Kerrville was a great vision that all of us involved in Texas music shared, but — ironically — one that only someone of Rod’s unique talents as an impresario could actualize.

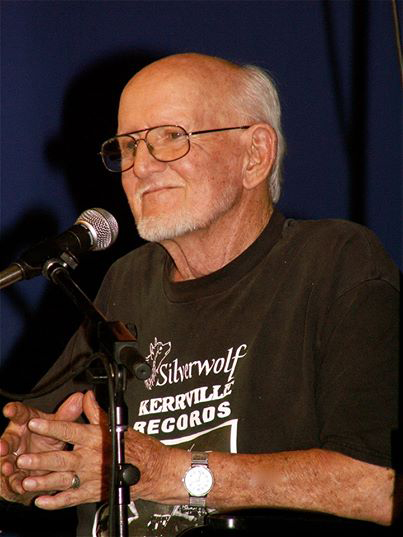

Rod Kennedy, 84, died Monday, April 14, in hospice care in Kerrville, Texas. Kennedy founded the Kerrville Folk Festival in 1972 and, as the Austin Chronicle wrote, “managed to grow his tiny festival into one of the behemoths of the industry, an annual 18-day event that predates most modern music festivals…” Renowned singer/songwriter, author, actor, and playwright Bobby Bridger was with Kennedy from the beginning and performed at Kerrville for 26 straight years.

HOUSTON — In early March 2014, Dr. Kathleen Hudson of Schreiner University in Kerrville sent me a photo of my old friend Rod Kennedy on Facebook. I contacted her immediately and told her I thought Rod looked like the years were finally catching up with him. She agreed and suggested I try to see him as soon as possible. Kathleen was kind enough to arrange a lecture in her creative writing class for me so that I could have an excuse to be in town and “drop in” on Rod rather than have it appear I was rushing to his deathbed for a final visit.

Immediately upon entering the nursing facility my mind returned to many visits in a similar place to see my mother in her final years. Earlier, I had remembered how much my mother liked Rod because once when he visited my parents, he had asked for a third slice of her chocolate pie. So to prepare for my visit I baked Rod some chocolate cookies. They were a bit burned on the bottom, but I figured he wouldn’t mind. When I arrived an aid escorted me to his room. A bold note on the door ordered “Don’t Let the Cat Out!”

Rod was lying prone on top of the bedspread, sleeping. His breathing was labored. I was shocked because I had not let myself accept how close he was to his final days. Seeing him now removed all doubt about that. I pulled a chair close to the bed and just sat there a while wondering if I should try to stir him or simply leave. I decided that I had to try to speak with him one last time.

He responded slowly with slurred and whispered words to my simple questions about his cat, Tuffy. He never opened his eyes, nor did he rise from his position on the bedspread. But we slowly began to talk about the good ole days and our adventures. He released a tiny chuckle and a grin appeared on his face and he said, “You took me to places I never dreamed I would go.” I said, “And you and created the festival that brought me and my sweet wife Melissa together and now we have our fine young man Gabriel.”

My relationship with Rod Kennedy was complex to say the least.

I reminded him of the treats I brought and I helped him nibble on a cookie as we struggled through a few more moments of whispered reminiscences. I could tell he was using more energy than I wanted to take from him, so I just shut up and let the quiet come back over the room. As I looked at my old friend in his last days on earth I was flooded with memories and drove back my sadness with the realization that few men have lived the life Rod Kennedy enjoyed. He had actualized his great vision, and brought something truly wonderful to life that will last will into the century — if not forever. And it is true that Melissa and I met and married at Kerrville and for that alone I would forever be in his debt.

Soon his protégée, Dalis Allen, entered the room and we chatted a bit about his status and visited about the festival and I left with tears in my eyes. I knew then I was going to write something about our relationship, but I figured it would just be more in the order of a private explanation to no one but me.

