The hidden history of Texas

Part IX: 1890-1920/4 — Oil business emerges; O. Henry publishes

By Bob Feldman / The Rag Blog / February 28, 2012

[This is the fourth section of Part 9 of Bob Feldman’s Rag Blog series on the hidden history of Texas.]

It was during the 1890-1920 historical period that an oil industry first began to develop in Texas. As Randolph Campbell recalled in his book, Gone To Texas, “significant commercial production [in Texas] did not begin until 1894, when well drillers seeking water near Corsicana struck oil instead,” and “production in the Spindletop field [near Beaumont], which reached 17,500,000 barrels in 1902, created the state’s first great oil boom.”

Yet, “in spite of the major discoveries, Texas [still] stood only sixth in the nation in oil production in 1909,” according to the same book. And most people who lived in Texas did not benefit from the development of its oil industry between 1894 and 1920. As Vanity Fair magazine correspondent Bryan Burrough observed in his 2009 book, The Big Rich: The Rise and Fall of the Greatest Texas Oil Fortunes:

If Spindletop created an oil industry for Texas, little of it ended up controlled by Texans. The big money of Spindletop was initially split between groups of powerful Texas businessmen and seasoned oilmen from back east. One Texas faction was an alliance of Austin politicians and Gulf Coast attorneys led by the former governor Jim Hogg, who acquired a valuable lease on Spindletop hill for the bargain price of $180,000 in July 1901, six months after the first gush…

The strange new infrastructure of Texas oil — the storage tanks, the pipelines, the refineries — was controlled by eastern interests… By 1920, two decades after Spindletop, the discovery of oil hadn’t changed Texas much… What oil was pumped from Texas fields was still largely controlled by eastern interests…

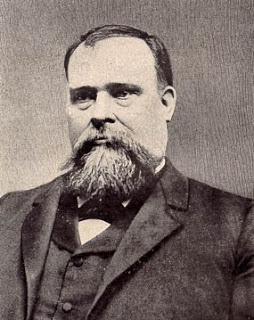

Between 1891 to 1895 Democratic Governor Jim “Boss” Hogg rhetorically “fought against the use of corporate funds in politics, for equalities of taxation, and for the suppression of organized lobbying,” and “demanded steps to make `corporate control of Texas’ impossible,” according to Antonia Juhasz’s 2008 book The Tyranny of Oil.

In the same book Juhasz also recalled that when Hogg was the attorney general of Texas he had written “the nation’s second antitrust law and put it to work against Standard Oil,” and “while governor, he tried to extradite [John D.] Rockefeller from New York to stand trial in Texas.” As a result, “the largely `Standard-free-zone’ established in Texas allowed for independent oil companies, such as Gulf and Texaco, to develop outside of Standard Oil’s grip in what would emerge as the most oil-rich state in the nation.”

According to The Tyranny of Oil, the financing for the drilling in the Spindletop field where oil first gushed out on January 10, 1901, “came from Pittsburgh’s Andrew and Richard Mellon,” and “the Mellon family ultimately forced everyone else out,” before merging the 1901-founded Guffey Petroleum and Gulf Refining oil firms into the Gulf Oil Corporation in 1901.

Financing for the drilling by the Texas Fuel Company (that was founded in 1901 and later changed its name to Texaco) “came from Lewis Lapham of New York, who owned U.S. Leather, the centerpiece of the leather trust, and John Gates, a Chicago financier,” as well as from a New York investment banker named Arnold Schlaet.

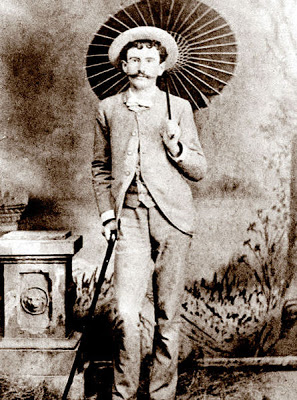

It was also during the 1890s that an Austin writer named William Sydney Porter — who later, under the pen name of O. Henry, became famous in New York City as a writer of short stories with surprise endings — briefly published a weekly newspaper in Austin called The Rolling Stone — over 70 years before Jann Wenner started to publish his Rolling Stone magazine in the Bay Area in the late 1960s.

As University of Auburn Professor Emeritus for American Literature Eugene Current-Garcia noted in his 1993 book O.Henry: A Study of the Short Fiction:

O. Henry and his partner… renamed their paper The Rolling Stone… It was never a commercial success, surviving only a single year with an alleged circulation peak of 1,500, but the fact that O. Henry managed to keep it going at all at times virtually single-handedly — was a remarkable feat in itself. Each week he filled its eight pages with humorous squibs and satirical barbs on persons and events of local interest…

The portable humor sheet quietly rolled off its last issue on Mar. 30 1895, and was soon forgotten until its creator’s worldwide fame a few decades later made of it a collector’s item… For in his… little news-sheet — O. Henry’s first published body of work — lay the foundation stones of his unique short fiction edifice: his themes, plots, methods and style.

[Bob Feldman is an East Coast-based writer-activist and a former member of the Columbia SDS Steering Committee of the late 1960s. Read more articles by Bob Feldman on The Rag Blog.]