Bringing the war home: 1970-2010

Eventually we came to think that we could make a revolution, and that in any case it was our responsibility to try.

By Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn / The Rag Blog / March 22, 2010

Conscience is the sword we wield. Conscience is the sword that runs us through. — Marge Piercy

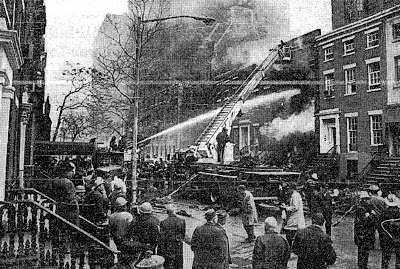

A front page headline in the New York Times on March 7, 1970, announced: “Townhouse Razed by Blast and Fire; Man’s Body Found.” The story described an elegant four-story brick building in Greenwich Village destroyed by three large explosions and a raging fire “probably caused by leaking gas” at about noon on Friday, March 6.

The body was later identified as belonging to 23-year old Ted Gold, a leader of the 1968 student strike at Columbia University, a teacher, and a member of a “militant faction of Students for a Democratic Society.”

Over the next several days two more bodies were discovered — Diana Oughton and Terry Robbins had both been student leaders, civil rights and anti-war activists — and by March 15 the Times reported that police had found “57 sticks of dynamite, four homemade pipe bombs and about thirty blasting caps in the rubble,” and referred to the townhouse for the first time as a “bomb factory.”

That awful event announced widely the existence of the Weather Underground, in some ways the most notorious, but far from the only group of Americans to take up armed struggle as a protest tool at that moment — the story took off from there, growing, changing, and accelerating every day

A few days after the Townhouse explosion Ralph Featherstone and William “Che” Payne, two “black militants,” associated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, according to Time Magazine, “were killed when their car was blasted to bits” by a bomb police said was being transported to Washington D.C. to protest the prosecution of SNCC leader H. Rap Brown. The Black Liberation Army leapt onto the national scene, and other organized groups — Puerto Rican independistas, Native American first nation militants, and Chicano separatists — emerged demanding self-determination and justice.

Violent resistance to violence was far from an isolated phenomenon: Time noted that in 1969 there had been 61 bombings on college campuses, most targeting ROTC and other war-related targets, and 93 bomb explosions in New York, half of them classified as “political,” a category that was “virtually non-existent 10 years ago.”

According to the FBI, from the start of 1969 to mid-April 1970, there were 40,934 bombings, attempted bombings, and bomb threats. Out of this total, 975 had been explosive, as opposed to incendiary, attacks, meaning that on average, two bombs planned, constructed, and placed, detonated every day for more than a year. Our national history includes times of anarchist resistance, labor militancy, massive unreported (and still largely unacknowledged) slave rebellions, and the armed abolitionism of John Brown; the late 1960’s and 1970’s was becoming one of those times.

How had it come to this?

Empire, invasion, and occupation always earn blow-back. In 1965 most Americans supported the war, but by 1968 people had turned massively against it — the result of protest and organizing and a burgeoning peace movement, and of civil rights leaders like the militants from SNCC, Muhammad Ali, and Martin Luther King, Jr. denouncing the war as illegal and immoral. Even more important, veterans came home and told the truth about the reality of aggression and occupation and war crimes.

The US government found itself isolated around the world and in profound and growing conflict with its own people inside its own borders. The Vietnamese themselves were decisive: they refused to be defeated. The Tet Offensive in 1968 destroyed any fantasy of an American victory, and when President Lyndon Johnson announced at the end of March 1968 that he would not run for reelection, it seemed to us we had won a victory.

But peace proved to be a dream deferred, for the war did not end — it escalated into an air and sea war, expanded into all of Cambodia and Laos, and every week the war dragged on another six thousand people were murdered in Southeast Asia. Six thousand human beings — massive, unthinkable numbers — were thrown into the furnaces of war and death that had been constructed by our own government.

The war was lost, but the terror continued. All Vietnamese territories outside U.S. control were declared “free-fire zones” and airplanes rained bombs and napalm on anything that moved, destroying crops and live-stock and entire villages. John McCain, an unremorseful war criminal, flew some of those missions. As a young lieutenant, John Kerry testified in Senate hearings at the time that U.S. troops committed war crimes every day as a matter of policy, not choice.

No one knew precisely how to proceed, for the anti-war movement had done what it had set out to do — we’d persuaded the American people to oppose the war, built a massive movement and a majority peace sentiment — and still we couldn’t find any sure-fire way to stop the killing; millions of people mobilized for peace, and our project, our task and our obsession, was so simple to state, so excruciatingly difficult to achieve: peace now.