When Rod passed, people from the media immediately started contacting me to comment about the man and his legacy. When Thorne Dreyer asked me to write something about Rod for The Rag Blog, however, my first impulse was to decline; it felt too personal and too soon. And when considering talking about people I always remember my father’s admonition, “when you point your finger at someone always remember that three are pointing back at yourself.”

But there is also the matter that my relationship with Rod Kennedy was complex to say the least. So after thinking about it a while, I realized I was one of the folks who had been there all along and, as such, I had to open up a bit about my history with him. Faced with having to condense four decades into a few words, I decided to structure my essay into four “acts” that would create an overview of important highlights of our relationship.

Act One:

Rod Kennedy Presents

When I stumbled onto the listing Rod Kennedy Presents in the Austin telephone directory in the spring of 1972, I was moving at a very rapid pace. Having begun my professional recording career in Nashville in 1967 with a contract with Fred Foster and Roy Orbison’s Monument Records, I had made enough progress in two years to produce a record of original songs and had begun shopping it in Los Angeles.

While scrambling around Hollywood trying to sell my album, I met author/filmmaker Max Evans and eventually performed the theme song in his feature film, The Wheel. Max asked me to travel to Austin, Texas, for a month to scout the city as a possible debut location for his movie. As soon as I arrived, Austin cast her enchanting spell and like many folks before and after me, I decided to stay.

Soon after relocating to Austin in late 1970, I signed a contract with legendary songwriter Johnny Mercer’s music publishing company, E. H. Morris, and simultaneously RCA Records bought Merging of Our Minds. RCA set a fall 1972 release date for the album and I was soon frequently flying back to Hollywood for multiple remixing of Merging of Our Minds and photography sessions for the packaging.

Since I had already written a lot of jingles and completed a lot of scoring for documentary films at that point in my career, I also started hustling work in my new hometown by lugging a tape recorder the size of a portable television to advertising agencies and independent filmmakers offices and playing a tape of Merging of Our Minds as a sample reel.

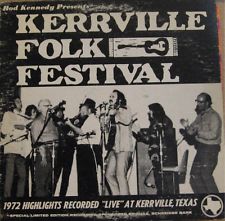

So Rod Kennedy Presents caught my eye in the yellow pages and I called. Rod met me at his offices on North Lamar and I set up my reel-to-reel and played several songs from Merging of Our Minds. He said he loved my songs and informed me that he and Peter Yarrow were producing a folk festival in Kerrville, Texas, in May. He hastened to explain, however, that all the main stage acts for the festival were already booked, but he and Yarrow planned to create a “New Folk” stage as part of the festival.

Since this New Folk stage was specifically designed to celebrate and showcase emerging songwriter performers he said he could offer me a slot on that venue. I had cut my folk music teeth on Peter, Paul and Mary, so I figured this could be a feather in my professional cap and eagerly accepted it.

The main stage performers booked for Kerrville Folk Festival in May of 1972 were Dick Barrett, Alan Wayne Damron, Segle Fry, Steven Fromholz, Carolyn Hester, Bill and Bonnie Hearne, John Lomax, Jr., Mance Lipscomb, Kenneth Threadgill, Michael Murphey, Robert Shaw, and Texas Fever. I was from Louisiana by way of Nashville and Hollywood, but my father’s family had Texas roots seven generations deep. Still, since all of the Kerrville acts were native Texans, I vividly remember feeling like an outsider.

Having been constantly referred to in Nashville and Hollywood as a “folkie,” I found this less-than-cordial Kerrville reception ironic — especially since I already had nearly a decade under my belt as a folk singer before beginning a career in commercial music in Nashville. So my budding career in Nashville and Hollywood seemed to hurt rather than help me at that first Kerrville Folk Festival.

Unaware of my being signed to RCA when he booked me, Rod nevertheless thought it hilarious that the winner of the first “New Folk Showcase” was the only person on the venue with a national recording contract. The irony would prove a harbinger of four decades of incongruent circumstances that punctuated my long relationship with iconic folk music impresario, Rod Kennedy.

