George, a Ragstaffer and leading force in the Austin left, was found dead in the cold locker of an Austin convenience store in 1967.

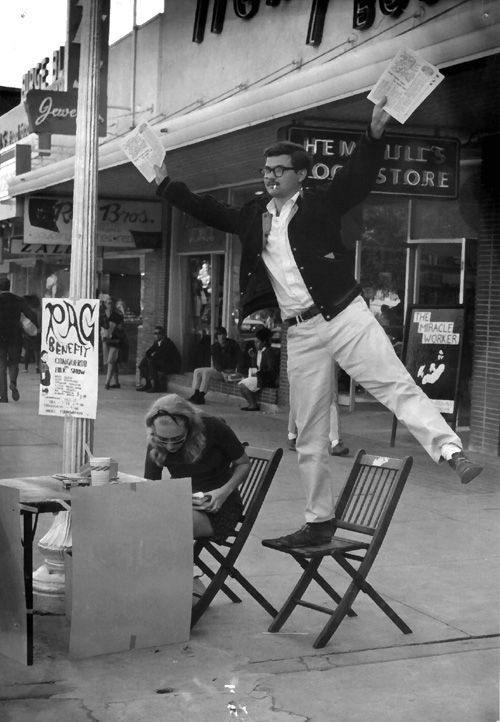

George Vizard, shown selling Austin’s underground newspaper, The Rag, in front of the University Co-op on the Drag across from the UT campus. Seated is his wfe, Mariann Vizard. Photo: October 1966.

Rag Blog associate editor Alice Embree wrote the following article — about the life and murder of original Ragstaffer George Vizard — for a book that will be released this October in conjunction with a 50th Anniversary “Rag Reunion and Public Celebration” of Austin’s historic underground newspaper, The Rag, that published from 1966-1977. The Rag has been reborn into the digital age as The Rag Blog, with many original Ragstaffers involved in the paper’s online resurrection, including George’s widow, Mariann (pictured above), who later changed her last name to “Wizard.”

Rag Blog associate editor Alice Embree wrote the following article — about the life and murder of original Ragstaffer George Vizard — for a book that will be released this October in conjunction with a 50th Anniversary “Rag Reunion and Public Celebration” of Austin’s historic underground newspaper, The Rag, that published from 1966-1977. The Rag has been reborn into the digital age as The Rag Blog, with many original Ragstaffers involved in the paper’s online resurrection, including George’s widow, Mariann (pictured above), who later changed her last name to “Wizard.”

The Rag Reunion (“50 Years and Still Raising Hell”) takes place October 13-16, 2016, in Austin, and will include exhibits, presentations and discussions, parties, a Gentle Thursday reunion, a concert at the iconic Threadgill’s restaurant and music venue, and much more. Learn more about it on our Rag Reunion page. The yet untitled book will include more than 100 articles from the original Rag, accompanied by lots of iconic art and photography, including work by artists Jim Franklin and Gilbert Shelton and photographer Alan Pogue, as well as several contemporary essays reflecting on the history and impact of the paper.

This is the first of several articles, to be published in the Rag book, that The Rag Blog will post over the coming weeks leading up to the October happenings.

When George Vizard was murdered on July 23, 1967, I lost a friend and comrade. George was part of The Rag from the beginning. These words of tribute and remembrance have been written with the help of Mariann Wizard, George’s widow. I hope this corrects a deficit in The Rag’s coverage. The Rag never acknowledged George’s contributions to the Austin left and to the newspaper, and never reported on his death.

George, born in 1943, was raised in San Antonio along with his brother, Austin musician Ed Vizard. He attended San Antonio College before transferring as a junior to UT-Austin in the fall of 1964. In the three and a half years he lived in Austin, he played a major role in the battles for racial justice and free speech, and an end to the war in Vietnam.

Although my parents lived in Austin, I was living on campus in the fall of 1964. I would occasionally join my parents at All Saints Episcopal Church, returning home with them for Sunday dinner. I was surprised to see George there at a church service. He was serving as an acolyte — technically a crucifer — carrying the cross. Much later, I learned he had considered becoming a priest.

