Valuable insights into journalism offer a very enjoyable read.

Reading this book has provided me with a unique experience that is both intellectual and emotional, and I think it could be the same for others. I recommend this newspaper reporter’s memoir with considerable enthusiasm, and this review will explain why.

On an intellectual level, I learned a lot of interesting facts and history from the pages of this book. On an emotional level, I became truly excited and even shocked as I read about the author’s work covering the horrors of war and poverty in numerous Asian nations over several decades.

The author’s writing style makes both aspects truly enjoyable — I was neither bored nor disgusted. I confess to being horrified at times, as I was confronting reality, that is, the “truth” in the book’s title.

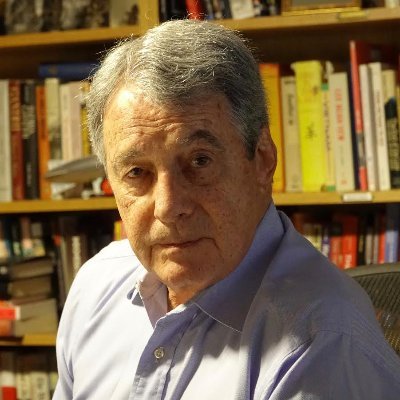

For most of the last half of the twentieth century, Simons (usually accompanied by his wife and children) lived in various Asian countries and covered events there for newspaper readers everywhere. It was his job, and given his devotion to the profession and to his talent, it’s worthy of respect for its high quality — and especially the very intentional honesty.

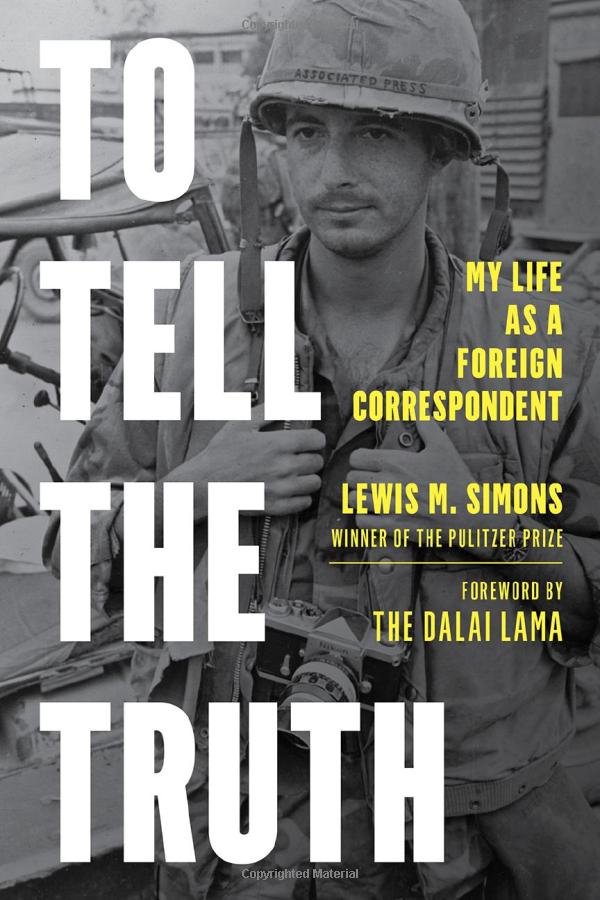

The book’s opening chapter is entitled “Murder in Manila.” The year is 1983. Simons waits for subsequent chapters to share about his many previous years working for the Associated Press (AP) and the Washington Post, but at this point in his career, he is with a less well known news outlet – the San Jose (California) Mercury News.

