Stop the Loss:

Austin veterans turn away from Iraq and war

By Richard Whittaker / December 19, 2008

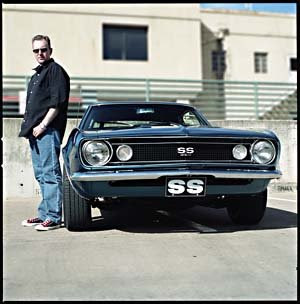

Eight years ago, Casey Porter and his father started rebuilding a ’68 Chevrolet Camaro. It was a junker with no paint and no engine, and getting it roadworthy was a family project. But for the last four years, progress has been slow. That’s how long Porter’s been in the Army. For 21 months, he’s been “stop-lossed,” the U.S. Army’s way of keeping soldiers enlisted beyond their original contract. Now Porter is eight months into his second Iraq deployment, engaged in a war that he, like many other soldiers and veterans, no longer believes in.

So now he has a new project: making films about the reality of life in Iraq for U.S. military personnel.

These aren’t rough clips of gory attacks that spark online controversy, and they’re definitely not gung-ho recruitment ads. Nor are they the 30-second casualty reports or the congressional committee coverage that too often pass for “war reporting.” It’s one soldier talking to other soldiers about his or her experiences, then using the Internet to let everyone else know what’s going on. Using a $150 off-the-shelf camcorder, a laptop, some editing software, and a YouTube account, Porter has created short documentaries to show to his viewers the raw, unvarnished truth. “There might be music, and I might have some flair in my videos, but they’re not getting a government-sanctioned version,” he said.

That doesn’t mean Porter’s footage, of life in a war zone, is not brutal. He shows acts of kindness as well, such as sharing rations with children. But there are the roadside bombs and the body parts, the badly maintained military facilities and the wrecked streets, the sandstorms and the fireballs. It’s nothing that hasn’t been talked about – but to see it, five years into the occupation, makes quite a remarkable impact.

Some of Porter’s tales are heartrending. In “The Story of Two Dogs,” the fate of a pair of puppies his unit adopted is a savage indictment of the linear military mindset. In the simpler “Miller’s Story,” a comrade explains what it’s like to survive a mortar attack. Porter’s latest, “Deployment Game: Living FOBulous,” was shot inside the post exchange – imagine a Best Buy crossed with a Wal-Mart and a car dealership, then add incoming mortar rounds – at Camp Taji, north of Baghdad. (“FOB” is Army lingo for “forward operating base,” a secure camp away from the main base.) For Porter, it’s all part of the way troops are being misused. As one soldier tells him in “Deconstructed”: “It’s going to take a lot of stuff to fix this bruise we’ve put on the whole earth.”

Challenge and Disenchantment

Arranging a meeting with Porter, like everything else in his military career, took longer than it should have. First there were phone conversations from Iraq, plagued with a four-second signal delay (“It takes a little time for the CIA to listen in,” he joked in his first call). Then his leave, originally scheduled for October, was pushed back to late November. His flight stateside had long layovers in Ireland and Dallas. When he finally made it to Katz’s Deli and ordered a burger (“I eat rare meat. Now you know the worst thing about me,” he grinned as he slathered on some cream cheese), he was greeted by the staff like a regular who had just stepped out for a moment.

Porter doesn’t look like a returning warrior, and he didn’t plan to be one. From age 11, when he first saw Terminator 2, he wanted to make films, but as an adult he tired of surviving on nickel-and-dime jobs. The Army was a change and a challenge. “I think, for a man in American society, we question, ‘What can we handle?'” he said. “I had some misgivings about the war, but I didn’t question whether I believed in the fight. I put it on the back burner, like most Americans. But almost immediately I realized, in basic training, I had made a mistake.”

When he was deployed to Iraq for his first tour in December 2005, his disenchantment worsened. “There’s no reconstruction going on at the level they show you,” he explained. “The soldier’s mission is to survive. Not to win the fight, not to fight the enemy that is the main threat to the United States, but to simply survive. You’re sent on these missions that don’t make any sense, you’re patrolling these roads that you don’t care about, and the people on that road really don’t want you there.”

He was away from the Camaro, but as an Army mechanic, he was still fixing vehicles. First it was tanks, then the new mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicles, designed to survive improvised explosive devices – Iraq’s infamous IEDs. Being the unit film geek also paid off, as his first sergeant made him the company photographer. “What I basically ended up photographing was funeral services,” he says, “and stuff from outside the wire.”

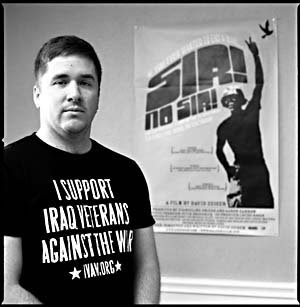

During his first tour, from December 2005 to November 2006, he took footage with no real goal in mind, but when he returned to Texas in November 2006, the filming quickly became part of his anti-war protest. He joined Iraq Veterans Against the War and found he could use the footage he had gathered. “I came back and realized that filmmaking was still in my blood, something I never should have walked away from,” he explained. Through IVAW, he started showing his documentaries at colleges. “I would talk, show a film, talk, show a film, and then there would be these Q&As. What I realized was that these films – while they were [posted] online – in person, they had a strong emotional impact.”

