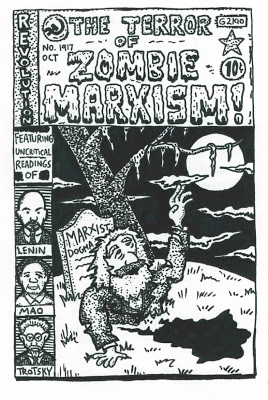

A specter is haunting the Left, the specter of Karl Marx.

In June, my friend Joanna and I presented a workshop at the 2010 U.S. Social Forum, an enormous convergence of progressive social movements from across the United States. The USSF is “more than a conference” — it’s a gathering of movements and thinkers to assess our historic moment of economic and ecological crisis, and generate strategies for moving towards “Another World.”

Our workshop, entitled “The End of Capitalism? At the Crossroads of Crisis and Sustainability,” was packed. A surprising number of people were both intrigued and supportive of our presentation that global capitalism is in a deep crisis because it faces ecological and social limits to growth, from peak oil to popular resistance around the world.

Participants eagerly discussed the proposal that the U.S. is approaching a crossroads with two paths out: one through neo-fascist attempts to restore the myth of the “American Dream” with attacks on Muslims, immigrants, and other marginalized groups; the other, a path of realizing and deepening the core values of freedom, democracy, justice, sustainability, and love.

Despite the lively audience, I knew that somewhere lurking in that cramped, overheated classroom was the unquestionable presence of Zombie-Marxism (1). And I knew it was only a matter of time until it showed itself and hungrily charged at our fresh anti-capitalist analysis in the name of Karl Marx’s high authority on the subject.

It happened during the question and answer period. A visibly agitated member of one of the dozens of small Marxist sectarian groups swarming these sorts of gatherings raised his hand to speak. I hesitated to call on him. I knew he wasn’t going to ask a question, but instead intended to speechify, to roll out a pre-rehearsed statement from his Party line.

I called on others first, but his hand stayed in the air, sweat permeating his brow. Perhaps by mistake or perhaps from a feeling of guilt I gave him the nod to release what was incessantly welling up in his throat.

“I don’t agree with this stuff about ecological limits to growth. Marx wrote in Capital that the system faces crisis because of fundamental cycles of stagnation that cause the falling rate of profit…”

With the resurrection of Marx’s ancient wisdom, a dangerous infection was released into the discussion. Clear, rational thought, based on evaluating current circumstances and real-life issues in all their fluid complexities and contradictions, was threatened by an antiquated and stagnant dogma that single-mindedly sees all situations as excuses to reproduce that dogma in the minds of the young and vital.

Marx didn’t articulate his ideas because they appeared true in his time and place. No. The ideas are true because Marx said them. Such is the logic. If I didn’t act fast, the workshop could surrender the search for truth — to the search for brains.

I would have to cut this guy off and call on someone else. I knew better than to try to respond to his “question” — it would only tighten his grip on decades of certainty and derail the real conversation. Unfortunately, there is no way to slay a zombie. Regardless of the accuracy or firepower in your logic, zombie ideas will just keep coming. The only way out of an encounter with the undead is to escape.

I motioned my hand to signal “enough” and tried to raise my voice over his. “Thank you. OK, THANK you! Yes. Marx was a very smart dude. OK, next?”

Karl Marx was without a doubt one of the greatest European philosophers of the 19th century. In a context of rapid industrialization and growing inequality between rich and poor, Marx pinpointed capitalism as the source of this misery and spelled out his theory of historical materialism, which endures today as deeply relevant for understanding human society. He emphasized that capitalism arose from certain economic and social conditions, and therefore it will inevitably be made obsolete by a new way of life.

For me, what makes Marx’s work so powerful is that he told a compelling story about humanity and our purpose. It was a big-picture narrative of economy and society, oppression and liberation, set on a global stage. Marx constructed a new way of understanding the world — a new worldview — which gave meaning and direction to those disenchanted with the dominant capitalist belief system.

And in crafting this world-view, Marx happened to do a pretty good job wielding the tools of philosophy, political economy, and science, aiming to deconstruct how capitalism functions and disclose its contradictions, so that we might overcome it and create a better future.

