Margaret Randall, bringing a poet’s voice to her work, gives human dimensions to the heroes of the Cuban revolution.

Listen to the Rag Radio podcast of our interview with Margaret Randall. The author, Alice Embree, joins Thorne Dreyer in this interview. This show originally aired Friday, Oct. 2, 2015, 2-3 p.m. (CT), on KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin. Find all podcasts and more about Rag Radio here.

Listen to the Rag Radio podcast of our interview with Margaret Randall. The author, Alice Embree, joins Thorne Dreyer in this interview. This show originally aired Friday, Oct. 2, 2015, 2-3 p.m. (CT), on KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin. Find all podcasts and more about Rag Radio here.

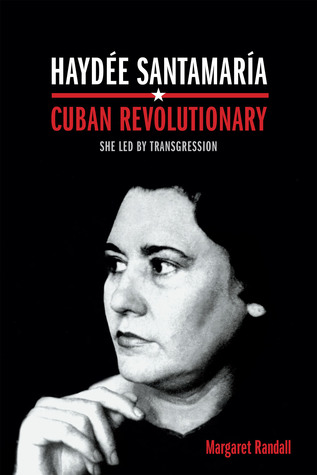

[Haydée Santamarîa, Cuban Revolutionary: She Led by Transgression by Margaret Randall (August 2015: Duke University Press); Paperback; 248 pp; $23.95; Hardcover; 248 pp; $84.95]

Margaret Randall’s newest book is an homage to Cuban revolutionary Haydée Santamaría. It is the story of a woman with a sixth-grade education raised on a provincial sugar plantation. Haydée defied traditional gender roles as she came of age in the early fifties and participated in every aspect of the Cuban struggle.

She joined her brother, Abel, in Havana, and was there at the time of Fulgencio Batista’s coup. In the apartment Haydee and her brother shared, a group of young insurgents gathered to imagine and plan the overthrow of the dictatorship. The group included Haydée’s fiancé and the bearded lawyer Fidel Castro.

In 1953, Haydée was one of two women who took part in the attack on the Moncada garrison.

In 1953, Haydée was one of two women who took part in the attack on the Moncada garrison. Many of the insurgents died, and many were imprisoned. In custody after the attack, the prison guards brought her brother’s eyes and her fiancé’s crushed testicle to her to force her to talk. She famously refused. She carried the loss of her brother and fiancé heavy in her heart until her death in 1980. Margraet Randall quotes Haydée as saying: “I did not die at Moncada, but I left my life there.”

The barracks attack was a military defeat, but the audacity of the action galvanized the Cuban insurgency. A national movement taking its name from the date of the Moncada attack — July 26th — coalesced into a revolutionary force. When Haydée was released from a seven-month sentence, she visited Fidel in prison and smuggled out “History Will Absolve Me.” Fidel had written these remarks for his legal defense. They were published and became both a rallying cry for the insurgency and a blueprint for a different Cuba.

Haydée took on many tasks for the revolution. She built underground organizations, organized support among the Miami exile community, procured weapons and ammunition from the Florida Mafia, and then participated in the armed insurrection in the Sierra Maestra with Fidel, Che, and others. Those military actions were decisive, Batista fled the country, and the revolutionaries made their triumphant return to Havana on January 1, 1959.

Haydée then took on a different revolutionary task — the administration of Cuba’s Casa de las Americas. For two decades she excelled in this role, making Cuba a beacon of revolutionary art, Latin American culture, and international solidarity. Cuban posters, cultural gatherings, and literary prizes had an impact far beyond Cuba’s borders. Haydée’s leadership and vision shaped Casa de las Americas, and Casa’s cultural mission helped break through the blockade that the United States was hell-bent on imposing.

Haydée’s role at Casa de las Americas was internationally renown.

Haydée’s role at Casa was internationally renown. Randall has gathered correspondence and photographs that illustrate the impact she had on artists, musicians, and writers, and the great affection they had for her. Among those quoted are Nobel Laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Chilean artist Roberto Matta, and Chilean singer Isabel Parra. In this cultural work, Haydee embraced diversity and did not conform to conventions of socialist realism. “She Led by Transgression,” is the subtitle of the book. Haydée did so by protecting and amplifying creative voices — those of women, blacks, and queers — that might have been repressed without her advocacy.

Margaret Randall brings a poet’s voice to her work. She captures history, gleans it from correspondence, interviews, and research, but imbues it with an uncommon lyrical quality. The final chapter of Randall’s book is, in fact, an evocative poem inspired by Haydée’s life.

