Postmodern democracy

and the end of history

By Marc Estrin / The Rag Blog / July 5, 2010

“The Balance of Terror is the Terror of Balance.” (60)

[This is the second of a three part series on the philosopher and social critic Jean Baudrillard, who died three years ago at the age of 77. Go here for Part I.]

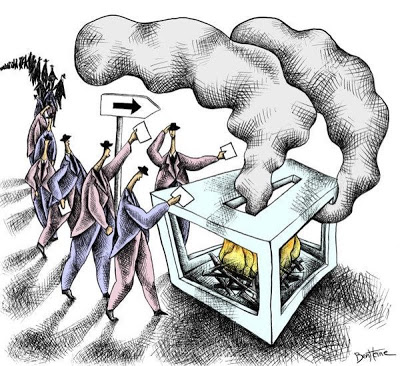

So what of democracy, the great Enlightenment goal? Is there now only a democratic simulacrum? What is the demos, the “fantastic silent majority characteristic of our times” thinking and doing in its silent postmodernity?

The masses in “advanced” democracy

In Dostoevsky’s brilliant chapter, “The Grand Inquisitor,” Jesus comes back to earth during the Inquisition, and is arrested and interrogated by the Grand Inquisitor, “a man of almost ninety, tall and erect.” Jesus says nothing throughout the moving and remarkable monologue of his adversary. The supposed Savior is condemned for lack of compassion:

[GRAND INQUISITOR:] Instead of seizing men’s freedom, You gave them even more of it! Have You forgotten that peace, and even death, is more attractive to man than the freedom of choice that derives from the knowledge of good and evil… Instead of ridding men of their freedom, You increased their freedom, and You imposed everlasting torment on man’s soul… Had you respected him less, You would have demanded less of him and that would have been more like love, for the burden You placed on him would not have been so heavy. Man is weak and despicable… We [the Church] have corrected your work.

Baudrillard meditates on the same material.

Choice is a strange imperative. Any philosophy which assigns man to the exercise of his will can only plunge him in despair. For if nothing is more flattering to consciousness than to know what it wants, on the contrary nothing is more seductive to the other consciousness (the unconscious?) than not to know what it wants, to be relieved of choice and diverted from its own objective will. It is much better to rely on some insignificant or powerful instance than to be dependent on one’s own will or the necessity of choice. Beau Brummel had a servant for that purpose. Before a splendid landscape dotted with beautiful lakes, he turns toward his valet to ask him: “Which lake do I prefer?”

In the Sixties, and even now, the (New) Left called for “empowering people to make the decisions that affect their lives.” But that assumes people know what they want, or at least want to find out. Baudrillard demurs:

Not only do people certainly not want to be told what they wish, but they certainly do not want to know it, and it is not even sure that they want to wish at all.

But while most commentators — Chomsky, the Frankfurt School — would see this as the surrender of the masses to the designs of Power (Dostoevsky: “Man is weak and despicable.”), Baudrillard challenges us to see things another way.

Whom does this trap close on? The mass knows that it knows nothing, and it does not want to know. The mass knows that it can do nothing, and it does not want to achieve anything. It is violently reproached with this mark of stupidity and passivity. But not at all: the mass is very snobbish; it acts as Brummel did and delegates in a sovereign manner the faculty of choice to someone else by a sort of game of irresponsibility, or ironic challenge, of sovereign lack of will, of secret ruse.

The ruse of silence: the mass’s way of resisting manipulation.

About the media you can sustain two opposing hypotheses: they are the strategy of power, which finds in them the means of mystifying the masses and of imposing its own truth. Or else they are the strategic territory of the ruse of the masses, who exercise in them their concrete power of the refusal of truth, of the denial of reality.

Understanding media…

…is crucial, for it is the media which cooks up reality stew and invites the masses to dinner.

We must think of the media as if they were…a sort of genetic code which controls the mutation of the real into the hyperreal. (55)

But the question of whether the masses eat or are eaten remains unsettled.

There is an over-circulation of ideas, of the most contradictory ideas, all in the same flux of ideas. What happens is that their specific impact is wiped out. I mean their negativity is wiped out. Mass media, and all that, are not vehicles for negativity. They carry a kind of neutralizing positivity.

Which means that even the negative is positive. It’s true. Iran-Contra created the stardom of Ollie North. It was fascinating, and everyone was excused. Anita Hill accused Clarence Thomas and we are all the better now for understanding sexual harassment, and the pundits taunted us “They can’t both be telling the truth,” and Clarence Thomas sits on the Supreme Court. And then, OJ flees from the police in what becomes the most watched chase scene in TV history. Isn’t actuality wonderful? Remember those fascinating L.A. riots? No matter how negative the event, just reporting it shows us that “The system works!”