The war slogged on into a murky and unacceptable future, and the anti-war forces splintered then — some of us tried to organize a peace wing within the Democratic Party, others organized in factories and workplaces, some fled to Europe or Africa or Canada, others to communes, the land, and hopeful but small organizing projects. Some began to build a vehicle to fight the war-makers by other means, a clandestine force that would, we hoped, survive what we thought of as an impending American totalitarianism.

Every choice was contemplated, each seemed a possibility then — and we had friends and family in every camp — and no choice seemed utterly beyond the pale.

The Weather Underground carried out a series of illegal and symbolic attacks on property then, some 20 acts over its entire existence, and no one was killed or harmed; the goal was not to terrorize people, but to scream out the message that the U.S. government and its military were committing acts of terrorism in our name, and that the American people should never tolerate that.

Some felt that our actions were misguided at best, off-the-tracks, indefensible and even despicable, and that case is not impossible to make. But America’s longest war itself, with all its attendant horrors, was doubly despicable, and while many stood up, who in fact did the right thing; who ended the war; who transformed the world?

We began to think of ourselves as part of the Third World project — revolutionary liberation movements demanding justice and freeing themselves from empire, we believed, would also transform the world. We thought that we who lived in the metropolis of empire had a special duty to “oppose our own imperialism” and to resist our own government’s imperial dreams.

Eventually we came to think that we could make a revolution, and that in any case it was our responsibility to try. It was a big stretch, but every revolution is impossible until it occurs; after the fact, every revolution seems inevitable.

All of that was 40 years ago — lots of water under the bridge since then, raging rivers and cascading falls, rapids and torrents, chutes and ladders — a long time in the life of a person — the young become the old, and stories get retold.

But it’s also a matter of perspective: the meaning of any historical event will always be contested, and the more recent the event, the fiercer the contestation. The last word has not been written about the radical movements of youth in Europe in 1968, and certainly the meaning of the Black Freedom Movement or of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Viet Nam and the various American reactions to that catastrophe — from mindless jingoism to sincere patriotism, from reluctant participation to gung-ho brutality, from protest to armed resistance — are far from settled.

We’re reminded of the Chinese premier Chou En Lai responding to a French journalist’s question many years ago about the impact of the 18th Century French revolution on the 20th Century Chinese revolution. He thought for quite awhile and finally said, “It’s too soon to tell.” Forty years is less than the blink of an eye.

The big wheel keeps on turning: events and actions and adventures plunge relentlessly forward and nothing withstands the whirlwind of life on-the-move and history in-the-making. No single narrative can ever adequately speak to the diversity and complexity of human experience, for meaning itself is in the mix, always contested and never easily settled.

Because meaning is made and remade in the present tense, our backward glances are now necessarily refracted through the U.S. defeat in Viet Nam, the steady decline of empire, the hollowing out of the economy through militarism, the destruction of our political system, the environmental catastrophe that capitalism wrought, the terror attacks of 9/11 and the subsequent invasions and occupations and wars that continue as defining features of our national life. There is no sturdy accounting of distant times: everything must change, no one and nothing remains the same.

Many who knew and loved them 40 years ago, choose to remember Ted Gold, Diana Oughton, Terry Robbins, Ralph Featherstone, and Che Payne every day as beautiful and committed young people who believed fiercely in peace and justice and freedom, believed further that all men and women are of incalculable value, and thought that they had a personal and urgent responsibility to act on that deep belief.

We think of Brecht: a smile is a kind of indifference to injustice. And then we turn to Rosa Luxemburg writing to a friend from prison: love your own life enough to care for the children and the elderly, to enjoy a good meal and a beautiful sunset, to embrace friends and lovers; and love the world enough to put your shoulder on history’s great wheel when required.

We have not forgotten our fallen friends, not for a moment. March 6 was for us a time of more formal remembrance. Their deaths and all that followed offered us an opportunity to reconsider and recover. We were able to recommit and to see that the first casualty of making oneself into an instrument of war is always one’s own humanity, that, in the words of the poet Marge Piercy, “conscience is the sword we wield. Conscience is the sword that runs us through.” We remember our lost comrades, their many brave, as well as their damaging last acts, and we continue to vibrate with the hope and despair they embodied then.