Brilliant ideas flowed from this effort, including his analysis of class inequality, the concepts of “base” and “superstructure,” and the liberating theory of “alienated labor.” Marx also showed that the inner workings of capital live off economic growth, and if this growth is limited, crisis will ensue and throw the entire social order into jeopardy. For all these reasons, Marxist politics — the Marxist story — remains popular and relevant today.

But due to serious errors and ambiguities in Marx’s analysis, Marxism has failed to provide an accessible, coherent, and accurate theoretical framework to free the world of capitalist tyranny.

I believe Marx’s foremost error was his propagation of the older philosopher Hegel’s linear march of history. This theory characterizes human society as constantly evolving to higher stages of development, such that each successive epoch is supposedly more “ideal” or “rational” than what came before.

Marx’s carrying forward this deterministic narrative into the anti-capitalist struggle created the confusion that capitalism, although terrible, is a necessary “advance” that will create the conditions for a free society by the “development of productive forces.” This mistaken conception often put Marx, and his uncritical descendants, on the wrong side of history — arguing that in order to achieve the ideal of socialism or communism, countries had to follow the Western European model of becoming capitalist first.

Hegel’s framework of linear progression blinded Marx to non-European, feminist, and ecological critiques of capital’s violent conquest of the world. Without this knowledge, Marx charted a flawed strategy for radical social change that missed the core of what human freedom is all about.

Instead of vocally, unambiguously opposing European colonialism and the displacement of small farmers from their land, Marx construed the proletarianization of the world as a matter of capitalism “producing its own grave-diggers.” Focusing narrowly on the economic “misery” of capitalism and upholding the proletariat as the agent of history, Marx simplified the aims of the anti-capitalist project to a matter of the working class seizing state power to “increase the total of productive forces as rapidly as possible” (Marx-Engels Reader, 490).

This mechanical focus on the hardships of workers led Marx to overlook the many other ways that capitalism threatens life on this planet, and therefore also the resistance coming from those outside his framework: peasants, indigenous cultures, women, youth, queer and trans people, students and intellectuals, immigrants, people of color, artists, and more.

Perhaps most urgently for our moment of climate meltdown, Marx’s view of capitalism as an “advance” blinded him to the ecological destruction that capitalism reaps on our planet, from deforestation to the extinction of species and so much more. Preoccupied with the “development of productive forces,” Marx predicted that communism would come about due to capitalism placing “fetters” on economic growth.

Growth itself was perceived as inherently good, and the rational proletariat would advance it further than capital ever could. Following this logic to its conclusion, Marx praised industrialization as creating the material conditions for the “scientific domination of natural agencies.”

Afflicted with these blindspots, the Marxist narrative was defenseless against repeated manipulations, and mutated into ideological cover for “Socialist” and “Communist” tyrants who have been chief enemies of human liberation. Where Marx’s doctrine didn’t fit the reality of social struggle, as in Russia, China, and every other country that has experienced a “Marxist” revolution, his disciples attempted to transcend reality in order to fit Marx’s doctrine, instead of transcending Marx’s ideas in order to explain reality. The results have been nothing short of nightmarish.

A zombie idea is an idea that has been demonstrably proven false by reality, which has expired in its usefulness, but which continues to reproduce itself by preying on real-live hopes and fears. A zombie idea cannot adapt to new conditions, it only decays. It lacks moral purpose, but will continue to lumber on, propelled by an insatiable hunger, for as long as it can find unfortunate victims.

Sadly, disturbingly, much of Marxist thought today finds itself in such a state. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the monstrosity of “actually existing” Marxism spectacularly failed to bury capitalism. Quite the contrary, it was shocked to find itself swept into the “dustbin of history.”

Proven wrong, this dogma hasn’t stayed dead. Now a mockery of the living philosophy Marxism once was (and for some still is), Zombie-Marxism has continued to weigh heavily on the collective mind of the Left, for the simple reason that we haven’t turned a critical eye to Karl Marx’s body of work itself.

This essay is not meant to be an attack on any particular Marxist, or even on sectarian groups as a species of organization, but rather on a mindset, which uncritically carries forward Marx’s ideas into present circumstances where they no longer fit. Too often, Marx is invoked as an authority on subjects about which he was totally silent.