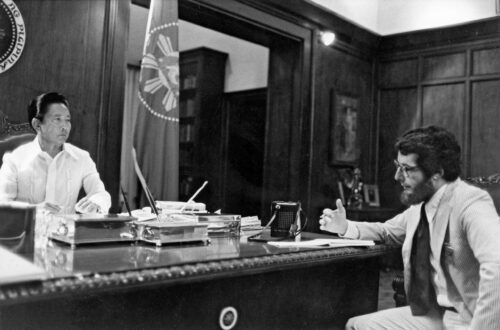

The victim of the murder in the chapter title is Benigno Aquino Jr. and the apparent perpetrator is his political foe, Ferdinand Marcos. Most Americans, due to the habitual trivializing of the news, probably remember Ferdinand’s wife, Imelda Marcos and her numerous pairs of shoes, much more than the meat of the story.

Simons covers how poverty had gripped the Filipino people largely due to the extravagances of the Marcos regime, how Marcos finally was forced out of office into exile, and he touches on the support that the Marcos regime got from U.S. President Ronald Reagan.

This is just one example of how Simons, though not defining himself as a leftist or a liberal, refers to political reality as part of the truth he wants to tell. Donald Trump is mentioned in the book several times, especially when the author points to lies and corruption endemic to autocrats.

Simons and his ‘Mercury News’ colleagues received a Pulitzer Prize for this coverage.

Simons and his Mercury News colleagues received a Pulitzer Prize for this coverage of the crisis in the Philippines. Adding to the honor of the Pulitzer, Simons can also claim prestige by having perhaps the world’s most respected Asian, the Dalai Lama, write a laudatory foreword for the book.

To Tell the Truth recounts Simons’ coverage of news in Vietnam, Cambodia, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Japan, and China, and I’ll mention some of the details later in this review.

AP team at U.S. Army camp in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands, 1967. L-R: Lew Simons, Peter Arnett, John Lengel, and Rick Merron.

First, the required “full disclosure.” Lew Simons was my classmate in 1963-’64 at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. We traveled different paths after graduation. While he was employed by the AP and the Post, I decided to depart from what we called “the establishment press” to join people like Thorne Dreyer of the Austin Rag in the “underground press.”

This is a good moment to use the saying “Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water.” And the context is the Vietnam War. I left the Washington Post in 1967, after being employed there only a few months as a cub reporter, because the newspaper editorially supported the Lyndon Johnson policies in Vietnam and, in its news coverage, belittled the anti-war movement which was already my political “home.” (My story is in my 2018 autobiography, Left, Gay & Green: A Writer’s Life, reviewed in The Rag Blog.

However, in decrying the flaws of the establishment press, I don’t think we ever meant to demean hard-working journalists devoted to the truth who were observing events and people on the ground and gathering facts about the Vietnam War. That’s how we came to learn about the My Lai massacre and more.

Simons’ detailed description of his time in Vietnam is one of the highlights of this book.

Simons’ detailed description of his time in Vietnam is one of the highlights of this book. He attended official briefings, of course, but he also ended up in extremely dangerous situations, such as crawling through tunnels carved by the North Vietnamese Army and/or Viet Cong and on missions where he stood alongside soldiers wounded — and killed — in direct combat.

In Cambodia, Simons witnessed what he called “ritual cannibalism,” after soldiers had killed an allegedly corrupt officer.

“They had shot him in the head,” he begins, adding: “…then excised his heart, liver, lungs, biceps and calves. As Jacques [another reporter] and I looked on, a soldier placed the organs and flesh on a small wood fire. The smell was nauseating,” and the narrative continues to the act of eating.

Describing a shooting incident in Cambodia where a bank guard had blown off the back of a soldier’s head,” Simons wrote: “His brain spilled onto the pavement in a puddle of blood. I’d never seen a human brain before. It looked creamy, almost like a serving of scrambled eggs. How does a normal person react to such horror? Would a normal person faint? Vomit? Scream? Run? What would a normal person do?”

“I took notes. And wrote the story. No longer was I normal,” Simons concluded.

Simons was present for the horrific violence perpetrated by the Suharto regime in Indonesia. By then, he was writing for National Geographic, and I was pleased when he mentioned a movie about the Indonesian conflict, The Year of Living Dangerously, one of my favorite films.