Since I knew him from civil rights meetings and demonstrations, my parents invited him to dinner. George was the kind of person your parents wanted you to bring home. He didn’t sit behind a newspaper speaking only when spoken to. He engaged easily with my family. Mariann said he won her mother over when, at the sound of her car in the driveway, he jumped up to help bring in the groceries.

George was serious about politics, but he wasn’t a dour, droning politico.

George was serious about politics — so serious he later joined the Communist Party — but he wasn’t a dour, droning politico. He had a playful side. He sometimes read to audiences from Winnie the Pooh at Ichthus Coffeehouse. When Mary Poppins opened at the Varsity Theatre in the fall of 1964, George and I stole away from the Student Union Chuck Wagon — where members of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) spent countless hours — to see the Disney film. We loved the silliness — the tea party rising up into the air. We came back to the Chuck Wagon serenading our fellow comrades with “A spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down.” Mariann memorialized our duet in a poem that she wrote after George’s death.

George had an easy presence — a comfort in his own skin. It was a good fit for a job running the customer counter at Home Steam Laundry where he worked off and on. The owner liked him so much that he loaned him a suit when George married Mariann in December of 1965. Rev. Bob Breihan married the two of them in the chapel of the Methodist Student Center.

In an iconic photo taken in the fall of 1966, George Vizard is pictured in front of the University Co-op, standing on one leg on a folding chair. His arms extended, he is hawking The Rag, holding copies of the latest issue in both hands. He’s wearing his “whites,” so the photo was taken either before or after his shift at the Austin State Hospital. His wife, Mariann, is seated beside him.

George was listed as “Under Shitworker” — a level beneath Shitworker — in The Rag’s first staff box. In the next issue his name appeared as “Supersalesman.” The second issue carried his account of confrontations with the UT police over whether The Rag could be sold on campus. This argument was carried all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and settled in The Rag’s favor years after George’s death.

George’s political beliefs made him

bolder than most.

George’s political beliefs made him bolder than most. In 1965, he initiated a picket line at Roy’s Lounge (later the punk bar Raul’s) when the bar wouldn’t let George and a black friend in to use the phone. We kept that picket line going for weeks, gathering at the University YMCA/YWCA (the “Y”) at 22nd Street, and walking down Guadalupe to picket at the bar at 27th Street. The demonstration often drew a crowd from nearby fraternities that would jeer and taunt us with racist slurs, aiming ugly sexist insults at the women. George was arrested at one of those Roy’s Lounge demonstrations.

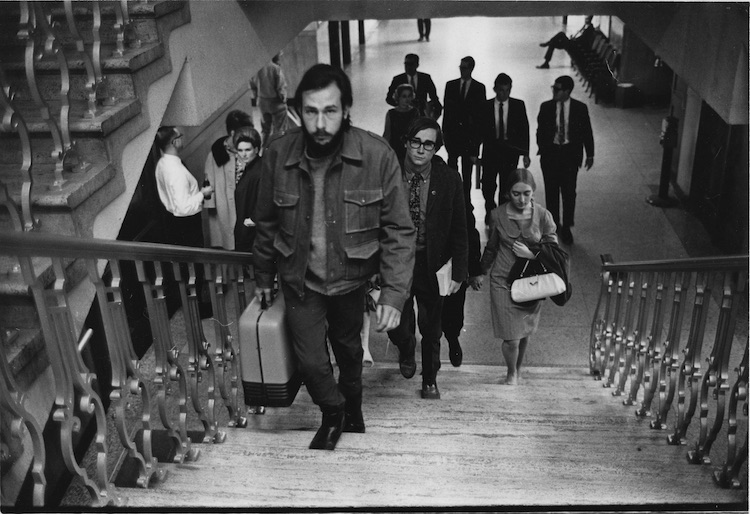

Thorne Dreyer, with projector, David Ledbetter, and Mariann Vizard assist at trial of George Vizard, Travis County Courthouse, Austin, Texas, 1967.

In January of 1967, George was arrested again at an antiwar protest of Secretary of State Dean Rusk. I remember standing at the Capitol doors, my knees shaking, while George — with a firm, fearless voice — told a Department of Public Safety (DPS) trooper we had a constitutional right to hand out the antiwar leaflets in our hands. Mariann and another woman, Mary Mantle, were inside being jostled by the troopers. Mariann recalls George coming to her rescue as a trooper held a baton against her throat. That got George arrested.

