Pardon for the Cult of Black Like Me

By Dick J. Reavis / The Rag Blog / May 27, 2008

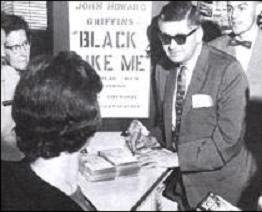

In November, 1959, with the help of doctors and dyes, a white Texan briefly became a black man in Dixie as part of a plan to determine for himself, and to tell others, what the region’s race problem was like. John Howard Griffin’s 1961 account of his six-week undercolor life, Black Like Me, became an American best-seller and in translations, nearly circled the globe.

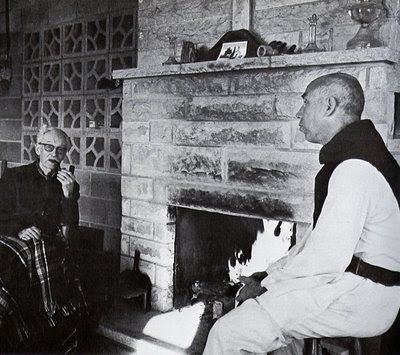

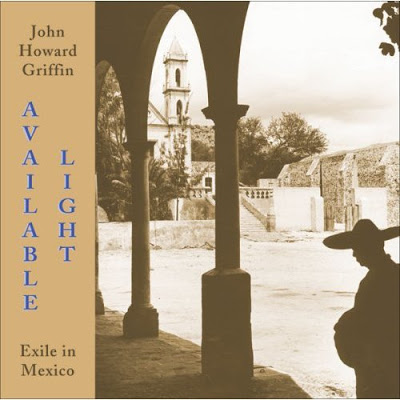

Thanks in part to Wings Press, a smallish San Antonio outfit dedicated to poetry and to multicultural themes, Griffin’s work has enjoyed a steady, if slow revival over the past dozen years. Last published in 1977, Black Like Me was republished in print and audio editions in 1996, 1999, 2003, 2004, and 2006. It has also thrown off companion volumes: a resurrected Griffin novel, a short biography, and now, Available Light, a 117-page Wings Press book of photographs and journal excerpts, tied together by commentary from his biographer, Robert Bonazzi. The photos and excerpts in the book date to 1960-61, when Griffin lived in a Tarascan village near Morelia, Michoacán.

Most of the pictures in Available Light don’t impress my untutored eyes—except for Griffin’s portraits. They are set in darkness; his subjects are revealed through mere spots of light. They are, in effect, negatives of the too-often-imitated white-background images of New Yorker Richard Avedon.

My preference for the portraits, however, squares with Griffin’s own take: Bonazzi cites him as writing, in 1963, that “nothing really interests me in photography except human faces.” Available Light is an addition to the autopsy of Griffin’s virtues, but it’s Black Like Me that will still be on reading lists 20 years from now.

Driving the revival of interest in Griffin and his work are two generations which did not witness the absurdities and brutalities of Jim Crow. Black Like Me catalogs what bygone segregation meant to daily life, especially for job-seekers and travelers.

Driving the revival of interest in Griffin and his work are two generations which did not witness the absurdities and brutalities of Jim Crow. Black Like Me catalogs what bygone segregation meant to daily life, especially for job-seekers and travelers.

Griffin’s writing in the 1961 classic was workmanlike, but not literary. Its lines are stark, muscular and clear, but nothing more: “They called the bus. We filed out into the high-roofed garage and stood in line, the Negroes to the rear, the whites to the front,” is typical of the style.

Griffin’s prose conveyed sincerity and earnestness, virtues in a work devoid of footnotes, statistics, historical references or graphs. He was not out to prove that he was a sage. His message was, “I know that what I write is true because I saw it, heard it, lived it.” By taking a direct, heart-to-heart approach to the racial question of his time and place, Griffin cut through a Gordian knot of disputations that had been nearly fifty years in the making. He did not aspire, as did most journalists of the day, to be a gatekeeper. Instead, he was a guide.

Most of what Griffin did had been done before. In his 1933 Down and Out in Paris and London, George Orwell did for class what Griffin did for race. But nobody had bodily transformed himself for the investigation of racial affairs, and Griffin’s stunt—that he could change his color and pass for black—was a titillation that boosted sales and publicity for his book. How did he accomplish such a thing? Talk show hosts were dying to have him explain.

Sadly, nothing like that book could be funded today. The idea behind it was not PC. Who would believe that a white was more perceptive about the lives of blacks than were blacks themselves? Only whites whose minds were afflicted with doubts about the veracity of blacks! But there were plenty of those, and they made the book a success. Were Black Like Me to be proposed today, it would not be a book, but a “reality series” on TV.