When Marx did make a statement related to a current issue, it is viewed as confirmation of his wisdom, rather than being evaluated for the relative clarity or obscurity which it brings to our understanding of capitalism and revolutionary practice today.

We need to carry out an autopsy on the old man. There is much to be gained from reading Marx. But when we look to him for all the answers we transform him into a prophet and transform ourselves into a mindless herd. One hundred and fifty years after Marx’s major writings, it is beyond time to ask ourselves: What did Marx get right?, What did he get wrong?, and Why has Marxism failed in practice?

Finally, how can we integrate Marx’s brilliance alongside the insights of many other necessary thinkers, to create a common-sense radical analysis, based not on ideological blueprints of the past, but on our lived conditions in 21st century late capitalism?

I was once infected with Zombie-Marxist ideas myself. I overcame this infection and freed my mind of such undead ideas, so I know it can be done. Of course, I am not the first, nor will I be the last, to raise these questions and attempt a critique of Marx.

For example, in this essay I will draw from the feminist critique of Silvia Federici, the anti-Eurocentric critiques of Russell Means and Kwame Turé, the democratic critique of Murray Bookchin, the anti-statist critiques of Mikhail Bakunin and Emma Goldman, the anti-dogmatic critique of Cornelius Castoriadis, and others.

I offer my own perspective on the Marxist tradition in the hope that others find it useful, and to spark conversation on the need to constantly reexamine our assumptions. Marx himself wrote:

The social revolution of the nineteenth century cannot draw its poetry from the past, but only from the future. It cannot begin with itself before it has stripped off all superstition in regard to the past. (M-ER, 597).

In this era of capitalist crisis, when the entire system threatens to implode, new challenges, and new opportunities, are springing to life. To be relevant to our own century requires shedding the dead superstitions of the past, and facing the future with critical consciousness.

In this essay, I will first recount how I became a follower of “Grampa Karl,” and why I was eventually disillusioned. In the two following sections I will lay out my critique of Marx, limited to what I see as Marx’s five most enduring contributions and his five most debilitating mistakes.

In the remaining parts of the essay I will explain how these theoretical failures led to “actually existing” Marxism — a monstrous dogma which dominated the revolutionary left for a century, and still perpetuates itself as an undead ideology even after mortifying two decades ago.

Finally I will attempt to rescue Marx from the zombies haunting his legacy and situate him in what I call a common-sense radical perspective of living anti-capitalist politics, incorporating newer theoretical developments such as “de-growth,” “reproductive labor,” and “transformative justice.”

My Encounter with Grampa Karl

When I was 18, I read the book Fast Food Nation by Eric Schlosser. The book famously declares “there’s shit in the meat.” Fast Food Nation exposes how factory farms, which produce the vast majority of meat for U.S. consumption, are hell-holes where unsanitary and unsafe practices not only carry out unspeakable animal cruelty, not only endanger and exploit their workers (who are mostly undocumented immigrants), but also pump out enormous quantities of excrement-laden and potentially dangerous meat, which has even killed children with E.coli. And this is to say nothing about the “normal” health effects of ingesting fast food.

The fast food industry is also directly responsible for the clear-cutting of the Amazon rainforest, as huge areas of the world’s most diverse ecosystem are burned down and replaced with ranches raising cattle for Americans’ burgers.

As Schlosser documents, the meat industry is well aware of its socially and ecologically destructive practices, but persists in them for the simple and undeniable reason of maximizing profit. The ongoing disaster has nothing to do with evil or immoral people — the system itself is responsible. Capitalism is feeding us shit and we’re “lovin’ it.”

Facing this truth was too much for my teenage apathy to withstand. My dispassionate ignorance of the world — cultivated by years of television and video games — was suddenly shattered on the grim rocks of reality. As my worldview lay in jagged pieces, I found myself overwhelmed with questions: “Is capitalism killing our planet?” “Why doesn’t anyone know about this?” “If they know, why don’t they ever talk about it?” “Is it wrong to think this way?” “Am I a Communist for asking these questions?”