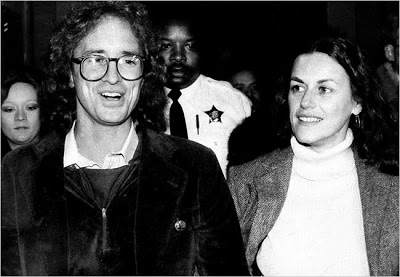

[William Ayers is Distinguished Professor of Education and Senior University Scholar at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Bernardine Dohrn is Clinical Associate Professor of Law and Director and founder of the Children and Family Justice Center at Northwestern University. Both Ayers and Dohrn were leaders in SDS and the New Left, and were founders of Weatherman and the Weather Underground.]

Peace still remains “deferred” for the wars have not ended. Without doubt the anti-war movement contributed to the eventual withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam. But violence begets violence and we have yet to actually give peace a chance.

This is pretty sick stuff. The Weatherman “armed struggle” was directed against regular, working class Americans. The bomb that blew up the townhouse and killed these SDSers, was going to be planted at a Fort Dix USO dance.

As I recall, the bombs they were making were anti-personnel bombs, filled with nails. They had become the kind of person they were fighting.

Having been around myself in the late 1960s and early 1970s time period, I’ve never challenged the motives of those who became Weather, only their strategy. Part of what is forgotten in this history is that in the fall of 1968 SDS called for a general student strike.

When that failed to materialize, it reinforced the sense of impatience many already had, especially those in the “action faction” who became RYM I, and later, Weather.

SDS was effectively imploded over the summer and fall of 1969. Yet, the spring of 1970 saw the largest nationwide campus upheaval of the entire period.

What this shows is that the march of history is not an invariably upward trend line, it is more like a roller coaster ride.

But without SDS to guide it, the spring 1970 upheavals were inchoate, and the anti-war movement essentially declined after that.

It can be said SDS exited the stage at what should have been its moment of greatest triumph. The implications of this are an important lesson to be learned.

Thanks for that, Jay. But let’s not confuse SDS with the Weather bombers. Despite Ayers-Dorhn claim that everyone in the movement was lost, SDS was clear about it’s enemy–imperialism. Not working class Americans and their wives and children who were likely to be at that USO part. Not the janitor who was missed fortunately, when those bombs went off in govt. buildings. And their hiding behind SNCC in this piece, or lumping themselves together with the Panthers as they are want to do, is really pathetic. Ayers and Dohrn would do well to come out and say they were wrong, that they misled a lot of good people down a destructive road, that they share blame for the deaths in the townhouse and for the fear they caused countless other innocents, and move on. No one needs their yearly commemorations and celebrations of Weatherism.

I highly praise the authors for their activist work from the 1960s on. Some say privatizing property itself is commiting violence against the poor who then can’t get access to land for food or clean water to drink. Their destruction of property was merely the final untried tactic to stop the war. As they and Kirkpatrick Sale noted in his book SDS, many acted in cooroboration. I only feel they made a mistake in being duped by the CIA’s MK-ULTRA, as so many young leftists continue to be. It hurt their reasoning ability enough to laud Manson. I hope new SDS learns from the mistake of the lure of mind damaging psychedellics (See Martin Lee’s Acid Dreams for examples).

When Ayers finally shows the courage to admit, as has Mark Rudd, that his actions were more than mistaken, that they harmed and held back the Vietnam antiwar movement, he will at last have the credibility to comment honestly on these historical events.

Whatever we did; it was not enough. But quite possibly nothing we could have done would have been enough. Sds, Weathermen, Pl, RYM, Sojourner Truth Org., Surrealist Group; Yippies, pacifists…But we were an active force in history, neither bystanders nor victims…Like the abolitionist movement and the IWW, we leave a heritage of struggle and courage …what more can anyone do?

A delicate issue, indeed. And in a foreign language..Ooops!

To one side, “20 acts over its entire existence, and no one killed or harmed ”

To the other side, the Vietnam war and a “legal” gouvernemental terrorism abroad and at home.

I’m a nonviolent person. Non violence is only believable if it condemns first the roots and the causes of violence. But I refuse to condemn “violence” . Violence is celebrated through the world by all the nations (in France with a march past for the Bastille Day and through the national anthem ) Violence manage the relations between nations. Violence is legal and institutonalized on the one side, criminalized on the other side (revolutionary violence)

“Violence begets violence” is a historic nonsense .(civil rights movement). In French, we say “I refuse to yell with the wolves “.

Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn made a choice, probably not mine, but they have my sympathy (Mark Rudd, too) and they are accepting responsability for their choice, in their own right. They are a part of this heritage of struggle and courage

Penelope, nice to read you.

LeisureGuy,

Do you recall what kind of bombs John McCain and his buddies were dropping on the Southeast Asian population?

