The curious case of the 1960s underground press.

John McMillian, author of Smoking Typewriters, will appear at BookPeople, 603 N. Lamar Blvd, Austin, at 7 p.m., Friday, Feb. 25, 2011, for a reading and signing of his book about the Sixties underground press. John will also be our special guest at a Rag Blog Happy Hour, Friday, Feb. 25, 5-7 p.m., at Maria’s Taco Xpress, 2529 S. Lamar Blvd., Austin. The public is  welcome. And John McMillian will be Thorne Dreyer’s guest on Rag Radio, Friday, March 4, 2011, 2-3 p.m. (CST) on KOOP 91.7FM in Austin, and streamed live on the internet. Listen to the podcast of this show, here.

welcome. And John McMillian will be Thorne Dreyer’s guest on Rag Radio, Friday, March 4, 2011, 2-3 p.m. (CST) on KOOP 91.7FM in Austin, and streamed live on the internet. Listen to the podcast of this show, here.

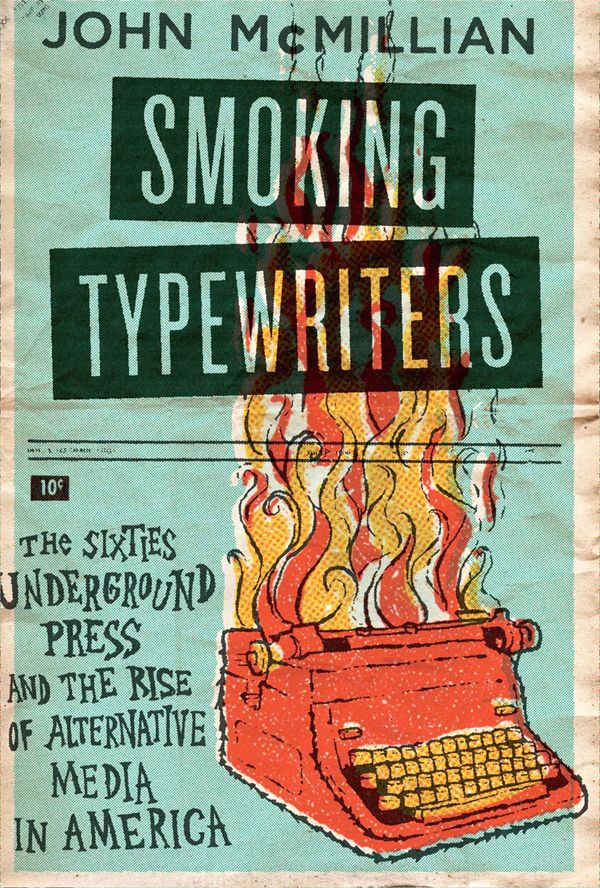

[Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press and the Rise of Alternative Media in America, by John McMillian (Oxford University Press, Feb. 17, 2011); Hardcover; 276 pp.; $27.95]

Art Kunkin was born into a Jewish family in New York in 1928. A brainy kid, he attended Bronx High School of Science, became a follower of Leon Trotsky, moved to Southern California, and recreated himself in the burgeoning bohemian world of Venice.

He would probably not be remembered today and he would certainly not appear in John McMillian’s Smoking Typewriters were it not for the fact that he founded the L.A. Free Press — the Freep — and became one of the curious fathers of the underground newspapers of the 1960s.

McMillian writes about Kunkin and the Freep near the very start of his new book in which he tells his version of the 1960s through the eyes and ears of its loud, colorful, unconventional papers such as the Freep, Rat, The Seed, The Great Speckled Bird, The Barb, The Rag, and many others with equally provocative names.

Smoking Typewriters provides a fast-moving narrative about the birth, the death, and the second life of the newspapers that were spawned by the upheavals of the 1960s and that were also spurred on by those upheavals. Part agitprop in a radical American tradition that went back at least as far as the 1930s, and part agitpop in the unique style of the 1960s, papers such as The Barb, The Seed, and Rat sparked the rebellion of a generation, even as they reported the latest news, gossip, and rumors from the barricades, the communes, the rock concerts, and the on-going spectacle of the streets.

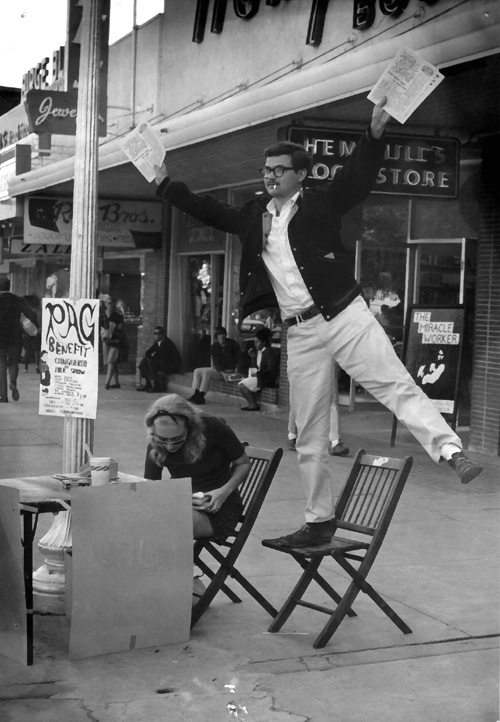

Austin SDS leader George Vizard, later murdered under questionable circumstances, peddles an early issue of The Rag on the Drag near the University of Texas campus in 1966. At left is Mariann Vizard (now Wizard). Image from Smoking Typewriters / Oxford Press.