He also was present in China at the time of the Tienanmen Square massacre, yet another dangerous moment in his long career.

There is also a strong narrative that one might find in a history book.

Lurid details are one aspect of this book — and I’m going to quote another one in a while — but there is also a strong narrative that one might find in a history book. I have lived my life — acquiring and retaining a reasonable amount of clarity about world affairs — not being a news junkie but someone who follows local, national, and international news on a daily basis. So I can say with some confidence that I have above average knowledge of important events going on in the world. But as I read, To Tell the Truth, I felt ashamed because of what I did not know. Happily, the shame faded away as I enjoyed the learning experience.

So, let me explain. Do the names Mahathir Mohammed and Lee Kuan Yew mean anything to you? I did not know those names, but each is a major figure in chapters in Lewis Simons’ book. Mahathir Mohammed was the autocratic ruler of Malaysia in the 1980s and Lee Kuan Yew made history over many years from the 1960s to the 1990s by turning Singapore into the modern nation depicted in the entertaining movie Crazy Rich Asians. By reading this book, I learned some details about these historic figures in nations that the media mostly ignore.

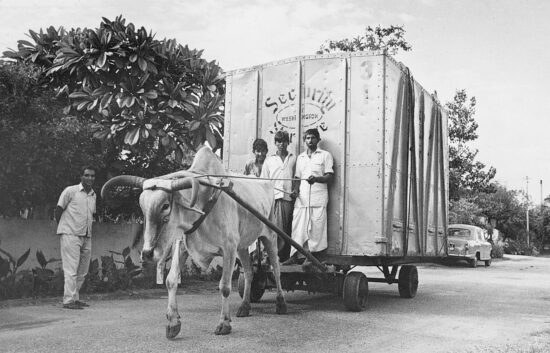

India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh are a trio of nations where Simons spent a good deal of time. Again, I learned a lot. I already knew that when British colonial rule in India came to an end, the territory that the Brits occupied was divided into an independent India (dominated by Hindus) and an independent Pakistan (dominated by Muslims and with east and west sectors).

Until I read this book, I was not aware of the horrific violent conflict that resulted when the Bengali Muslims of East Pakistan declared their independence to create the nation of Bangladesh. Simons uses the word genocide to describe the violence, with a particular focus on the raping of Bengali women by the Muslims of the western sector of Pakistan. He quotes a Pakistani leader to show that this was actual policy, not just bad behavior by soldiers.

Again, to confess my ignorance, until the war in Iraq happened, I was not aware of the angry bitter and violent split between Sunni and Shiite Muslims — and these are not the only factions or sects in the Islamic world!

He declares that religion has been a major reason for violence between peoples.

Earlier in the book, Simons tells the reader about his Jewish heritage and upbringing in New Jersey, but several times as he describes the violence he witnesses, he declares that religion has been a major reason for violence between peoples. Of course, we know this includes not only Muslims and Hindus, but also Jews and Christians and even Buddhists at various times in history, including the present. My classmate’s negative attitude toward religion very much resembles mine, and he provides thoughtful evidence and support.

Perhaps the book’s most vivid and disturbing incident of insane violence due to religion is Simons’ account of the actions of armed men known as Mukti Bhini. They were considered “freedom fighters” as Bangladesh became independent, but they took “barbaric revenge” on members of a non-Muslim minority known as Biharis. Here are a few sentences:

Have you ever seen a human stomp another? Stomp? Smash the heels of his boot into noses and eye sockets, over and over, until the fragile bone crunch and shatter? Have you ever watched deep-red blood and pink intestine spill from a bayonet slash to the stomach? Have you heard the unholy screaming? Have you looked into the maddened, sweating face of a grey-bearded man as he slams the butt of his rifle into the throat of a teen-aged boy splayed on the ground? Over and over again? Have you stood there, close enough to touch either of them, said nothing, while writing in a notebook?