What kind of person does this self-affirming recursiveness create? Democracy depends upon an informed public, but

Is information really information? Or on the contrary, will it produce a world of inertia? Will it produce, by its very proliferation, the inverse of what it wants to? Doesn’t it lead to a world, a universe in reverse, of resistance, inertia, circulation, silence and such like… It is by information that one is supposed to bring consciousness to the world, to inform and to awaken the world, but it is this very information through its very media which produces the reverse effect.

It would seem that in this simulated postmodernity, the conditions of democracy are far from being met, and all of us are largely consigned to inconsequential states of obeying and resisting a bland hyperreality.

Our relationship to this system is an insoluble “double bind” — exactly that of children in their relationship to the demands of the adult world. They are at the same time told to constitute themselves as autonomous subjects, responsible, free, and conscious, and to constitute themselves as submissive objects, inert, obedient, and conformist. The child resists on all levels, and to these contradictory demands he or she replies by a double strategy. When we ask the child to be object, he or she opposes all the practices of disobedience, of revolt, of emancipation; in short, the strategy of a subject. When we ask the child to be subject, he or she opposes just as obstinately and successfully a resistance as object; that is to say, exactly the opposite: infantilism, hyperconformity, total dependence, passivity, idiocy.

Does this seem an apt description of the electorate?

I don’t know what people are looking for. They have been taught to look for things like happiness, but deep down that doesn’t interest them, any more than producing or being produced.

The masses are playing dead…They are no longer involved in a process of subversion or revolution, but in some gigantic devolution from an unwanted liberty…

The drive to spectacle is a more powerful instinct than self-preservation.

And this suggests an explanation for a phenomenon perplexing now, and perplexing too, to an interviewer in 1989, who comments

President Reagan and his whole administration, his wife included, seem like an immense simulation: before he was a Hollywood B-grade actor, now he looks like a living cadaver. The astonishing thing is that no one really cares when he lies to the press or makes incredible gaffes. Even more, he’s been involved in many suspicious or illegal activities, like the Iran-Contra scandal. But basically no one in the US seems really upset; in fact, it’s as if the exposé itself, as a genre of critical or investigative reporting, had suddenly become dépassé in the eighties. Everyone knows or suspects the worst but finally remains indifferent. One might even say that the very visibility of Reagan and his suspect activities makes him invulnerable to criticism. Do you see here any confirmation of your own theories?

To which, Baudrillard replies,

Indeed. Reagan is a sort of fantastic specimen of the obscene transparence of power and politics, and of its insignificance at the same time. It’s as if everyone has become aware of the indifference of power to its own decisions, which is nothing but the indifference of the people themselves to their own representation, and thus to the whole representative system. This is accompanied by a demand all the greater for the spectacle of politics, with its scandals, morality trials, mass-media and show-biz effects. There is no longer anything but the energy of spectacle and of the simulacrum….

Reagan provided one kind of spectacle, Obama provides another. There is in President Hope and Change a kind of “anti-Teflon effect,” in which no matter what he does, he is seen by many as blameworthy. Why this curious transformation of public opinion from all-forgiving to merciless?

The conflicts have all the depth of a grade-B Hollywood movie:

Reagan — old and pitiful; The Public — magnanimous and tolerant.

Obama — young and treacherous; The Public: fierce and righteous.

Always enough white hats to go round. Self-preservation — and reality — be damned!

True, there’s a lot of theorizing there, in the disguise of “intellectual terrorism.” But notions such as Baudrillard’s are postmodern products, deep from the molten core.

Naturally, he denies it all:

I have nothing to do with postmodernism.

One should ask whether postmodernism, the postmodern, has a meaning. It doesn’t as far as I am concerned. It’s an expression, a word which people use but which explains nothing. It’s not even a concept. It’s nothing at all. It’s because it’s impossible to define what’s going on now, grand theories are over and done with… That is, there is a sort of void, a vacuum. It’s because there is nothing really to express this that an empty term has been chosen to designate what is really empty. So in a sense there is no such thing as postmodernism.

And yet Baudrillard, of all the commentators, gives the most arresting expression to this “non-existent” state. He describes a contemporary world which has burst the previous limits of Western society, a world in which all previous boundaries — male/female, art/non-art, economics/politics, etc. — have broken down, where religion becomes fashion, and revolution becomes style and colored shirts. What does a simulated hyperreality signify if not the “postmodern rupture”?

In fact, in Symbolic Exchange and Death, Baudrillard talks about the

second revolution of postmodernity, which is the immense process of the destruction of meaning, equal to the earlier destruction of appearances [in modernity’s search for the hidden authentic]. Whoever lives by meaning dies by meaning.

A second revolution, equal to that of modernity? This is hardly nothing.