Part of what frustrated him was the media coverage, which he knew was misleading or just wrong. Too often, Porter explained: “There’s a guy reporting live from the streets of Baghdad, and it’s total bullshit. He’s completely inside the [heavily protected] Green Zone.” Not that anyone who doesn’t know Baghdad intimately would know that. “There’s a big disconnect between the military service and civilian populations, and that works to the advantage of the military and the government, because they can pack so much bullshit in that big gap.”

Showing protest movies in Austin and filming them in Iraq are two quite different things. Porter knew he was at risk of being stop-lossed: After his first tour, he’d been transferred out of his unit to one more likely to be deployed. His contract, expiring January 2007, got extended, and under the lesser-known “stop-movement” program, he couldn’t transfer out to another unit less likely to be deployed. Then last December he got confirmation: His second Iraq tour would start in March 2008. This time, Porter was ready, and his decision was simple. “No wife, no kids, no debt. So you know what? I’ll make films about what I see.”

Making his movies, like being a member of IVAW, is completely legal under Army regulations: He has a civilian lawyer to review the films and posts them with all the necessary disclaimers. The problem for Porter is that some military personnel and most Iraqi civilians are nervous about talking on camera. It’s too risky, for their lives or their careers or both. “I need to expose people to what they’re not seeing,” he said, “but my only concerns are soldiers’ safety and the Iraqis’ safety.” The most important thing, he finds, is letting people know what he’s doing, so they have the chance to back out. “You may get someone on camera who just thinks you’re doing it for yourself, and that Iraqi is having to explain to somebody why he’s on YouTube with the Americans,” he said.

Yet while some people are cautious about being on camera, the finished films are popular with the troops. Well, mostly. “Lifers, they’re upset about it,” he explained. “Their whole career in the Army is spent in preparation [for] the mission, a mission, any mission. They say, ‘How dare you question it?’ and I say, ‘Well, why shouldn’t I?'” But among those on short contracts, he said, “I have guys who’ll throw me a peace sign on the sly.” He also doesn’t buy the line that it’s bad for troop morale – because it’s the troops that help him make the films. “When they see the footage they’ve given me, they see it edited and color-treated, they feel a part of something.”

Honoring the Contract

Porter is not the only Central Texas veteran speaking out. Los Angeles native turned Austin resident Ronn Cantu volunteered for the Army on March 9, 1998, for four years. His contract expired just after the 9/11 attacks. Since there was no stop-loss then, he was out. But he started to reconsider his future on Feb. 5, 2003: The day Secretary of State Colin Powell made his now-infamous presentation on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction to the United Nations Security Council. “I remember watching … and buying into it hook, line, and sinker,” said Cantu. His good memories of the Army helped: “In 1998, in the quote-unquote peacetime, I couldn’t take 10 steps without someone pulling over and offering me a ride to where I needed to go. There was a lot of camaraderie, a lot of esprit de corps and high morale.” So he re-enlisted as a sergeant.

Almost immediately, he knew something was wrong. The camaraderie was gone, the quality of recruits was dropping, and then in 2004, he was deployed to Iraq. “Some of us joked we were only there to test our armor, but none of us could understand why our brothers and sisters were dying,” he said. “I really felt betrayed, because we were not doing what I and the rest of the country were told we were supposed to be doing, and that’s helping the people.”

After his first tour, he returned to Fort Hood. With his unit broken up, he had no one to talk to who had shared his experiences, until finally he found Iraq Veterans Against the War. Then he heard he was going back to Iraq. Like Porter, he tried to make it as palatable as possible, switching from infantry to interrogation. After his second deployment, while publicly criticizing the war, Cantu faced possibly the strangest moment of his military career. “They made me a staff sergeant. No board [interview], no questions asked, just, ‘Here’s your extra rank, here’s your extra money, but by the way … you don’t get anyone below you.'” Automatic promotions above one-stripe privates, he said, are “a sign of how much the military is breaking down and losing leadership.”

While Porter and many others have made clear their opposition to the war, they still have a job to do. Porter explained: “I’m honoring the contract. I work hard; I don’t do shortcuts. One person in the anti-war community suggested I do sabotage. Absolutely not. I’m doing this, obviously for the Iraqis but for the other soldiers, because they’re the ones in the wringer.”

That attitude doesn’t surprise Cantu. “I haven’t seen Casey run from anything,” he said; but he understands why other soldiers are afraid to speak out and instead just keep their heads down. “If you get anything less than an honorable discharge or get jail time, that can really ruin your future,” he said. “The military attracts recruits by selling hope. They tell them: ‘We can make your life better. You need a steady job, and we can give you a steady job, with security.’ Nobody enlists to make their life worse. Nobody holds their hand up to take that oath thinking they’re going to go to jail for something they don’t believe in.” That’s something that radical anti-war activists don’t understand, he said. “The people that tell you to go AWOL aren’t offering you a job at the same time.”

