R. Crumb’s Underground: ‘The exhibition is full of wild sex’

By Ken Johnson / September 4, 2008

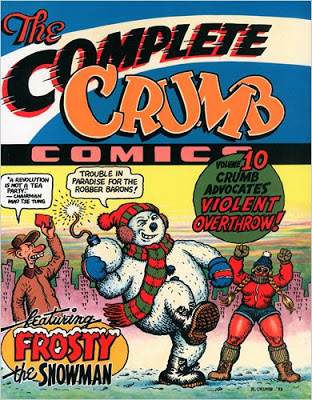

PHILADELPHIA — What a long, strange trip it’s been. Over the course of his five-decade career the comic artist R. Crumb has gone from hero of the hippie underground to toast of the international art world. Founder of the deliriously psychedelic and ribald Zap Comix during the Haight-Ashbury wonder years, he has more recently contributed comic strips made in collaboration with his wife, Aline Kominsky Crumb, to The New Yorker. In 2004 he was included in the Carnegie International and had a career retrospective at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, Germany.

Now the Institute of Contemporary Art here offers “R. Crumb’s Underground,” an excellent opportunity to ponder Mr. Crumb’s incredible journey. This enthralling selection of more than 100 works from all phases of his career was organized by Todd Hignite, the publisher and editor of Comic Art magazine, for the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, where it was on view in 2007.

Mr. Crumb is not the only artist to cross over from the comic-book ghetto to the fine-art museum. Gary Panter, Chris Ware and Daniel Clowes are just three of the better-known contemporary cartoonists who have helped to make the comic book a form to be taken seriously by sophisticated adults. But Mr. Crumb — a draftsman of transcendent skill, inventiveness and versatility, a fearlessly irreverent, excruciatingly funny satirist of all things modern and progressively high-minded, and an intrepid explorer of his own twisted psyche — remains the genre’s gold standard.

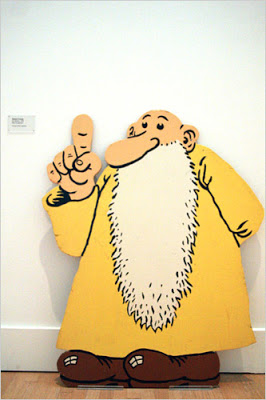

Born in Philadelphia in 1943, Mr. Crumb (first name, Robert) never went to art school. He learned to draw under the tutelage of his older brother, Charles, also an aspiring comic artist. In the early 1960s he designed greeting cards for the American Greetings Corporation in Cleveland. In 1967 he moved to San Francisco, where he would create some of the most memorable characters in cartoon history, including the irascible guru Mr. Natural and his hapless foil Flakey Foont; the suave, shamelessly randy Fritz the Cat; the angry amazon Devil Girl; and R. Crumb himself, a figure comparable to the autobiographical alter egos of Woody Allen and Philip Roth. Since the early 1990s Mr. Crumb and his wife have lived in the South of France.

The exhibition is full of wild sex. Mr. Crumb makes no bones about his lust for big, muscular women, and his uncensored erotic fantasy life is not only entertaining but also liberating. See “How to Have Fun With a Strong Girl” (2002), a suite of 12 drawings in which the scrawny Mr. Crumb climbs like a monkey all over a powerfully built young woman. We should all be so open to, and forgiving of, our libidinous fantasies.

But sex is not Mr. Crumb’s only preoccupation. He is also a great lover of early-20th-century popular music and a fanatical collector of old 78-r.p.m. records. A section of the exhibition devoted to his musical interests includes extended narratives about the sadly foreshortened lives of the blues musicians Charlie Patton and Tommy Grady. There is a humane, deeply moving tenderness to these works.

The influence of LSD, which Mr. Crumb has called his “road to Damascus,” is evident in works of funky surrealism from the ’60s and ’70s. The classic “Meatball” (1967), in which ordinary people from all walks of life are hit from out of the blue by consciousness-altering meatballs, is mysteriously trippy.

But what is also appealing in Mr. Crumb’s work is how often it is grounded in mundane reality. “Lap o’ Luxury” (1977), at 10 pages one of his longer productions, tells in detail all the events in one afternoon in the life of a little boy at home with his mom and his pesky younger brother. At one point he becomes sexually aroused by the cowboy boots on a woman who comes for a brief visit, but otherwise it is all good, clean fun.

Viewers should set aside two or three hours to take in this show. It requires a lot of reading, which brings up another of Mr. Crumb’s virtues: he is a gifted writer with a great ear for vernacular speech. An argument can be made that Mr. Crumb’s work is best consumed in book form. But there really is no substitute for seeing the original drawings, most of which are made with a fine black Rapidograph pen. The liveliness of his curiously old-fashioned draftsmanship comes across in print, but no reproduction can capture his subtlety of touch and alertness to the act of drawing.

Whatever the aesthetic and formal attractions of his work, Mr. Crumb’s penchant for barging past the limits of good taste and political correctness into psychologically juicy and dangerously complicated territory is still the main draw. His most amazingly provocative creation is Angelfood McSpade, a young, inky black, big-breasted African woman in a palm leaf skirt who was inspired by racist caricatures of the ’20s and ’30s. Sweet-tempered and dimwitted, the long-suffering Angelfood is subjected to all kinds of sexual abuse in various episodes Mr. Crumb has drawn. In one hilarious strip in the exhibition she is abducted and molested by aliens in a U.F.O.

Mr. Crumb’s outrageous play with the Angelfood character hinges on a theory that all people are at least unconsciously racist and that bringing racist fantasies fully to light is the best way to expose how stupid and cruel yet insidiously compelling they can be, especially when mixed with sexual fantasies. Kara Walker and Robert Colescott have toyed with racist stereotypes to similar ends.

But Angelfood represents something else for Mr. Crumb too. At the end of a zanily eventful four-page narrative from 1968 we see her dancing in the forest. “She spends her time bopping around in the jungle,” reads the caption, “just a simple, primitive creature! But if you dig her, go get her! If you dare!” In the final panel a man in a suit and tie hurries along a path in the opposite direction from a sign pointing to “Schmarvard Law School.” The words on his suitcase say, “Darkest Africa or Bust!”

Angelfood, in other words, is a symbol of modern man’s yearning for reconnection to his own misplaced instinctual life. In a sense that has been Mr. Crumb’s own lifelong mission: to stay imaginatively alive to his own deepest and most urgent desires, however embarrassing, distasteful or offensive they may appear to polite society. Angelfood is R. Crumb’s soul.

[“R. Crumb’s Underground” continues through Dec. 7 at the Institute of Contemporary Art, 118 South 36th Street, Philadelphia; (215) 898-7108, icaphila.org.]

Source / New York Times

Thanks to Harry Edwards / The Rag Blog

I’m sorry I’m not in Philly to see this show for myself, as I doubt that I would have this writer’s joyful acceptance.

As a (female) child of the ’60’s I actively boycotted R. Crumb’s comix

exactly BECAUSE of his sexist stereotyping of women. This wan’t a popular position to take back then, and evidently, it isn’t now either. Just not sure I’d find rape “hilarious” either.

Gee, why don’t feminists have ANY sense of humor?