But the ironies had already begun during our initial meeting in Rod’s North Lamar office. I assumed since the noted Civil Rights and peace activist Peter Yarrow was involved with the festival that Rod Kennedy — a native Bostonian with an Irish surname — was a liberal with a capital L. I could not have been more wrong.

In those days Rod Kennedy was a fiscal conservative, ‘Bomb the Commies’/John Tower Republican.

I’m certain that Rod Kennedy never had a racist thought in his life. But in those days Rod Kennedy was a fiscal conservative, “Bomb the Commies”/John Tower Republican, a Korean War veteran of the Marine Corps, and a former race-car driver — not exactly your stereotypical “folk singer” cast in the sacred egalitarian mode of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. Rod was also naturally brusque, frequently abrasive, at times cold and stern, and a disciplinarian so strict he made the highway option the preferable route of the “my way or the highway” fork in the road.

Having escaped that kind of thinking in north Louisiana, I was racing as quickly as I could to the other end of the political and spiritual spectrum. So I reckoned that first festival would also be my last. But in the spring of 1973 the great Texas bluesman Mance Lipscomb died just days before the festival and Rod called and offered me Mr. Lipscomb’s slot on the main stage.

I played the Kerrville Folk Festival every year for the next 25 years. Of course this occurred naturally because my relationship with Rod was based on our mutual love of music and the people that create and support it.

But after a couple of years of knowing him, and several minor and major donnybrooks, I grew to understand it was actually our differences that brought us together; our differences brought us to conflict, and our desire and ability to work towards common interests resolved the disagreements.

The first example of our different perspectives came about soon after the move from the Kerrville Auditorium to the Quiet Valley Ranch. I complained in 1974 to Rod that the “New Folk” showcase he and Peter Yarrow envisioned had become much more of a competitive, career-launching springboard to commercial success than the peace, love, and granola hootenanny they envisioned. He fired back, “Well what would you do differently mister smarty-pants?!”

In true counterculture form I suggested we should start the festival with a gathering at the majestic oak tree on the hill.

In true counterculture form I suggested we should start the festival with a gathering at the majestic oak tree on the hill that he and Reverend Charlie Sumners had consecrated for religious services during the festival. I told him I believed that we were all like different colorful songbirds that migrated to Kerrville each year to perform. As such, I suggested that we might form a big circle around that great Texas tree and let everyone sing one song to begin the first day of the festival.

I was working on Part Three of A Ballad of the West at the time so I suggested we call it “The Ballad Tree.” I was in the process of suggesting that we might actually discover talent that way that could be invited to appear on the closing night of the festival when Rod sharply interrupted, “What you are suggesting would quickly become what you say the New Folk showcase is now — a competition. But I do like the idea of a simple song sharing experience. Let me think about this.”

Thus began the “Ballad Tree” at the Kerrville Folk Festival.

Act Two:

Heal in the Wisdom

In January, 1976 the renowned Dakota author/activist Vine Deloria, Jr. introduced me to the whirlwind musical genius David Amram at the legendary Lion’s Head Bar in Greenwich Village. Soon after our introduction Amram suggested we go to his nearby apartment on Christopher Street and play some music. I had no knowledge of Amram’s unique global fame when we met, and while swapping songs during the all-night jam session that followed I suggested he should come down to Texas sometimes and play the Kerrville Folk Festival.

David loved the idea and loaded me down with books, vinyl LPs, and promotional items to take back to Texas. When reviewing the materials in the early morning cab ride to my hotel I learned Amram was the first composer-in-residence of the New York Philharmonic, hand-picked by Leonard Bernstein. Amram also had a career in jazz that would rival his immense talent for classical composition and he had played with the all the masters from “Bird” to Miles, Dizzy to Monk. Immediately after returning to Austin I called Rod and asked him to invite David to come to Kerrville.

“You met David Amram?” Rod exclaimed. I had forgotten that Rod was an avid devotee of classical music and had owned the first classical music radio station in the state of Texas. “Of course we’ll invite him.”

