Part 1: 1838 to 1876

A People’s History of Afghanistan

By Bob Feldman / The Rag Blog / April 23, 2010

[If you’re a Rag Blog reader who wonders how the Pentagon ended up getting stuck “waist deep in the Big Muddy” in Afghanistan (to paraphrase a 1960s Pete Seeger song) — and still can’t understand, “what are we fighting for?” (to paraphrase a 1960s Country Joe McDonald song) — this 15-part “People’s History of Afghanistan” might help you debate more effectively those folks who still don’t oppose the planned June 2010 U.S. military escalation in Afghanistan?]

The number of U.S. combat troops in Afghanistan has increased from 51,000 to between 70,000 and 100,000 since Barack Obama’s inauguration as U.S. president in January 2009. And there are still between 60,000 and 101,000 armed private contractors — as well as 38,000 combat troops in NATO’s International Security Assistance Force [ISAF] from countries other than the USA — in Afghanistan in 2010. Yet if you grew up in the USA , your high school social studies teacher was likely to know more about the history of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict than about the history of Afghanistan .

But although no people of Jewish religious background lived in Afghanistan prior to the 19th century, by the end of the 1840s (after the Anglo-Indian army of UK imperialism which had invaded Afghanistan in 1838 was driven out by the Afghan people in the early 1840s), about the same number of people of Jewish background then lived in Afghanistan as then lived in the United States. As Raphael Patai noted in her book Tents of Jacob, “the number of Jews in Afghanistan in the mid-nineteenth century was estimated at 40,000.”

But the aim of the UK government’s military occupation of Kabul between 1839 and 1842, during the First Anglo-Afghan War, was mainly to prop up an ineffectual and unpopular leader named Shah Shuja, whom the UK government had put in power, in place of Afghan King Dost Mohammad Khan, as Afghanistan ’s ruler.

UK troops in Afghanistan, however, found the Afghan people to be opposed to their presence there. Between 1839 and 1842, there were “increasingly effective armed attacks on the British garrison” in Kabul, according to Afghanistan: A Modern History by Angelo Rasanayagam.

The UK troops were soon forced to retreat from Kabul to Jalalabad, “through narrow mountain defiles and passes in the harshest wintry conditions, with the long columns of soldiers” and their civilian camp followers “being continuously shot at and ambushed by ferocious Ghilzai tribesmen from the surrounding hills,” according to the same book.

As a result, around 9,500 (including 600 English officers and their families) of the primarily Indian troops of UK imperialism and 12,000 Indian civilian camp followers lost their lives when they were defeated militarily by people in Afghanistan during the 1839-1842 Anglo-Afghan War.

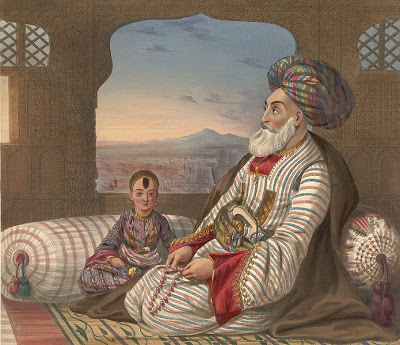

In revenge for being defeated in the First Anglo-Afghan War, however, UK troops returned to Kabul in 1843 and sacked Kabul . But because of its defeat in the 1839-1842 war, the UK government agreed to invite Dost Mohammad Khan to return to Kabul and resume his position as Afghan King. Twelve years later, on March 30, 1855, a treaty of friendship was signed between the UK government and Dost Mohammad’s feudalist government.

The UK government then started to pay King Dost Mohammad an annual subsidy of 10,000 British pounds to help protect its strategic interests in that area of the world. Dost Mohammad remained on the Afghan throne until 1863; and between 1863 and 1878, Dost Mohammad’s son, Sher Ali Khan, was Afghanistan ’s ruling monarch.

After the UK army again intervened in Afghanistan in October 1856 to force the Persian/Iranian government troops that had occupied the city of Herat in western Afghanistan to withdraw, the UK government did not openly intervene in Afghanistan ’s internal affairs until 1876. But as the book Afghanistan: A Modern History noted, “when Disraeli became [UK] prime minister, the tacit policy of non-intervention in the internal affairs of Afghanistan ended, and was replaced by the `forward policy’…”

Next: “A People’s History of Afghanistan — Part 2: 1876 to 1901.”

[Bob Feldman is an East Coast-based writer-activist and a former member of the Columbia SDS Steering Committee of the late 1960s.]

One question: What was the UK’s interest in Afghanistan that brought them to intervene in the first place?

Good question. UK government apparently felt the British Empire’s ability to undemocratically retain control of its India colony might eventually be threatened militarily by Czarist Russia more easily– unless the Afghan government was controlled by a UK puppet ruler like Shah Shuja.

Before he started to receive his annual subsidy from the UK government, Afghan King Dost Mohammad apparently was seen by the UK imperialist government as a ruler who might be willing to act more independently than Shah Shuja and be more willing to make some kind of diplomatic deal with its Czarist Russian imperialist rival that would threaten continued UK government control of India.

Some thoughts from the Grand Old Man.

http://afghancentral.blogspot.com/2010/03/gladstone-on-afghanistan.html