cult figure, something of a flimflammer.

The Buckminster Fuller exhibition that has just opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York has already received a lot of press coverage, with long stories in The New Yorker and the New York Times. The latter ran a sensational report suggesting that Fuller’s depression and near suicide at age 32—which he famously described as spurring him to embark on his lifelong creative quest—were more or less invented, and that if he had a midlife crisis, it occurred later, as a result of a failed extramarital affair.

The Times story is titillating, but it pales beside the revelation made 35 years ago by Lloyd Kahn, an early geodesic dome devotee. The geodesic dome, a spherical structure constructed out of small elements that make it lightweight and extremely strong, was long associated with Fuller. Kahn revealed that the world’s first geodesic dome was a planetarium designed for the Carl Zeiss optical works in Jena, Germany, by Dr. Walter Bauersfeld in 1922—30 years before Fuller filed his patent for the device.

Neither the Jena dome nor the extramarital affair figure in the Whitney show, which is content merely to celebrate its subject (and repeats the old chestnut that Fuller “developed” the geodesic dome). That’s a shame since Fuller was a complex individual, and one not to be taken at face value. He is sometimes described as a global man, yet he was a quintessentially early-20th-century American type: the inventor who bootstraps himself out of obscurity, the self-promoter who turns into an inspirational cult figure, the tireless proselytizer who is also something of a flimflam man.

Fuller did not invent the geodesic dome, but he certainly popularized it, and in the 1950s domes were used by various American government departments as temporary shelters for traveling exhibitions and by the military, notably for building so-called radomes, housing radar installations in the Canadian Arctic. The geodesic dome became such a widely recognized icon of American know-how that it was used with great success as the U.S. pavilion at Expo 67, the Montreal world’s fair.

Most of Fuller’s inventions found less success. His most durable creation may have been his brand name, “Dymaxion,” a combination of dynamic, maximum, and ion, which conveyed his intention to radically rethink the design of everyday objects. The first Dymaxion House, octagonal in plan and suspended from a central mast, existed only in model form. The Dymaxion Bathroom, a prefabricated two-piece module that used a finely atomized spray instead of a conventional shower, made it to the prototype stage. Only three Dymaxion Cars were built, and the sole surviving prototype is on display in the Whitney. It’s worth the price of admission. The car looks like an airplane without wings, a three-wheeled lozenge that can turn in its own length. The elegant form owes a lot to W. Starling Burgess, a pioneering aeronautical engineer and renowned naval architect who designed several America’s Cup defenders. To obtain Burgess’ services, Fuller commissioned him to build a Bermuda-class sailing yacht, which he christened Little Dipper.

Burgess, who invented and flew the first Delta-wing airplane, is a reminder that Fuller’s period was replete with self-taught inventors. Many turned their attention to the problem of shelter. Wallace Merle Byam, an attorney, advertising executive, and publisher, invented and manufactured the Airstream trailer using airplane-building technology similar to the Dymaxion Car. The now-forgotten Corwin Willson built a two-story trailer house prototype using thin-shell-veneered plywood. Konrad Waschmann, a German immigrant, teamed up with Walter Gropius to design an ingenious prefabricated housing system using interlocking wood panels.

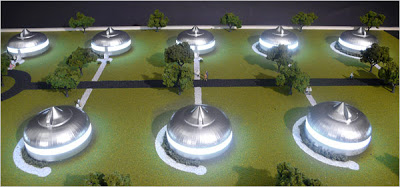

Waschmann and Gropius’ General Panel Corp. ultimately failed, and the closest that anyone ever came to realizing the age-old dream of a factory-produced home was probably Fuller’s Dymaxion Dwelling Machine. The all-aluminum house, which resembled an 18-foot-diameter flying saucer, incorporated dozens of innovations such as Plexiglas windows, a huge rotating ventilator that exhausted air from the interior, and revolving storage shelves. The whole thing weighed 6,000 pounds, could be transported in a compact cylinder, and sold for today’s equivalent of $50,000. The Dwelling Machine garnered immense publicity—including more than 37,000 unsolicited orders. Fortune magazine predicted that the dwelling machine would have a greater social impact than the automobile. Curiously, part of the reason for the project’s ultimate failure was Fuller himself: He cautiously delayed putting the house on the market for so long that in 1946 his company—the publicly traded Fuller Houses—finally collapsed.

A model of R. Buckminster Fuller’s “Dymaxion Dwelling Machines” community, about 1946. An exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art will offer a review of some of his grandest designs. / NYT

Many of the rooms in the Whitney exhibition contain flat-screen televisions playing films of Fuller. Martin Pawley, who wrote a biography of Fuller, described him as “perhaps one of the most prolific public speakers ever to remain outside politics,” and Fuller’s wide influence, especially later in his life (he died in 1983 at the age of 87), derived in no small part from his oratory. I heard him lecture several times in the 1970s, both in large and small groups. He had a flat, humorless, somewhat monotonous voice and spoke in a kind of verbal shorthand that was sometimes difficult to follow. Occasionally he appeared breathless, not out of any infirmity, but because—one had the impression—his brain was transmitting ideas faster than he was able to speak. The unlikely effect was captivating nonetheless.

Although the Whitney show describes Fuller as “one of the great American visionaries of the 20th century,” his influence today is hard to gauge. He had a short-lived influence on the counterculture of the 1960s, inspiring the Whole Earth Catalog and countless do-it-yourself domes. He also had an important influence on architects such as Richard Rogers, Renzo Piano, and Norman Foster (it’s hard to see the Hearst Tower, across town from the Whitney, as anything except Foster’s hommage to Fuller). It is tempting to see Fuller, with his emphasis on maximizing resources and reducing waste, as a harbinger of green architecture, but he was less interested in environmentalism than in efficiency. I once heard him answer a question about recycling a waste material: “No, no, you should never use something just because it’s available; you should always find the best solution to a problem.” The Whitney exhibition catalog makes an unconvincing case that Fuller was a kind of artist and tries to find links to his work in the art world. Anyone interested in Fuller would do better to find a copy of The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, by Fuller and Robert Marks, now out of print. This book contains a pithy description of Fuller’s philosophy, which, in our present condition of diminishing resources and environmental challenges, remains as pertinent as ever: “rational action in a rational world demands the most efficient overall performance per unit of input.” Vintage Bucky.

Source. / Slate

Also see Dymaxion Man / The New Yorker

And The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller / The New York Times

The Rag Blog