Even in that happier day for print, Griffin’s project was underfinanced. Then a 40-year-old parent and husband in Mansfield, he did not have a publishing contract when he started his sojourn. He made the trip, from Texas to New Orleans, Hattiesburg to Atlanta, in exchange for mere expense money advanced to him by Sepia, a poor man’s Ebony, published in Fort Worth by George Levitan, a white man.

If Griffin got by on slim funding, he worked an even bigger miracle with time. He spent only 42 days in the field for Black Like Me–and only 28 of them “in disguise” as an African-American! The resulting volume is a slim by today’s standards, a mere 63,000 words—but the brevity of his message no doubt added to the book’s appeal.

In later years, Griffin wrote for Ramparts, while it existed, and opposed the Vietnam War, says Bonazzi, a Texas-bred poet who now lives in San Antonio. But Available Light presents excerpts that show Griffin as more conservative than younger radicals of the day.

When Miami Cubans invaded Playa Girón, aka the Bay of Pigs, with American backing in April, 1961, demonstrators in Morelia sacked the offices of an entity called the Mexican-North American Cultural Institute burning its files in the streets. They next turned their glare on Americans who were residing in the region, hoping to harass, uproot or at least embarrass them. Griffin organized the sheltering and defense of his countrymen in the village where he was living, Santa María del Guido, and though few of us would censure that, in the aftermath of the disorders, Bonazzi writes, Griffin met with U.S. embassy personnel—and gave them the names of protest leaders.

Griffin’s opinion of the affair, his journal records, was that “No one in Morelia can now doubt that that this was a plot of international communism—that it was treason committed against Mexico.”

Long live “treason,” if that’s what it was! The government that the demonstrators “betrayed” was in those days a one-party state whose democratic credentials were bracketed by two events: the imprisonment of union leaders Demetrio Vallejo and Valentín Campa, leaders of a 1959 national railway strike, and the Mexican army’s 1962 murder of peasant leader Rubén Jaramillo. Vallejo and Campa were communists, as was Jaramillo and his pregnant wife. I suppose the Jaramillo children, who were also murdered, carried the Bolshevik gene. As Griffin believed, reds no doubt played leading roles in calling Bay of Pigs protests in Morelia, as they probably did across Europe, in China, and even in the supremely menacing Red Republic of North Vietnam.

Bonazzi says that Griffin was not what SDSers called a “CIA liberal,” but a pacifist instead. Fortunately, he didn’t blink, as many in his generation did, when the civil rights movement turned militant as the ‘Sixties came to a close

“For approximately a decade,” he wrote, “black Americans persevered in the dream of non-violent resistance. But its success always depends on the conversion of the hostile white force. … In fact, racists redoubled their efforts in the name of patriotism and Christianity, to suppress not only black people but all non-racists.”

I did not find in the diary excerpts that Bonazzi has variously brought to light that Griffin ever lamented his fate, felt hatred or professed strong regret. In discussing Griffin’s career as a public speaker following the publication of Black Like Me, Bonazzi writes that “He would succeed so well, and with seeming effortlessness, in the public arena because he kept his focus and everyone’s attention on the central issues. Since he never failed at being his own harshest critic, virtually every question asked had been asked over and over in the privacy of conscience.”

The pages of Available Light, and of Bonazzi’s brief biography, The Man in the Mirror, establish that Griffin was a saintly man, a Catholic convert and consort of Merton who, when overwhelmed, sought solace in monasteries. But can it be true that anyone of sound mind has ever been “his own harshest critic”?

But if Bonazzi’s object is to create a cult around Griffin, the raw material is on hand. Griffin, who spent his boyhood in Mansfield, went to high school and began college in France, where briefly worked in the Resistance movement. He enlisted in the Army when he fled home. A combat wound in the Pacific Theater impaired his sight, causing him to go blind in 1947. Griffin penned two novels, married and fathered children despite the handicap. He literally did not see his wife and offspring until ten years after the onset of his blindness, when his vision suddenly returned. His years of darkness probably nurtured the even-handed wisdom he revealed in Black Like Me, and stood at his shoulder for the portraits of Available Light.

Cults, except for those of musical and film stars, are widely frowned upon, but creating one around a guy like Griffin, I’d think, has got to be a forgivable sin.

Available Light: Exile in Mexico by John Howard Griffin, on Amazon.com.

Black Like Me by John Howard Griffin, on Amazon.com.

The Rag Blog