“Who lives by meaning dies by meaning.” Thus Baudrillard dismisses the entire debate over the Enlightenment Project.

This intellectual, mental, metaphysical situation has through inertia managed to survive beyond its point of relevance. And it is probably from this that we get the stagnation and collapse of thought that we see today… We are dragging behind us a whole bundle of ill-digested rationalities, radicalities, that have no support, no enemies, and in which there is nothing at stake.

The old theories are irrelevant.

It is a question here of a completely new species of uncertainty, which results not from the lack of information but from information itself and even from an excess of information. It is information itself which produces uncertainty, and so this uncertainty, unlike the traditional uncertainty which could always be resolved, is irreparable.

I have the impression with postmodernism that there is an attempt to rediscover a certain pleasure in the irony of things, in the game of things. Right now one can tumble into total hopelessness — all the definitions, everything, it’s all been done. What can one do? What can one become? And postmodernity is the attempt — perhaps it’s desperate, I don’t know — to reach a point where one can live with what is left. It is more a survival among the remnants than anything else.)

The end of history

The seriousness of the postmodern rupture is attested to by Baudrillard’s musings on “the end of history”. In 1989, Francis Fukayama created an intellectual storm when he published an article with that title. His thesis was that with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the worldwide triumph of liberal democracy — at least in theory — history, as we know it — the struggle between opposing forces — was over. I mention this teapot tempest in order to contrast it with Baudrillard’s deeper, more mysterious probe.

Unlike Fukayama’s triumphal announcement, Baudrillard’s reasoning rings with affirmatory hopelessness.

A painful idea: that beyond a certain precise point in time, history was no longer real. Without being aware of it, the totality of the human race would have suddenly quit reality. All that would have happened since then would not have been at all real, but we would not be able to know it. Our task and our duty would now be to discover this point and, to the extent that we shall not stop there, we must persevere in the actual destruction.

History has been irreversibly destroyed by the virus of simulation. Although there is much “interest” in history today — there is even a History Book of the Month Club — a genuine return to an authentic relationship with history has become impossible.

And that is also part of the postmodern: restoration of a past culture, to bring back all past cultures, to bring back everything that one has destroyed, all that one has destroyed in joy and which one is reconstructing in sadness in order to try to live, to survive.

It’s true that everywhere today (and not just in the U.S.) there is a resurgence of history, or rather of the demand for historicity, linked no doubt to the weak registration rate of factual history (there are more and more events, and less and less history). We are caught in a sort of gigantic, historical backwards accounting, and endless retrospective bookkeeping. This historicity is speculative and maniacal, and linked to the indefinite stocking of information. We are setting up artificial memories which can take the place of natural intelligence.

But all this frenetic activity, all the research and data entry and hypertextual referencing do us little good in our attempt to connect.

We tend to forget that our reality, including the tragic events of the past, has been swallowed up by the media. That means that it is too late to verify events and to understand them historically, for what characterizes our era and our fin de siècle is precisely the disappearance of the instruments of this intelligibility. It was necessary to understand history while there was still history…

Now it’s too late, we’re in another world. It’s evident in the television production of “Holocaust” or even in “Shoah.” Those things will no longer be understood because notions as fundamental as responsibility, objective cause, the meaning (or non-sense) of history have disappeared or are in the process of disappearing. Effects of moral conscience or collective conscience are now entirely the effects of the media. We are now witnessing the therapeutic of obstinacy with which some try to resuscitate this conscience, and the little breath it still has left.

History has disappeared

in the ecstasy of information, the ecstasy of messages. We have disappeared in a sort of ecstasy of the media, of information circulating with acceleration across everything. And one is no longer able to put a stop to this process.

This, not Fukayama’s superficial assessment, is the deeper meaning of “The End of History”.

(Final installment next week.)

[Marc Estrin is a writer and activist, living in Burlington, Vermont. His novels, Insect Dreams, The Half Life of Gregor Samsa, The Education of Arnold Hitler, Golem Song, and The Lamentations of Julius Marantz have won critical acclaim. His memoir, Rehearsing With Gods: Photographs and Essays on the Bread & Puppet Theater (with Ron Simon, photographer) won a 2004 theater book of the year award. He is currently working on a novel about the dead Tchaikovsky.]

Also see “Marc Estrin: The Genius of Jean Baudrillard” by Marc Estrin / The Rag Blog / June 29, 2010

In other words, since Nietsche has proclaimed that God is dead, everything has been dying, history is dead, democracy is dead, all things and values are being or can be emptied out, safely becoming placeholders for any given values. If symbols are devoid of meaning then effectively they are variables, programmable placeholders through media or whoever wants power can associate any given value to.

The tech geeks shall inherit the world. Long live techies and virtual reality!