I sank below waves of uncertainty and anguish. I thrashed about for any explanation of how this terrible reality could make sense. I clamored to know what I could do about it. Drowning in questions, I longed for answers.

Karl Marx presented me with the first solid ideas I could stand on. I read “Alienated Labor” and it gave me a name for the anguish I was experiencing. My hatred for my job did not mean there was something wrong with me, but that I was responding correctly to an alienating and exploitative situation. I wasn’t wrong; the system was wrong.

Feeling validated by the old man, I rapidly developed a strong affinity for his teachings. I read The Communist Manifesto, The Civil War in France, even the Grundrisse. Although the language was thick and foreign, I slowly waded through because my efforts were occasionally rewarded with profound nuggets of insight into my own world. I discovered a long and complex history of Marxist anti-capitalism.

I felt as though I had been mentally rescued. I had found an ideological home, from which I could launch criticisms of the capitalist system and encounter others who desired revolution. Marx was our guide, my guide. His story of class struggle gave me meaning and purpose, which is what I had been seeking.

In mainstream American society, Karl Marx is like an estranged grandfather who no one brings up in polite conversation. A long time ago there was a bitter falling out over politics and he stopped being invited to family functions — all the better because he wouldn’t be caught dead at those “bourgeois” ceremonies.

If the subject of Grampa Karl ever does come up, it’s usually in the context of a ghost story meant to frighten and silence unpatriotic sentiments. For example, Glenn Beck says Marx is controlling our president and destroying the country. On the other hand, Grampa Karl does get some favorable mentions in the university, where the facade of liberal education is more important than any minor disturbance that the introduction of students to Marx’s obscure rantings is likely to produce.

When I became a follower of Grampa Karl, I knew I was distancing myself from the mainstream. If people realized I was consorting with that rabble-rouser they might have thought I was crazy or stupid, or both. I had no problem with that. Rather, I had such contempt for the dominant culture as it exists, that I relished the identity of outsider and rebel.

Moreover, the old man had promised me it was only a matter of time before capitalism collapsed due to its internal contradictions. Time was on our side. I cherished my secret Marxist hope and laughed behind the back of bourgeois society.

But as time went on, Marx’s warts began to show. First, I noticed his almost-total silence on issues of ecology. Being motivated largely by my concern for capitalism’s apocalyptic approach to life on this planet, I strained to find even the slightest clues of environmental consciousness in Marx’s writings. Instead, I was confronted with the faulty notion of a linear development of history, with liberation equated with human domination of nature.

It became increasingly apparent that Marx didn’t have all the answers for me. His analysis was trapped in another century, when industrialization still seemed like a good idea to people.

Nevertheless, I was not ready to abandon my political home just because I had such doubts. On the contrary, I clung all the more desperately to my mentor, seeking to prove him right and his critics, perhaps even myself, wrong.

Looking back, I can locate in myself the attitude of one afflicted with Zombie-Marxism. If I didn’t understand what Marx was saying, it was because he was speaking to a higher truth that I couldn’t grasp. If Marx’s ideas were questionable, I hastened to silence the questions. Instead, I sought to dispose of them by returning to Marx’s writings and scouring for quotes or passages, no matter how tangential, which could be used to clobber those who dared to doubt the wisdom of Grampa Karl.

I felt as close to Marx as to a guardian — he had pulled me from confusion and provided me with clarity. Through him, the world made sense. Or at least I thought it did.

My questions didn’t ebb. I became disturbed by the company Marx was keeping. Leninists, Stalinists, Trotskyists, Maoists, and more, all swarming around him and treating his every word as gospel. Worse, they seemed to spend more energy feuding with each other than building the kind of movement we need to overturn capitalism.

I attended the 2006 Left Forum in New York City and despaired at seeing the horde of Marxist sectarian grouplets denouncing one another over petty ideological questions that had been irrelevant decades ago. Were these people engaged in the same project that Marx had given me?

My disappointment grew, so that when the anarchist critique finally reached me, I was ready to listen. Although it was plainly apparent to me that people like Lenin and Stalin had entirely distorted the liberatory potential in Marx and created something horrifying, the anarchists pointed to the errors of Marx’s ideology and method which paved the way for those distortions.

