Caribbean Monk Seal Gone for Good

By Jessica Marshall / June 9, 2008

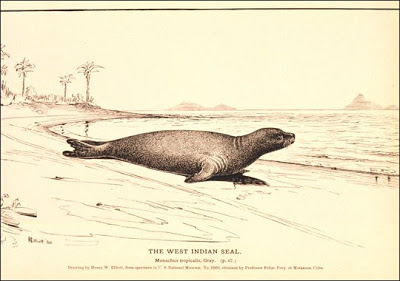

The Caribbean monk seal is officially extinct.

Last seen in 1952 on a small group of reef islands between Jamaica and Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, the seal — covered in brown fur tinged with gray, and with a yellow belly — was easy prey for European settlers in the 1600s and 1700s, who killed it for meat, oil, and to seal the bottoms of boats.

The crew of Columbus’ second voyage was the first to kill the seals. “It’s one of the first mammals that Columbus saw when he discovered this region, and it’s the first one to go extinct,” said Kyle Baker of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association’s Fisheries Service in Saint Petersburg, Fla.

“By the mid 1800s, they were very rare,” Baker said.

The seal was the only subtropical seal native to the Caribbean.

Several seal sightings were reported in the Caribbean between 1952 and the present, but until the 80s and 90s — when people began carrying cameras and cell phones — it was difficult to verify whether those sightings really were Caribbean monk seals.

“Reviewing the data, we’ve identified most of these as hooded seals, which are Arctic species coming down from the northeast,” Baker said. Other sightings have turned out to be bearded seals and harbor seals, but none have been Caribbean monk seals.

With better information, “we decided it was time to do the status review [under the Endangered Species Act] and to come to the conclusion, unfortunately, that the species is now gone,” Baker said.

Two other species of monk seal remain: the Hawaiian monk seal and the Mediterranean monk seal, both also endangered with only 1,200 and 500 seals remaining, respectively.

The Hawaiian monk seal suffers from different threats than hunting by humans, according to Bud Antonelis, who heads the Protected Species Division at NOAA Fisheries Service in Honolulu, Hawaii. The Hawaiian seals face threats from habitat loss, food limitation, marine debris and shark predation.

“We expect in the next couple of years, the numbers will be below 1,000,” Antonelis said. The population is declining by about 4 percent a year.

Removing marine debris and sharks that threaten unweaned pups is part of the recovery plan, Antonelis said. Some seals have been brought into captivity and fed to treat malnourishment, then released.

In many places, the seal’s habitat could be restored, Antonelis said. Erosion has been the major cause of habitat loss. “There’s a lot of conservation work that remains to be done,” he added.

“While the loss of the Careibbean monk seal is extremely disappointing, it serves as a lesson for us to pay attention to the resources that are still here and to do everything we can so that the same problem doesn’t happen to them,” Antonelis said. “I don’t think it’s too late for the Hawaiian monk seal.”

Source. / Discovery News

The Rag Blog