David Amram charmed everyone at Kerrville and was immediately embraced by the ‘Kerrverts’ as the fans and performers had begun calling themselves.

David charmed everyone at Kerrville and was immediately embraced by the “Kerrverts” as the fans — and also the performers — had begun calling themselves. However, in April 1977, David called me nearly in tears. “Rod won’t invite me back.” He complained. “He says he has a policy of only inviting Texas performers back on a yearly basis. Non-Texan performers have to get in line for the next available slot.”

I headed to the ’77 festival with my claws out prepared to fight for David with Rod. We didn’t waste any time and soon were arguing backstage about his strict policies as self-proclaimed “dictator of the festival.” In the middle of the argument he stunned me with a question: “Do you want to be a director of the festival?” I was thrown off-guard and lividly fired back, “that has absolutely nothing to do with our argument about David.”

“It has everything to do with David,” he said. “As a director of the festival you can invite a guest performer every year.”

“So I can invite David next year?

“Yes.”

“What does a director do?”

“Fight with me.”

Two years later, in 1979, I was backstage at the festival teaching a new song to David Amram and John Inmon preparing to go on stage for my set. I thought the song was too long and perhaps John and David could help me decide which verse I should cut. I had come up with the title and major theme of the song by flipping a question I asked in the final line to my song, “The Hawk,” “What will they do when the Earth needs their wisdom to heal?” I called the new song “Heal in the Wisdom.”

Rod came down from his backstage perch to listen to our rehearsal and asked if I wrote that song.

“It’s a new one. We’re going to do it tonight, but I think it needs a verse cut out of it.”

“I want it to be the anthem of the festival.” Rod said as a matter of fact.

“Great!” I replied, “But don’t your think we should play it for the audience first to see how they respond to it?”

“Sure.”

I honestly thought it was only a spur of the moment thing with Rod’s hearing a new song and that would be the last of it. Then Rod walked out on the stage and concluded my introduction with, “Bobby’s new song “Heal in the Wisdom” is now the official anthem of the Kerrville Folk Festival and he’s going to debut it tonight.”

We ended our set with ‘Heal in the Wisdom’ and the audience immediately locked arms, swayed in rhythm and sang along.

We ended our set with “Heal in the Wisdom” and the audience immediately locked arms, swayed in rhythm and sang along. By the third verse they were joining us on stage, singing harmonies like a heavenly choir. That was the night I learned when not to fight with Rod.

Act Three:

Kerrville on the Road

May is a great time for outdoor music festivals in Texas, but May is also a great time for frog-choking, gully-washing rains. Many of the Kerrville Folk Festivals of this era were financial disasters because of the spring rains. There were times when the Medina River and Turtle Creek flash-flooded and literally land-locked festival-goers at Quiet Valley “Island.”

Rod’s conservative nature, his Marine Corps discipline, steel-willed drive, and inherent stubbornness were summoned to survival mode during these difficult years. So many of those of us whose careers were now fast becoming associated with the Kerrville Folk Festival were called upon by Rod to do benefit shows and the fans also responded and dug deep into their pockets simply to keep the gates at the Quiet Valley Ranch open.

Bobby Bridger (from left), Jimmie Dale Gilmore, and Joe Ely sing “Heal in the Wisdom” at Rod Kennedy’s 80th Birthday Celebration at the Paramount Theater in Austin. Photo by Brian Kanof

I think this period created the familial “Welcome Home” aspect of the festival; the producer, the performers, and the fans were forced to unite around the loving spirit the festival created. This situation certainly created the need to reach out to fans throughout the state of Texas.