In her book published a year earlier, Che on My Mind, Randall pays tribute to another Cuban hero, painting a portrait of the man — the myth, the vision, the legacy — showing the human dimensions with light dancing off the many facets. The book about Haydée has the same qualities — both history and illumination.

In her book published a year earlier, Che on My Mind, Randall pays tribute to another Cuban hero, painting a portrait of the man — the myth, the vision, the legacy — showing the human dimensions with light dancing off the many facets. The book about Haydée has the same qualities — both history and illumination.

Che was killed in combat and celebrated as a hero. Haydée took her own life in 1980. Randall explores Haydée’s death with compassion. The Cuban revolution could not easily accept her suicide, and Haydée was not mourned as a heroine in the Plaza of the Revolution. With the perspective of time, as well as the understanding of the toll that loss and depression can impose, Randall celebrates Haydee’s life and gives the world another chance to mourn her death.

Both of Randall’s recent books have awakened my memories of Cuba.

Both of Randall’s recent books have awakened my memories of Cuba in 1968. I traveled there in a blockade-busting trip organized by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) before the Venceremos Brigades were organized. I remember my delegation burst into applause as our bus went barreling through a highway toll booth, never slowing down because there were no tolls. I remember that buses cost five cents and “pay” phones were free.

Cuba had eliminated illiteracy and established universal, free healthcare and educational opportunities. There were shortages in grocery stores, limited choices, blocks of soap without commercial wrappers, bins for recycling medicine containers at the pharmacies.

Billboards that once advertised soft drinks had been repainted with revolutionary messages — images of Che Guevara or Camilo Cienfuegos, slogans like “Hasta la Victoria Siempre.” Cuba was an outpost of defiance and solidarity for liberation struggles around the world.

Cubans knew my hometown’s name, not as a hipster haven, but as the city where Charles Whitman shot people from the University of Texas tower. They may have been able to see more clearly than we could where our culture of violence was heading.

We were young and hardly battle-scarred, just on the cutting edge of 1968.

We were young and hardly battle-scarred, just on the cutting edge of 1968 — a year that would be marked by the Tet Offensive, the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the demonstrations at the Chicago Democratic Convention, and student uprisings around the world from Columbia University to France to Mexico to Japan.

We traveled from Cuba on a vegetable freighter to Canada, crossing back into the United States near St. John. I remember returning to North America’s omnipresent advertising — feeling the heavy weight of consumerism descend like ether around us. I remember the feeling that racism was palpable on the streets of New York, visible in a way it had not been in Cuba. And, of course, I remember the FBI visit after the trip, as though I needed a reminder that the State Department said I shouldn’t have traveled to Cuba.

Both of Randall’s recent books make Cuba come alive. These books are well timed with the restoration of diplomatic relations and the easing of travel restrictions. They convey the vibrant history of revolutionary change. They also give human dimensions to the heroes of that revolution, reminding us what they risked, the losses they suffered, and what they were able to achieve.

Read more articles by Alice Embree on The Rag Blog.

[Rag Blog associate editor Alice Embree is co-chair of the Friends of New Journalism and a veteran of SDS, the original Rag, and the Women’s Liberation Movement. Alice is a long-time Austin activist, organizer, and member of the Texas State Employees Union.]

How wonderful to see Haydee Santamaria finally recognized for her immense contributions; I want to read it! Thanks, Alice!

Why does the hardcover edition of

Haydée Santamarîa, Cuban Revolutionary: She Led by Transgression, (August 2015: Duke University Press);

Cost $84.95?

Walter Teague

I suppose you need to ask Duke University. The paperback is affordable.

Walter, our hardcovers are casebound library editions. We expect individual consumers to purchase the paperback, which is $23.95.

Alice clearly gets the poetry in this heartfelt rendering of Haydee’s life, along with affirming the historical times. That Alice brings in her own experience underscores the beauty of Margaret’s biography. Randall’s deeply researched book expresses in clear language the foundation of the Cuban Revolution through the life of a key participant, helping a public not familiar with the facts of the Revolution to understand the urgency of need & Cuba’s creative approaches to equitable social organization.

Thank you for this good review and also the comments. The expensive hardcover edition of the book is mostly for libraries. The paperback is affordable and the digital version even more so.

As a 1st generation Cuban-American it is good to see more literature produced that catches us up on the story of those who brought Castro’s egalitarian dream to fruition. At least for a period.