A few months later in April, SDS held an antiwar demonstration at the Capitol protesting Vice President Hubert Humphrey. George saw a counterprotester strike Sandra Wilson in the face with a picket sign. He yelled at the police; that led to an arrest several days later. In fact, the Board of Regents as plaintiff obtained an injunction to prohibit the presence of three non-students on campus, declaring that “openly opposing the actions of the United States of America in its foreign policy” is “against the best interests of the University of Texas.”

George was eating breakfast at the Chuck Wagon when police presented him with a warrant for his arrest. Going limp, as was nonviolent practice, he was dragged across the cement and pavement, his back bloodied so badly that he had to be taken to Brackenridge Hospital before being booked.

Lt. Gerding’s response was: ‘Well, Alice, I always told you this sort of thing could be dangerous.’

On July 23, 1967, George Vizard was shot to death in the cold locker of the convenience store where he worked. It was a Sunday. We knew Austin Police Lt. Burt Gerding from his nonstop surveillance, and would sometimes alert him to demonstrations. I called Gerding to tell him George had been murdered. His response was: “Well, Alice, I always told you this sort of thing could be dangerous.” Whether this was the provocative bravado typical of Gerding, or had a darker meaning, I will never know.

On the Sunday we learned of George’s death, there was a community gathering at the “Y.” Mariann did not think a demonstration at the Austin Police Department (APD) was appropriate. As news spread to other cities through the Vietnam Summer network, letters demanding action poured into APD and to local officials. There was no action. Instead, Mariann was subjected to a polygraph, and friends of George were questioned. Law enforcement officers filled the back seats of the funeral service at Weed Corley.

Rev. Bob Breihan, who had married George and Mariann, presided over the funeral at Weed Corley. My mother came with me out of respect for the young man whom she had met. Rev. Breihan, as he had done at the wedding, read from Ecclesiastes 3:

To every thing there is a season,

and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die…

As was discovered much later, the lead homicide investigator concealed evidence that would have led immediately to Robert Zani, a former UT student with right-wing leanings, and a recently fired employee of the convenience store. Zani’s fingerprints were on a loaf of bread and wrappers on the counter, witnesses saw him there that Sunday, and a tip had come in identifying him as a possible suspect who had asked for help robbing the store.

It would be 14 years before Zani was arrested.

It would be 14 years before Zani was arrested after he and his wife Irma had committed several other murders, including, it is believed, of Zani’s mother in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and, in 1979, of a San Antonio realtor whose credit cards Zani was holding when he was taken into custody. When police interviewed Irma Zani in Mexico, she told them that Robert had “killed a guy in Austin… some place around the university.” Sentenced to 99 years in 1981 for George’s death, Zani died in the prison infirmary in 2011.

While Zani was imprisoned, papers belonging to former UT Police Chief Hamilton came to the attention of former Rag staffers. They had been kept at Hamilton’s house and sent to Half Price Books after his death. They revealed that Zani had volunteered to be a “narc” as early as 1964, and that Hamilton had introduced him to contacts at the Texas DPS for assessment. Because DPS records from the era have been destroyed, the question of whether Zani was a police “asset” at the time he murdered George Vizard remains unanswered.

I got on a plane to Santiago, Chile, on August 9th, just two and a half weeks after George’s death. I didn’t return to Austin until December 1969, and was of no great help to Mariann. George’s brother, Ed, accompanied her to the police station to see the evidence box and crime scene photos. But I know this: Mariann and I will be forever connected by the shared bond of knowing and loving George.

Read more articles by Alice Embree on The Rag Blog.

[Rag Blog associate editor Alice Embree was part of the original Ragstaff, as was George Vizard. She typed and wrote for The Rag, Austin’s legendary 60s-70s underground newspaper and was a contributor to Sisterhood is Powerful, a 1970 anthology of writings about women’s liberation. She was a founder of Red River Women’s Press. After receiving her master’s degree from UT-Austin in 1987, she served as a strategic planner for the Texas child support program. She has written for the Texas Observer, is a director of the New Journalism Project, and has been a union member and peace and justice activist in Austin for many decades.]