Perhaps it also simply had to do with Rod’s sentiment for the old big band days and entertainers riding in buses on “package tours,” but the late 70s and early 80s were also the era of “Kerrville on the Road.” Rod would book 10 or 12 single act folk singers like Alan Wayne Damron, Steven Fromholz, Butch Hancock, Shake Russell, Christine Albert, Bill and Bonnie Hearne, Gary P. Nunn, Robert Shaw, Mr. Threadgill, Carolyn Hester, and me, and hire a super band of musicians that could skillfully back each of us. Then, we’d all load onto a chartered bus and travel as far northwest as Amarillo and Lubbock, but more often to Dallas, San Antonio, Houston, and other cities throughout the state.

I can’t recall how many of these tours we did, but these days were some favorites of my long performing career. It was also when I was beginning to really like Rod Kennedy as a person. He was still often insensitive and abrasive, but he was clearly showing signs of mellowing. Moreover, on the long bus rides many of us old hippies were learning to appreciate the fact that the things that we found unpleasant about Rod were the very reasons that the festival we so dearly loved was still in existence.

I think it was also during this time that many of us saw for the first time that Rod’s festival was a great vision that all of us involved in Texas music shared, but — ironically — one that only someone of Rod’s unique talents as an impresario could actualize.

The explosive growth of the Austin music community was rapidly creating a vertically integrated music industry.

The explosive growth of the Austin music community was rapidly creating a vertically integrated music industry in Texas and the Kerrville Folk Festival “family” was becoming one of the most vital spokes in the capital city’s “hub.” By the 1980s the impact of Rod’s vision of a festival celebrating songwriters could be seen blossoming in the careers of talents like Lyle Lovett, Robert Earl Keen, Nancy Griffin, Darden Smith, and scores of other Texas songwriters and musicians.

The Kerrville on the Road experience peaked in 1986 with the “Celebrate Texas” Sesquicentennial Tour that played 20 cities and towns in Texas before departing to Little Rock, New Orleans, Nashville, and the Kennedy Center in DC, Philadelphia, New York and Boston. I think the conclusion of that 1986 tour marked a milestone in the history of the Kerrville Folk Festival. After the completion of that tour the festival’s destiny as an international institution was secure.

Act Four:

A Global Family Reunion

The first time I nearly broke my string of annual performances at the Kerrville Festival was in 1982 when I was at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut, acting and singing in staged readings of Dale Wasserman’s musical Shakespeare and the Indians. In fact, because of the musical I wasn’t actually on the Kerrville bill that year, but I went to Mr. Wasserman and requested permission to leave rehearsals a day early in order to fly to San Antonio and race to Kerrville to surprise Rod and sing “Heal in the Wisdom” the final night.

Throughout the 80s and 90s career opportunities in theater with Shakespeare and the Indians, Black Elk Speaks, and major company productions that A Ballad of the West opened up for me and made it much more difficult to balance my theater career and my career as a folk singer; indeed, in those days I was having a difficult time just getting to be home in Texas as most of my time was spent in airplanes or driving when I wasn’t on stage.

But throughout all this change and motion I remained in regular contact with Rod. Even while I worked on Shakespeare and the Indians and Black Elk Speaks simultaneously I would frequently chat with him on the phone. After he heard me perform “Stages,” the centerpiece song from Shakespeare and the Indians, he would always ask me when Wasserman was going to let me record the song.

When the full company musical of A Ballad of the West toured Yellowstone National Park in 1990 Rod drove to Wyoming and even traveled with our acting company a few days and enjoyed experiencing the show in the spectacular natural settings of the park. He continued to book me on the main stage and the more my career took me away from Austin, the more the Kerrville Folk Festival became for me very much like a family reunion.

At Kerrville I could touch base with what I loved about most about central Texas, the sacred hill country, her people, and her music. I could swim in the Medina River with my old friends. I could enjoy the Kerrville campfires and hear new songs and make new friends. During this era Rod even requested a reading list from me to help him learn about American Indian people past, present, and future.

Several years later he came to me with an idea to produce The Festival of the Eagle to showcase and celebrate contemporary indigenous music. It was a bold undertaking and I’m certain that’s exactly what made him want to attempt it. Unfortunately, there was only one Festival of the Eagle, but it brought my friends Floyd Red Crow Westerman, John Trudell, and JoAnne Shenandoah to Kerrville and their music and spiritualism had a lasting impact on everyone they encountered at the Quiet Valley Ranch.