Bill Ayers and Bernadine Dohrn’s commentary on the 40th Anniversary of the Weathermen town house explosion demands a reply.

We should of course mourn for ALL the dead in a war, and that includes the three Weathermen who accidentally blew themselves up in the NYC townhouse explosion 40 years ago. But there is more that needs to be said, and Ayers and Dohrn fail to say it.

The March 1970 explosion in NYC was the accidental setting off

of a bomb intended to be used at an enlisted men’s dance

at Fort Dix, New Jersey. That was part of the twisted politics

of the infantile ultra-left group “Weathermen,” largely comprised of sons and daughters of very wealthy Americans.

Ayers and Dohrn reflect on the frustration shared by all antiwar activists of the era, but offer no apology for the stupidity of their

own politics, which clearly were detrimental to the entire antiwar movement.

Had that Weatherman bomb not exploded prematurely, had that bomb reached its intended target, killing and maiming GIs in New Jersey, I shudder to think of the impact on the antiwar movement. History shows very clearly that it was the GI and Veterans antiwar movement, dissent in the military organized and supported by both soldiers and civilians, that helped our success in bringing the war to an end more than anything else apart from the heroic resistance of Vietnam itself.

What would have happened to the efforts of activists inside and outside the military had the Weathermen’s effort succeeded? What would have happened to the antiwar coffeehouses near US bases throughout the US, in Asia and Europe? Or to the scores of GI underground antiwar newspapers circulating at bases around the world? How would our ability to recruit GI’s to the antiwar cause have been affected?

How would the May 1971 VVAW Dewey Canyon II action in Washington DC, a true turning point for our country and for the American people, have ensued, had that Fort Dix soldiers’ dance been bombed months earlier?

The answers, I fear, are obvious.

Mark Rudd, another Weathermen leader of the era, in his new book “Underground” offers an explicit apology for the stupid and destructive politics of the Weathermen. Ayers and Dohrn have not. They have an obligation to do so.

These are historical realities forty years old. Nominally we might give it all a pass. But we see sometimes today the rise of frustration in young anti-war activists as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan go on seemingly endlessly. And we see, occasionally, (e.g. among a number of folks at the RNC demonstrations not long ago), the romanticization of ultra-leftism. So history is important after all and we need young people to understand the grievous errors of adventurism of forty years ago.

Andy Berman

US Army, 1971-73

Veterans for Peace, Chapter 27

Whatever we did; it was not enough. But quite possibly nothing we could have done would have been enough. SDS, Weathermen, PL, RYM, Sojurner Truth, Surrealist group, Yippies, pacifists….But we were an active force in history, neither bystanders nor victims….Like the abolitionist movement and the IWW we leave a heritage of struggle and courage…..what more can anyone do.

Penelope Rosemont

No Penelope, we did plenty. We helped the Vietnamese defeat a

mighty empire. Yes, we struggled with tactics and stragegy always.

Sometimes we got it right, buiding a mighty mass movement that touched virtually every sector of American society. And sometimes we got it wrong and were isolated and driven into defeatism.

But in the end, as Vietnamese historians well acknowledge, we provided tremendous solidarity and helped bring the war to an earlier end than otherwise would have happened.

Ayers & Dohrn, two names that should be added to the list of the most evil people in history. Perhaps some future society that cherishes facts and genuine freedom will emerge from the wreck and ruin that this diabolical couple and their comrades have brought upon the United States. Their carefully groomed Kwisatz Haderach Barack Hussein Obama is now at the helm, moving forward with the “fundamental change” he said we could “believe in”; directing his Fedayeen to intensify their jihad and issuing Presidential Directives that rip the Constitution to shreds. When people heard those words “Change We Can Believe In” they thought he meant liberation. But it’s a different kind of liberation these ghouls are bringing. The Tahir Square kind of “liberation”. The “freedom is slavery” kind of “liberation”. They are shepherding a decidedly Islamic/Marxist reversion to the savagery that the U.S. Constitution was designed to prevent. And this Constitution that they all hate – all of them, from the Obamas, to Samantha Powers, to Huma Abadein – this Constitution has protected them at every step along the path towards carnage and destruction. At this point, the Constitution won’t change the situation. The only hope is that a few dedicated individuals who are still in positions of authority will take bold and decisive action, regardless of the cost to themselves, and remove these tyrannical monsters from their thrones. “As the Liberty Lads o’er the sea – bought their freedom, and cheaply, with blood – so we boys, we – will die fighting or live free – and down with all kings but King Lud” (here King Lud should be read as the U.S. Constitution, the basis for genuine liberty and justice).