No matter how smart someone is, they are bound to make mistakes, so labeling yourself an “ist” of someone’s name is to engage in the worship of an individual, which can only detour you from trusting your own feelings and thoughts. How could someone know better than you what is hurting you and what you need to heal?

I saw this cult of personality in Venezuela, where I could not walk down the street, turn on the television, visit the beach or the mountains, without seeing President Chavez’s name or face everywhere. This essay is no place to critique the policies of the Chavez government, which are complex and contain both positive and negative aspects, but the omnipresence of an uncritical Chavismo made me cringe on an emotional level, even if I firmly supported his government against the right-wing U.S.-funded opposition.

I felt betrayed by Marx. He should have known, and stated clearly, that politicians, no matter how progressive, cannot make revolution. It has to come from the bottom — from everyday people organized into social movements — fighting for their liberation. Marx’s “dictatorship of the proletariat” suddenly appeared to me as a pathetic joke. How did he not see how such an absurd idea would be exploited by opportunists? Disillusioned in Venezuela, I read Emma Goldman’s My Disillusionment in Russia and parted ways with Marxism.

Even though Grampa Karl and I are no longer close comrades, Marx continues to influence my politics because there is much to value in his writings. A full recounting of his genius would be too difficult, but I will explore five key contributions of Marx that I believe remain relevant and useful insights today, during capitalism’s global crisis. Then I will follow this with what I see as the five most urgent failures in Marx’s analysis, from which spawned the Zombie-Marxism lurking in our midst today.

Karl Marx was no prophet. But neither can we reject him. We have to go beyond him, and bring him with us (2). I believe it is only on such a basis, with a critical appraisal of Marx, that the Left can become ideologically relevant to today’s rapidly evolving political circumstances.

Here is an outline of the remainder of the essay. Check back soon for more!

*What Marx Got Right

- Class Analysis

- Base and Superstructure

- Alienation of Labor

- Need for Growth, Inevitability of Crisis

- A Counter-Hegemonic World-view

*What Marx Got Wrong

- Linear March of History

- Europe as Liberator

- Mysticism of the Proletariat

- The State

- A Secular Dogma

* Hegemony over the Left

* Zombie-Marxism and its Discontents

* Conclusion: Beyond Marx, But Not Without Him

Footnotes

- The idea of a zombie ideology was transmitted to me from Turbulence magazine and the “zombie-liberalism” they discuss as taking the place of neo-liberalism in the wonderful article “Life in Limbo?”

- This framing comes to me through Ashanti Alston, the “Anarchist Panther,” and his excellent essay “Beyond Nationalism, But Not Without It.”

[Alex Knight is an organizer, teacher, and writer in Philadelphia. He maintains the website endofcapitalism.com and is writing a book called The End of Capitalism. He can be reached at activistalex@gmail.com.]

I look forward to reading the rest of this.

Too much to comment in one Comment; very interesting and definitely has merit insofar as the critique of those who mindlessly cite Marx or anyone else as an authority BUT two quick points:

1. Marx was “blinded” not so much by his analysis of capitalism, but by his own moment in history. The struggle that preoccupied him was the central struggle of his day. The struggles of transgendered people, for example, I hope the old fellow may be excused for not anticipating; these had not yet been made manifest.

2. You seem to be omitting what is possibly Marx’ greatest contribution, as relevant today as it was in 1868: the tool of dialectical analysis. In fact, Marx did not “propagate” Hegel’s straight-line theory of history; this is a gross misunderstanding. Marx “turned Hegel on his head” with his insight into the alternating and mutually propulsive roles of diametrically opposed social forces.

In sum, so far, while the citation of any authority as the summa qua non of social and economic theory is simply stupid and, as you point out, sectarian, please don’t throw out the most valuable analytic tool in the Left’s arsenal with the bathwater.

Karl Marx saw History as a process of change, not static or automatic repetition, yet one capable of being comprehended by human beings.

I, too, look forward to the remainder.

Re Zombie politics in general, are we now seeing the resurgence of zombie conservatism as well??

Nice work, Alex. I really enjoyed reading this.