The experiences of Shelley and D’Emilio differ largely because of their unique backgrounds and life goals.

Two new books, which I just finished reading, merit a wide-ranging readership, so whether you are well-informed about the gay movement, or know little about it, the writers offer some valued insights. Furthermore, you might also have some fun getting to know two very different individuals. The authors, Martha Shelley and John D’Emilio, both in their seventies, have contributed an enormous amount to the gay movement and thus to the transformation of our nation’s politics and culture.

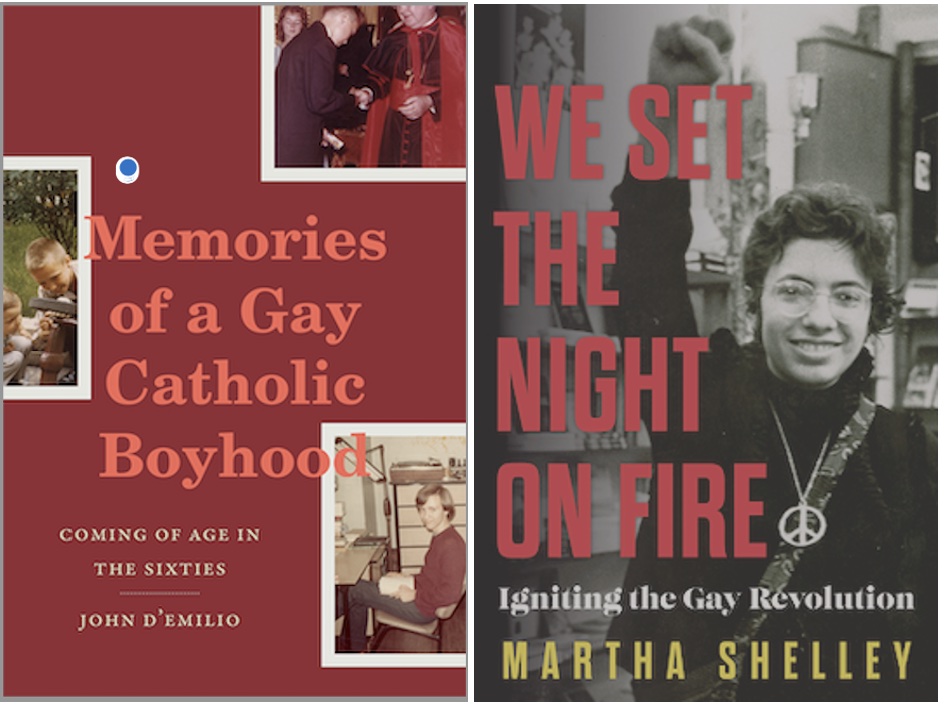

The books are: We Set the Night on Fire: Igniting the Gay Revolution by Martha Shelley and Memories of a Gay Catholic Boyhood: Coming of Age in the Sixties by John D’Emilio. Memoirs, as most readers know, are quite popular, and I want to address that for a minute. I found this on the web: “Since the early 1990s, tens of thousands of memoirs by celebrities and unknown people have been published, sold, and read by millions of American readers. The memoir boom, as the explosion of memoirs on the market has come to be called, has been welcomed, vilified, and dismissed in the popular press.”

I authored a book that is an autobiography, somewhat different from a memoir. My 2018 book is Left, Gay & Green: A Writer’s Life, and a review was published on The Rag Blog.

A memoir offers a limited view featuring just a portion of the writer’s life.

As I understand it, an autobiography provides the reader with a full narrative of the writer’s life, starting with birth and into the present day. A memoir, on the other hand, offers a limited view featuring just a portion of the writer’s life. Of course, the stories of people, real and imagined, are also found in novels, but in memoirs such as these two, the reader is linked to biographical facts including a limited amount of personal intimacy.

When I was striving to have my autobiography published, I found publishers urging me to write a memoir about my work as a pioneering gay activist, but I wanted to tell my full story, so I ended up having to choose self-publication. Shelley and d’Emilio found publishers for their works. Good for them, and for us!

They are not the first gay liberationists to write memoirs. Earlier ones, which I think are excellent, too, are Karla’s Jay’s Tales of the Lavender Menace: A Memoir of Liberation and Mark Segal’s And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality and Liberation.

The experiences of Shelley and D’Emilio differ largely because of their unique backgrounds and life’s goals, though both spent their childhood in NewYork City, both moved away from New York, and both became involved in leftist and gay politics.

Gay historian Jonathan Ned Katz wrote this jacket blurb for D’Emilio’s book:

In this fascinating self-portrait and insightful portrait of his times, a prominent queer historian recalls growing up in the 1950s and ’60s — a smart, pious, conservative, Catholic boy from a working-class Italian family in the Bronx transforms himself into a radical left, openly gay Columbia University student.

The promotional paragraph for Shelley’s book on amazon.com is a good succinct summary:

Martha Shelley didn’t start out in life wanting to become a gay activist, or an activist of any kind. The daughter of Jewish refugees and undocumented immigrants in New York City, she grew up during the Red Scare of the late 1940s and 1950s, was inspired by the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements that followed, and struggled with coming out as a lesbian at a time when being gay made her a criminal. Shelley rose to become a public speaker for the New York chapter of the lesbian rights group the Daughters of Bilitis, organized the first gay march in response to the Stonewall Riots of 1969, and then cofounded the Gay Liberation Front. She coproduced the newspaper Come Out!, worked on the women’s takeover of the RAT Subterranean News, and took a central role in the Lavender Menace action to confront homophobia in the women’s movement. Martha Shelley’s story is a feminist and lesbian document that gives context and adds necessary humanity to the historical record.

