Ernest Goldstein Pushed for Integration At University of Texas in ’50s

By Joe Holley / May 29, 2008

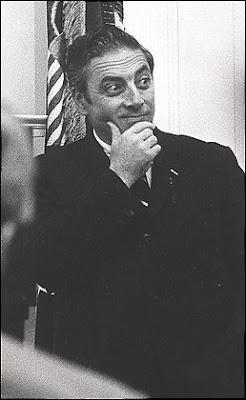

E. Ernest Goldstein, 89, a Capitol Hill lawyer who moved to Texas in the mid-1950s and played a leading role in the full integration of the University of Texas at Austin and who later served in the Johnson administration, died May 25 of Alzheimer’s disease at his home in Austin.

Mr. Goldstein was teaching law at the University of Texas when students and faculty members began protesting race-based regulations on the South’s largest campus, which had about 200 African American students among a student body of more than 20,000.

In 1961, the university’s student assembly voted 22 to 2 to integrate Texas athletic teams and 23 to 1 to integrate a men’s dormitory. The nine regents, all appointees of two segregationist governors, voted to ignore the students’ voices.

When black students held sit-ins at segregated dorms and were put on disciplinary probation, Mr. Goldstein circulated a resolution denouncing dorm regulations that “degrade the dignity of the individual, subvert the academic community and interfere with the educational process.”

He ridiculed the university’s position. “What happened,” he told Time magazine, “was they collected all the known Negroes and then they asked them, ‘Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Negro race?’ “

Ronnie Dugger of the Texas Observer reported that a mathematics professor challenged Mr. Goldstein during a faculty meeting: “Why did you accept the tradition here? Why did you come?”

“Because I knew what the law of the land was, and I assumed the university would progress with the rest of the world,” Mr. Goldstein responded.

The faculty assembly adopted his resolution by a vote of 308 to 34, but the regents continued to insist that the integrationists were a “vocal minority.”

“When students gathered outside the faculty assembly to applaud their teachers, Goldstein (by this time the clear leader of a popular revolt) appeared in an open window, coattails flapping, to encourage the legal fight,” Time reported.

“He didn’t go looking for a fight; he just had a fierce sense of fairness,” said his son, Daniel Goldstein of Baltimore.

Mr. Goldstein was born in Pittsburgh and graduated cum laude from Amherst College in 1939. He studied at the University of Chicago Law School from 1940 to 1942 and received a law degree from Georgetown University in 1947. He received a doctorate of law from the University of Wisconsin in 1956.

During World War II, he served as an Army Security Agency cryptanalyst at Arlington Hall, where he helped to break coded German naval communications. He received the Legion of Merit.

He practiced law with the Washington firm of Pike and Fisher before joining the Justice Department. He served as counsel to the House antitrust subcommittee chaired by Rep. Emmanuel Celler (D-N.Y.) during its investigation of baseball’s reserve clause and as counsel to the Senate committee chaired by Estes Kefauver (D-Tenn.) that investigated organized crime.

In 1952-53, he was a restrictive-trade practices specialist to the U.S. mission in Paris and the U.S. representative to the Productivity and Applied Research Committee of the Organization for European Economic Cooperation. A run-in with Harold Stassen, director of the Foreign Operations Administration during the Eisenhower administration, left him out of work for nine months. Stassen, according to Mr. Goldstein’s son, questioned the loyalties of some of Mr. Goldstein’s associates.

He became a professor of law at Texas in 1955 and taught international law, trademark and copyright law and government regulation of competition.

In 1966-67, he served as counsel to Coudert Frères in Paris, then joined the Johnson administration as special assistant to the president. In 1968, he rejoined Coudert Frères as a partner, living in Paris and Switzerland before returning to Austin in 1992.

For years, Mr. Goldstein was an inveterate writer of letters to the editor. In a 1948 letter to The Washington Post, he decried the segregation policies of the National Theatre and Lisner Auditorium and proposed a committee of District residents who would “underwrite four or eight weeks of full, nonsegregated houses at the National. . . . Should we not demonstrate the willingness of the majority to attend a nonsegregated theater?”

In another letter to The Post years later, he chided Jack Valenti, who also worked in the Johnson White House, for claiming that presidential assistants missed the joy of power. Mr. Goldstein wrote that he and others “neither sought nor obtained an extra client or dollar because of the LBJ connection.”

Mr. Goldstein’s wife, Peggy Goldstein, died in 2003.

In addition to his son, survivors include a daughter, Susan Lipsitch of Atlanta; four grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

Source. / Washington Post

When I got to UT in September 1963 the dormitories were all segregated. This was becoming somewhat of an embarrassment for Vice President Johnson and after the President was assassinated in Dallas it became even more so for the new President who had a daughter living in Kinsolving. I am not acquainted with the civil rights movement prior to the fall of 1963 but during 1963-1964 I never heard of any movement to integrate the dorms. Just before graduation in June 1964, Charlie Smith, with me as a look-out, slipped in through a little known unlocked door in Kinsolving at 3:30 a.m. and put leaflets under the doors with the message that there would be big demonstrations at Commencement if the dorms weren’t integrated. This was all a bluff since we were going to Mississippi and nobody knew about it but Charlie and me. But, to our surprise, they did integrate the dorms. Not because of us for sure, but maybe we were the straw that convinced them. President Johnson was coming to UT and didn’t want to be embarrassed.

A sidelight is that the alumni didn’t want their daughters forced to live in a dorm room with a black woman so they abolished the rule that all women had to live in approved housing and be in by 10 p.m.. They could move out of the dorm, get an apartment off-campus and stay out all night if they wanted rather than live with a black person. That opened the door for the SDS communal houses, all night meetings etc etc.

Robert Pardun / The Rag Blog

Thanks to Doyle Niemann / The Rag Blog