I have.

The way that religion has caused conflict definitely needs to be taught.

It’s traditional for liberals, pressing for separation of church and state, to say that religion should not be taught in schools — especially Christianity as an almost official religion in the United States. I agree with that. But the role of religion in the world — the variety of religions and the way that religion has caused conflict — definitely needs to be taught. Such teaching could help prevent future wars.

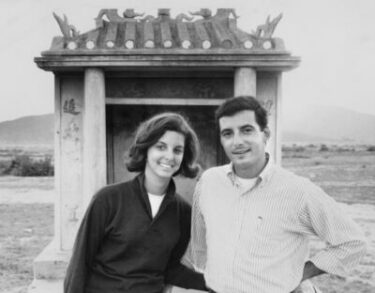

Simons’ wife Carol, also our Columbia J-School classmate, is mentioned in the book, as are their three children. But this is a memoir about Lew’s career and not an autobiography, so many of the personal aspects are missing. It should be clear to the reader, nonetheless, that family is crucial to Lew’s life and that Carol sacrificed a lot of comfort and her own career ambitions to be with him (and worry about him, too). The author rightfully honored her for this and also for finding a way to do her own work as a skilled editor and writer.

Similarly, we get only limited tidbits about food, clothing, music, and scenery. Environmental politics takes a back seat to war and economic issues, just as it did (shamefully) in the underground press of the 1960s.

I feel it’s important to share Lewis Simons’ message about the importance of a free press. He devoted his life to this concept and he’s damn lucky he’s alive to tell the tale, (as he has done for his readers) in these 278 pages.

Referring to Trump’s attack on journalists, and listing more than a dozen dictators who have stifled a free press, Simons offers this paragraph and more:

There are good reasons why journalists are among a dictator’s first targets: A free press serves the governed, not the government. A free press means an informed people. A free press means a free country.

I’d like to offer a personal addendum to this review, appropriate for Rag Blog readers. The variation of journalism that occupied most of my career (and Thorne Dreyer’s career) is what I have termed “advocacy journalism” or “activist journalism,” directly in alliance with the anti-war and anti-racist political movements we adhered to. I even was willing to call my writing “propaganda,” explaining that my purpose was to propagate ideas and information neglected or suppressed by the establishment press. I like to think I was as committed to truth and honesty as Simons was in his work.

I offer strong praise to Lewis M. Simons as a successful rank-and-file reporter committed to truth and who endured danger and often suppressed his own opinion as part of the professional ethic he embraced. I’m glad that in writing this memoir, he did not withhold his opinions. He comes across as a strong advocate for freedom and democracy and a clear opponent of the frightening and dangerous Trumpian Republican Party.

[Allen Young has lived in rural North Central Massachusetts since 1973 and is an active member of several local environmental organizations. Young worked for Liberation News Service in Washington, D.C., and New York City, from 1967 to 1970. He has been an activist-writer in the New Left and gay liberation movements, including numerous items published at The Rag Blog. He is author or editor of 15 books, including his 2018 autobiography, Left, Gay & Green; A Writer’s Life — and a review of this book can be found in the Rag Blog archives.]

An engrossing review of what must be an even more engrossing book. Perusing the book on Amazon, Lewis Simon writes smoothly, with deep accuracy, heart rending depth and heart breaking imagery. Especially his parts about the brutal visual imagery of war, smashing of heads, gushing of blood, and the screaming in pain, he reminds me much of the late Robert Fisk. Like that venerable Middle Eastern correspondent, Simon couldn’t seem to pull himself away from the insanity of wars that he abhorred yet was hopelessly addicted to, at least in the telling thereof. I have often wondered what pulled so many written and photo correspondents to war. Some become quite obsessed with telling about it. It’s wonderful that there are those that do that, wonderful for all the rest of us, for war is clearly an immense insanity that grips our times, as it has for a long time. So a deep thanks to Lewis Simon and all the others.