The Chaplain’s Passion

For others, leaving the military immediately is the only option. Like Cantu, Benjamin Hart Viges isn’t a native Texan, having traveled before joining the Army. That’s what brought him to Austin, where he is now the unofficial chaplain for the local IVAW branch. “I’m building my roots here,” he said. “I’ve given up moving.”

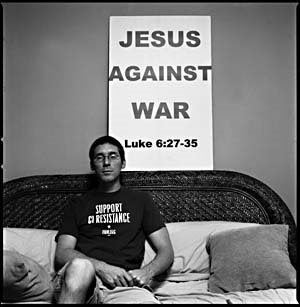

His story almost reads like a recruitment poster. “I joined the Army because of September 11 and went to Iraq in the initial year of the invasion in the 82nd Airborne Division.” For Viges, his Christianity is his bedrock; he was baptized in Baghdad. (“I was pissed when I didn’t get to go to Ur, the birthplace of Abraham,” he half-joked.) After returning, his resistance to the war became an act of religious devotion, but it took time. He said: “I thought that we’d done a good thing. I held on to that string that we’d got rid of Saddam.” It was then that he met his future fiancée, Alejandra, who placed in him what he calls “the burning question of why. In the same period, I saw the film The Passion of the Christ, and it gave me my language to resist.”

Viges applied for conscientious objector status, entering a battle with the Army bureaucracy. First there’s a lengthy form, he said, “Then you go through three interviews: One with a psychiatrist to show you’re not insane, one with a chaplain to verify how sincere you are and when you crystallized your belief, and one with an officer to rip you a new one.” After that, the paperwork went to the Department of the Army where “it has a 50-50 chance of being accepted,” he said. Not only was his accepted, but he went on to get his taxes exempted from being put toward military spending. “I realized that my real tax dollars buy real bullets that kill real people,” he said, “and that violated my conscientious objector status that I legally obtained through the Army.”

Now, in between working in a cafe, writing his memoirs, and planning to return to college to study theology, Viges has become a passionate and well-traveled voice against the war. He has spoken before the French, German, and European Union parliaments. Closer to home, he has spoken all around Texas, as well as taking calls on the GI Rights Hotline. “Sometimes,” he said, “I make a big ‘Jesus Against War’ sign and walk around Downtown Austin.” If kids want to serve, he points them toward organizations such as AmeriCorps, to change the dynamic of the military as the solution to all personal, professional, and international ills. “Doctors and teachers are peacetime reconstruction. When you carry a gun, the intimidation level is there.”

Sucking It Up

For Viges and Cantu, the war is over. In April, Cantu also applied for conscientious objector status. “I had taken a human life, and this is not how human beings are supposed to be treating each other,” he said. In August, he told his battalion executive officer that he would rather go to jail than do a third tour in Iraq. On Nov. 6, with 13 months left on his contract, he was honorably discharged. “I think they didn’t want to look bad, punishing a staff sergeant with 10 years experience who’s been there twice before with no bad marks on his record,” he said. What makes him suspicious is that three other active members of IVAW’s Fort Hood branch also got their walking papers early in the last month – effectively breaking up the branch.

Like Cantu, Porter’s been promoted out of harm’s way. “I’m a sergeant now,” he explained. But again, Porter feels the promotion works to the Army’s advantage, as it moved him away from his friends and comrades. Now he spends his days watching the radio. “They used this to boot me out of the unit,” he said, “and they won’t give me any soldiers to lead. But that’s OK, because they come up to talk to me.”

Porter’s leave was up on Dec. 10. He’s got another seven months left in the Army. “I’m not really worried about getting stop-lossed again,” he said. “I’m worried about being on the active ready reserve list, of being out for a year and getting called back.” As much as he looks forward to being back home, he knows how hard it can be, maybe even harder than just staying in. “There’s a term, ‘suck it up, and drive on,'” he said. “When I’m home, I try to readjust to civilian life. Like today, I’m in a really good mood, because it’s my first day back. But when I was back last time, it was, well, wait a minute, you’ve got to get back to real life again, and there’s that adjustment.”

But there’s one thing waiting for him when he leaves the Army. While he was on this current deployment, his father finished the Camaro. When he last saw it, the hood and the grill were off, and the chrome wasn’t finished. Now it sits off Sixth Street, its metallic paint iridescent in the sun. As he hits the ignition switch, it rumbles to life, and Casey grins.

Source / Austin Chronicle

Casey Porter’s videos can be viewed here.

Also see Austin : Iraq Veterans Speak Out Against the War by Susan Van Haitsma / The Rag Blog / Nov. 13, 2008

And BOOKS: Iraq Occupation Through Eyes of U.S. Soldiers by Dahr Jamail / The Rag Blog / Sept. 17, 2008

And GI’s Voice Dissent : War-Torn Vets Speak Out by Claudia Feldman / The Rag Blog / April 19, 2008

Thanks for re-posting this. The more that see our stories, the better.

He got the car up and running.

http://thisainthell.us/blog/?p=13935