Alice, thank you so much for writing this. You give me too much credit for your own labor of love! Many, many people loved George, and were positively influenced by his life and courage. I would love to see many of them/you share their memories of him, here, at the upcoming Rag reunion, with their closest friends and especially our children, or wherever/whenever the spirit of peace and justice comes to you.

I was blessed to know George for just over two years, to be his wife for one and a half, and to have the privilege of being his “relict” for what is now, unbelievably, 49. But I never owned him, and never thought myself his sole representative in this world as time goes by. Sister Alice, especially, keeps his memory green, but she is by no means alone. Hundreds of people through the years have told me that knowing George changed their lives; I’m certain I’ve still not met them all.

Regarding the proposed demonstration at the Austin Copshop the evening of George’s death, I would like to say something about that.

In shock from the morning’s hideous news, delivered by an equally shocked Mary and Tom (her then-husband) Mantle, I was taken to their house for the day as Geo’s and my apartment did not seem particularly safe nor desirable. Dick Reavis came to the Mantles’ in the early evening to report that a large group of anti-war activists, having been assembled in Dallas when news of George being murdered reached them, were at the University Y planning to march upon the police station with various “demands” regarding the murder investigation. From what Dick said, many of them — most of whom had actually never met George — were emotionally wrought up and floating a number of ideas for what should be done. Dick expressed that the situation was potentially dangerous, and and Geo’s and my closest friend, Paul Pipkin, also at the Mantles’, concurred.

Knowing at that point NOTHING except that George had died in an apparent robbery of the convenience store (convenience store clerk was then and still is a very hazardous job) and that at least some of Austin’s less-than-finest would be happy to know it, it seemed prudent to allow the cops a chance to find a killer rather than possibly getting a bunch of out-of-towners arrested or worse.

So I went to the Y and calmed the crowd, the first time I ever spoke to a group of people like that, when Alice (altho she doesn’t remember it) first called me “Wizard,” a name that stuck. The crowd respectfully deflated and went home. The “investigation” unfolded much as Al describes.

If I had a nickle for every time I’ve wished I had incited those emotional peaceniks to burn the Cop Shop to the ground and seize State power, well, I guess I might have gotten to be the head of the Secret Police in the ensuing Stalinist provisional government.

But I didn’t, and time keeps on rolling, and Zani and the corrupt homicide cop and Lt. Gerding and a lot of those peaceniks — Chet Briggs comes to mind with much respect — have passed now, too, as have my parents, George’s, and Alice’s, too. I like to think of George posted up by St. Peter’s Gate welcoming newcomers to the afterlife, where all secrets are revealed and only Truth and Love remain. I imagine he has them sorted out pretty well by now.

As another who’s life was altered by knowing him, Il’ll buy into that vision of George.at the gate. And I won’t be surprised if he’s standing on one leg atop a folding chair, freely distributing the latest copy of “Angel’s Free Press”.

I remember your telling us that you didn’t want any political hay made from George’s death. It got scant mention in the Rag after you said that.

Dear Alice,

Thank you so much for this incredible chronicle.

And I thank you too, dear Mariann for your response, adding so much to this wonderful article about George, quien en paz descanse.

I remember Marian saying, tearfully, at the Y, very shortly after George’s death, “I don’t want anybody making any political hay from George’s death!” I assumed this was the reason that The Rag made no mention of it.

George was an awesome person. He was my brother-in-law, and in the very short time we knew him, we (my entire family) adored him. He was funny, charming, intelligent, handsome, and loving. He had deep and passionate convictions. I was 13 years old when he was murdered, going on 14. It remains one of the biggest losses I have ever experienced. I went to the trial of Robert Zani, a very pitiful excuse for a human being if ever there was one. Paul Pipkin and I sat through the tortuous testimony, hearing things that we had not heard before. Paul recently died, and I imagine he and George have a lot of catching up to do. I like to think they are hanging out together.

I worked with George at the Austin State Hospital where we were attendants. He was a great guy to be around and we were good friends. I assumed he was a college student like myself. He had a cool since of humor and I miss him a lot.