After 60 Years, Arabs in Israel Are Outsiders

By Ethan Bronner / May 7, 2008

JERUSALEM — As Israel toasts its 60th anniversary in the coming weeks, rejoicing in Jewish national rebirth and democratic values, the Arabs who make up 20 percent of its citizens will not be celebrating. Better off and better integrated than ever in their history, freer than a vast majority of other Arabs, Israel’s 1.3 million Arab citizens are still far less well off than Israeli Jews and feel increasingly unwanted.

On Thursday, which is Independence Day, thousands will gather in their former villages to protest what they have come to call the “nakba,” or catastrophe, meaning Israel’s birth. For most Israelis, Jewish identity is central to the nation, the reason they are proud to live here, the link they feel with history. But Israeli Arabs, including the most successfully integrated ones, say a new identity must be found for the country’s long-term survival.

“I am not a Jew,” protested Eman Kassem-Sliman, an Arab radio journalist with impeccable Hebrew, whose children attend a predominantly Jewish school in Jerusalem. “How can I belong to a Jewish state? If they define this as a Jewish state, they deny that I am here.”

The clash between the cherished heritage of the majority and the hopes of the minority is more than friction. Even more today than in the huge half-century festivities a decade ago, the left and the right increasingly see Israeli Arabs as one of the central challenges for Israel’s future — one intractably bound to the search for an overall settlement between Jews and Arabs. Jews fear ultimately losing the demographic battle to Arabs, both in Israel and in the larger territory it controls.

Most say that while an end to its Jewish identify means an end to Israel, equally, failure to instill in Arab citizens a sense of belonging is dangerous as Arabs promote the idea that, 60 years or no 60 years, Israel is a passing phenomenon.

“I want to convince the Jewish people that having a Jewish state is bad for them,” said Abir Kopty, an advocate for Israeli Arabs.

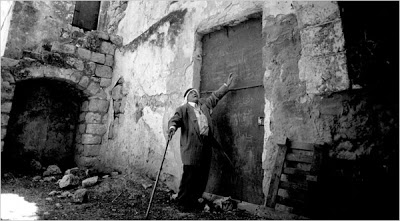

Land is an especially sore point. Across Israel, especially in the north, are the remains of dozens of partly unused Palestinian villages, scars on the landscape from the conflict that gave birth to the country in 1948.

Yet some original inhabitants and their descendants, all Israeli Arab citizens, live in packed towns and villages, often next to the old villages, and are barred from resettling them while Jewish communities around them are urged to expand.

One recent warm afternoon, Jamal Abdulhadi Mahameed drove past kibbutz fields of wheat and watermelon, up a dirt road surrounded by pine trees and cactuses, and climbed the worn remains of a set of stairs, declaring in the open air: “This was my house. This is where I was born.”

He said what he most wanted now, at 69, was to leave the crowded town next door, come to this piece of uncultivated land with the pomegranate bushes planted by his father and work it, as generations had before him. He has gone to court to get it.

He is no revolutionary and, by nearly any measure, is a solid and successful citizen. His children include a doctor, two lawyers and an engineer. Yet, as an Arab, his quest for a return to his land challenges a longstanding Israeli policy.

“We are prohibited from using our own land,” he said, standing in the former village of Lajoun, now a mix of overgrown scrub and pines surrounded by the fields of Kibbutz Megiddo. “They want to keep it available for Jews. My daughter makes no distinction between Jewish and Arab patients. Why should the state treat me differently?”

The answer has to do with the very essence of Zionism — the movement of Jewish rebirth and control over the land where Jewish statehood first flourished more than 2,000 years ago.

Maintaining a Haven

“Land is presence,” remarked Clinton Bailey, an Israeli scholar who has focused on Bedouin culture. “If you want to be present here, you have to have land. The country is not that big. What you cede to Arabs can no longer be used for Jews who may still want to come.”

A Palestinian state is widely seen as a potential solution to tensions with the Palestinians of Gaza and the West Bank, but any deep conflict with Israel’s own Arab citizens could prove much more complex.

Antagonism runs both ways. Many Israeli Arabs express solidarity with their Palestinian brethren under occupation, while others praise Hezbollah, the anti-Israel group in Lebanon, and some Arabs in Parliament routinely accuse Israel of Nazism.

Meanwhile, several right-wing rabbis have forbidden Jews from renting apartments to Arabs or employing them. And a majority of Jews, polls show, favor a transfer of Arabs out of Israel as part of a two-state solution, a view that a decade ago was thought extreme.