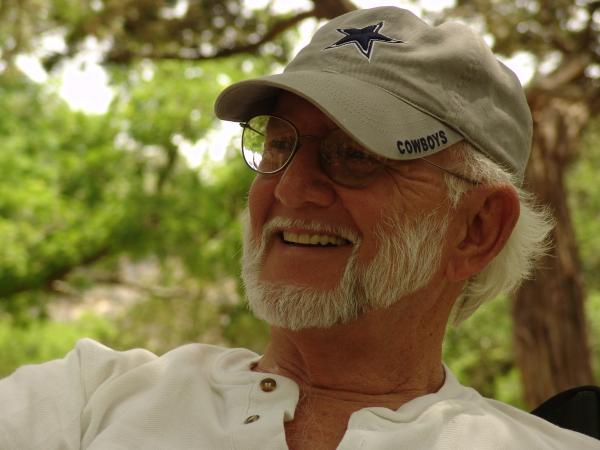

My last quality time with Rod was in 2008 when he and I shared a booth for the entire 16-day run of the festival. He was selling an energy product and I was selling my books, CDs and a new DVD of A Ballad of the West. Sitting in the booth we had a lot of time to just visit with each other and with many old friends who stopped by to chat. It was a sweet time. He was in a great deal of pain with his leg and was using a cane to walk. But he was as feisty as ever.

When he told me with great pride that he had supported Barrack Obama for President I told him that he seemed more comfortable in his liberal persona than he had been in the conservative one.

When he told me with great pride that he had supported Barrack Obama for President I told him that he seemed more comfortable in his liberal persona than he had been in the conservative one. He just laughed. Finally it was clear to me he was neither conservative nor liberal. He was simply a force of nature with a great vision to create a lasting musical festival and he realized he had only one lifetime to accomplish his dream.

Once he was certain that his vision was secure he was ready to depart. He made his transition peacefully in the company of three dear angels, Dalis Allen, Vicki Bell, and Merri Lu Park, old friends who cared for him in his final days and hours. Peter Yarrow and many other folk singers sang him over to the other side. His final words were, “I’m happy.”

Curtain Call

Rod Kennedy is gone now, but he will be with us as long as songwriters gather at Quiet Valley Ranch at what is now America’s longest-running folk music festival.

After completing this essay I told veteran Kerrville musician John Inmon that I had written a tribute to Rod and had focused on how all of us involved with the early days of the Kerrville Festivals would argue with him until we finally reached a friendly compromise. John said that what happened with all of us and Rod at Kerrville was simply an expression of the American way of doing things.

John said, “Think of all the diversity of perspectives and beliefs that clashed and then united around the simple joy of making music. It is wonderful really. What’s more American than that?”

Yes it is, John. Yes, one day together we’ll heal in the wisdom and we’ll understand. Rest in peace Rod.

[Houston-based singer-songwriter Bobby Bridger is also an author, actor, poet, playwright, painter, and historian. He has recorded numerous albums and is the author of four books including A Ballad of the West; Buffalo Bill and Sitting Bull: Inventing the Wild West; and Where the Tall Grass Grows: Becoming Indigenous and the Mythological Legacy of the American West, as well as the epic theatrical trilogy, A Ballad of the West. He composed “Heal in the Wisdom,” the anthem of the Kerrville Folk Festival, ]

Thank you, Bob Bridger, for a beautiful tribute to a remarkable man. Actually, both of you are remarkable. I did not know either of you when I lived in Austin, having left for the north country in 1970 and feeling rather exiled for quite a few years. And for some reason, you did not come to my attention until today. But I am grateful you did and loved hearing “Heal in the Wisdom” for the first time today. It is a lovely song. Thank you, Bobby, and thank you to my brother Thorne for asking you to write this tribute.