I attended many meetings of the New York Gay Liberation Front (GLF) with Martha and she was certainly not one of the quiet attendees. A word that comes to mind is “feisty.” Her writing has a similar feeling. I was personally disappointed that there wasn’t more about GLF, but the truth is that the existence of GLF was limited to about two years and her book covers several decades.

Martha tells stories about lesbian-feminist groups and activities centered in both New York and California.

Martha tells stories about lesbian-feminist groups and activities centered in both New York and California over several decades, while not delving into the latest years and the process of aging. Her page on Wikipedia is informative.

During the early days of our movement, dogmatic radical leftists were uncomfortable with the topic of homosexuality and unwelcoming to our presence on the activist scene as self-declared revolutionaries. These Marxists asked questions such as, “How does your movement relate to the means of production?” Martha’s response was “Marxist, schmarxist, get off our backs,” a line in an article she wrote for the Liberated Guardian. This was an unforgettable put-down of the narrow-minded leftists! Martha certainly provides evidence of her keen awareness of income and wealth inequality.

D’Emilio is a rather studious fellow, with a long career in academia. His education at a Jesuit high school, and then obtaining both a bachelor’s degree and a doctorate from Columbia University, required the kind of discipline and devotion to books that are rare in teenagers — and most of the book is about his teenage years. We don’t find out about his career as teacher and writer, such as how he first discovered Black civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin — subject of D’Emilio’s award-winning book Lost Prophet — and when he learned that Rustin was gay.

The process of fully coming out, reaching self-acceptance, and then being ‘openly gay,’ is explained in detail.

Certainly, D’Emilio deserves all the awards and accolades he obtained. He now enjoys retirement. His Wikipedia page tells the details of his career. Both Shelley and D’Emilio have a political goal as writers, but also share with the reader information about their sexual and romantic involvements. Because gay men have had easy access to casual or furtive sex, as compared to lesbians, those aspects of the book are quite different. D’Emilio’s vocabulary includes cruising, cocks, and ejaculation, and meeting strangers on the streets, in subway cars, and city parks. For Shelley, it’s more about various girlfriends and I don’t think the word “vagina” appears in her book. For both authors, the process of fully coming out, reaching self-acceptance, and then being “openly gay,” is important and explained in detail.

D’Emilio was also quite serious about his Roman Catholic faith, imposed on him like a ton of bricks by his parents. So when, in his teenage years, he started having sex with men, he went to confession. He told the priest there about “impure actions with another man.” Later, he even considers becoming a priest despite all of the illicit sex he’s experienced (and enjoyed). That alone offers insight into the way that so many gay men find their way into the priesthood. (Just to be clear, gay priests apparently had nothing to do with D’Emilio’s own sexual development or experiences.)

D’Emilio is also exceedingly respectful of both his traditional Italian-American family (even though he had to escape their right-wing politics to become a leftist). And this respectfulness extends to the religion, too. I found that baffling. As a secular Jew growing up among heterosexuals, I experienced repression, too, but nothing like what comes from Roman Catholic dogma and clergy.

If he did get angry about Catholic dogma, I didn’t catch that in his book.

As I was reading, I wanted to inquire, “John, don’t you get angry at the repression you suffered because of your religion?” Aside from the anti-homosexual teaching of his church, I wonder about other things. For example, the Christian (including Catholic) dogmatic line that “Jews killed Jesus” was a major factor in anti-Semitism, but D’Emilio does not broach this subject at all. He must have given it thought living in New York and getting to know lots of Jews. If he did get angry about Catholic dogma, I didn’t catch that in his book.

In both books, the authors share many names — of siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins, and friends, and I found myself skimming over some of those sentences. The family experiences and relations are important, but it’s hard to follow. I make this comment knowing that my autobiography is also filled with many dozens of names, perhaps irrelevant to the reader.

In another matter related to names, my book has been faulted for not having an index. It’s a legitimate gripe, and I will say the same thing about these two memoirs that lack an index. An index is an expense for any publisher, but it’s so useful!

Given the rise of Trumpism and its virulent rejection of the gay and lesbian movement — what is now the GLBTQ+ movement — it’s important to look back and understand how this social justice movement evolved through the eyes and actions of pioneers such as Shelly and D’Emilio. Books like these memoirs are a resource for today and for the future. Unlike that line in the famous song, the “Internationale,” there is no “final battle.” We are in an ongoing conflict for justice and freedom.

[Allen Young has lived in rural North Central Massachusetts since 1973 and is an active member of several local environmental organizations. Young worked for Liberation News Service in Washington, D.C., and New York City, from 1967 to 1970. He has been an activist-writer in the New Left and gay liberation movements, including numerous items published at The Rag Blog. He is author or editor of 15 books, including his 2018 autobiography, Left, Gay & Green; A Writer’s Life — and a review of this book can be found in the Rag Blog archives.]