Arabs here reject that idea partly because they prefer the certainty of an imperfect Israeli democracy to whatever system may evolve in a shaky Palestinian state. That is part of the paradox of the Israeli Arabs. Their anger has grown, but so has their sense of belonging.

In fact, the anxious and recriminating talk on both sides may give a false impression of constant tension. There is a real level of Jewish-Arab coexistence in many places, and the government has recently committed itself to affirmative action for Arabs in education, infrastructure and government employment.

“We know that they need more land, that their children need a place to live,” said Raanan Dinur, director general of the prime minister’s office. “We are working on building a new Arab city in the north. Our main goal is to take what are today two economies and integrate them into one economy.”

Still, there is a concern that time is short.

Mr. Mahameed and his fellow villagers will arrive at the Supreme Court in July with the goal of obtaining 50 acres of their families’ former land that sits uncultivated except for pine trees planted by the Jewish National Fund.

Their story is part of a larger one: After the United Nations General Assembly voted in late 1947 for two states in Palestine, one Arab and one Jewish, local Arab militias and their regional supporters went on the offensive against Jewish settlements, in anger over the United Nations’ support for a Jewish state. Zionist forces counterattacked. Hundreds of Palestinian villages, including Lajoun, were evacuated and mostly destroyed.

Palestinian Arabs became refugees in Jordan, Lebanon and Gaza, then under Egypt’s supervision. But some, like Mr. Mahameed, stayed in Israel. They were made citizens and were promised equality, but never got it.

Those who had left or had been expelled from their villages were not permitted back and have spent the past 60 years often a few miles away, watching their land farmed or built upon by newcomers, many of them refugees from Nazi oppression or Soviet anti-Semitism.

In 1953, the Israeli Parliament retroactively declared 300,000 acres of captured village land to be government property for settlement or security purposes.

Mr. Mahameed and his 200 fellow complainants live in the crowded town of Um el-Fahm near their former land.

“Our claim is that since the land has not been used all these years, there was no need to confiscate it,” said Suhad Bishara, a lawyer with Adalah, a Haifa-based group devoted to Israeli Arab rights.

She lost that argument in the district court, which agreed with the government that the pine trees and a water treatment plant in Lajoun constituted settlement. For her, the ruling is part of a long tradition of trickery by Israel’s legal and political systems that have nearly always come down against expanding Arab land use.

Ms. Bishara says Arabs occupy only a tiny percentage of Israel, despite making up one-fifth of its population. The government said it could not provide an estimate of the land use.

Still, it is not hard to detail the gap between Arabs and Jews in nearly every area — health, education, employment — and in government spending. Three times as many Arab families are below the poverty line as Jewish ones, and a government study five years ago called for removing “the stain of discrimination.”

Mr. Dinur of the prime minister’s office has taken an interest in the issue and has met several times with Arab leaders. He says it may be possible one day for some Arabs to return to their native villages, but only as part of a process of integration and regional reconciliation. Otherwise, he says, Israeli Jews will fear that the Arabs’ goal will be to take back all the territory lost in the 1948 war.

Regional Tensions

For many Israelis, the challenge posed by the Arabs cannot be separated from what they see as the risks in the region — the increased influence of Iran, the growth of Islamic radicalism, the concern that another war in Lebanon or Gaza is not far away.

Michael Oren, a senior fellow at the Shalem Institute, a research group in Jerusalem, said that when the army prepares for war, it includes in the plan how to handle the possibility of Israeli Arabs rising up against the state.

Many also believe — and here Jews and Arabs seem to agree — that without a solution to the Palestinian dispute over the West Bank and Gaza, internal tensions will not abate. And given the pessimism about the peace talks with the Palestinians, the forecast does not look bright.

For many Israeli Jews who long resisted the idea of a Palestinian state, it was the realization that they were losing the demographic battle to Palestinians that turned them around. But of course the population challenge also comes from Israel’s Arabs.

Israeli Arabs are aware of the contest. And some figure time is on their side.

“Israel is living within the Arab-Islamic circle,” Raed Salah, head of the Islamic Movement of Israel, said in an interview. “It is important to look at the Jewish percentage in that larger context over the long term.”

Abdulwahab Darawshe, a former member of Israel’s Parliament and the current head of the Arab Democratic Party, sat in his Nazareth office recently and said: “No matter what happens, we will not leave here again. That was a big mistake in 1948. Yet our identity is becoming more and more Palestinian. You cannot cut us from the Arab tree.”

Asked his plans for Israel’s Independence Day, he said, “I will take a shovel and work the land around my olive trees.”

Source. / The New York Times

Thanks to Jim Retherford / The Rag Blog