One of the early papers McMillian discusses in depth is Austin’s Rag, the first underground paper in the South. The Rag, now reborn as The Rag Blog, was a model for many papers that would come later, he says, because it was the first to emerge directly out of a radical community, the first to be run collectively, and the first to merge the hippie and New Left cultures.

McMillian puts readers in the cockpit of the era. He conjures up the radical style, the exuberant mood, and the bravado — no mean feat given the fact that he wasn’t there to live it himself. An historian, he looks back at the era with the benefit of hindsight and with a certain detachment, too, that enables him to tell the story without aiming to grind obvious ideological axes.

He focuses attention on Los Angeles, Austin, and East Lansing, Michigan, as well as on Chicago and New York, and makes it clear that the 1960s as a state of mind and as a way of being in the world, took place everywhere in the United States.

To write his book, McMillian interviewed many of the pivotal figures from that time — both men and women — who wrote for and edited the underground newspapers, such as Harvey Wasserman, Allen Young, John Holmstrom, Thorne Dreyer, Alice Embree, Ray Mungo, Sheila Ryan, and others. In Smoking Typewriters he looks at the sexual politics of the papers, and at the tangled, complex relationships between men and women as they played themselves out in newspaper offices.

Smoking Typewriters takes readers from the early days of SDS, through the rise of the anti-war movement, to the Rolling Stones concert at Altamont in 1969 that has often been described as the culminating event of the decade. Ten pages of photos from the 1960s put faces to the names mentioned in the book.

There’s a brief last chapter that looks at trends in alternative media since 1969, and an afterward that touches on zines, blogs, and bloggers, and in which McMillian predicts that, “we are going to see a collapsing of private space and a diffusion of power around knowledge and information.” For those who would like to dig deeper into the subject, there’s also an extensive bibliography and more than 50-pages of footnotes

The most controversial aspect of the book from my point-of-view as a writer for the underground press and as a contributor to Liberation News Service (LNS) is McMillian’s privileging of SDS and the New Left. SDS was obviously influential; New Leftists changed life on college campuses. I was an SDS member and a New Leftist myself. But I was also a hippie, and a member of the counterculture, and from where I stood the underground newspapers were as much a product of the hippie counterculture as they were of SDS and the New Left.

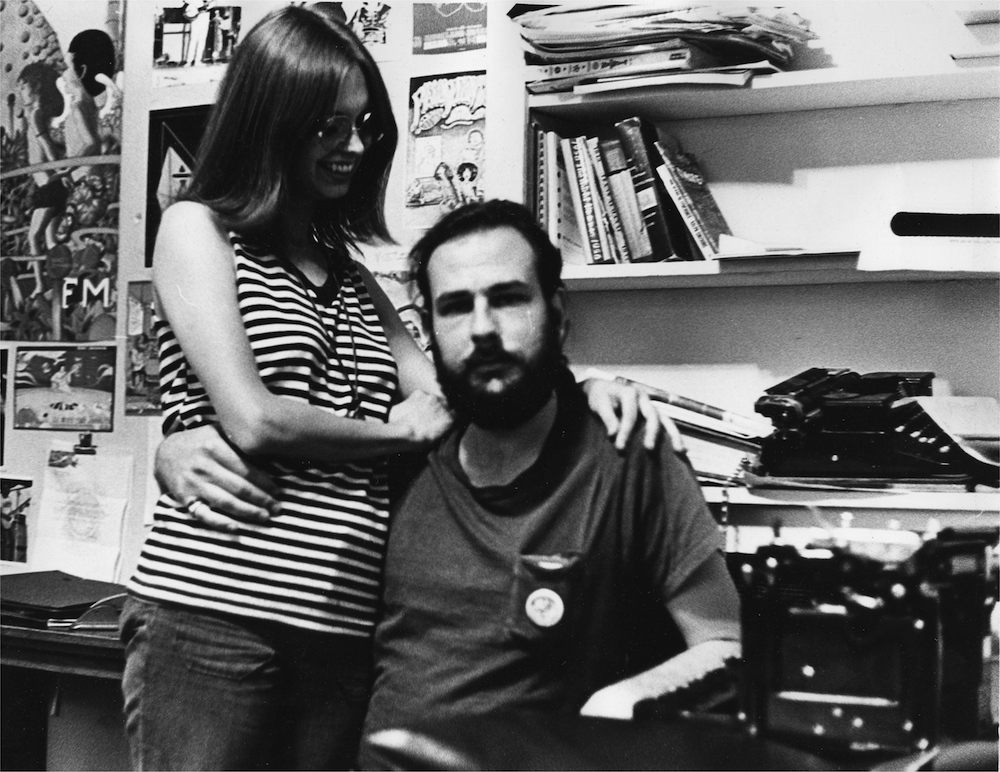

Thorne Dreyer, now editor of The Rag Blog, and the late Victoria Smith, shown at the offices of Space City! in Houston in 1970. Image from Smoking Typewriters, / Oxford Press.

McMillian gives more emphasis to the overtly political figures of the era, and to the ideological nature of the papers, and minimizes aspects of the cultural revolution of the 1960s. In some ways, the evidence provided in the book goes counter to McMillian’s own argument. So, for example, he offers a pithy quotation from Abbie Hoffman, one of the founders of the Yippies, who said of the underground press, “It is a visible manifestation of an alternative culture. It helps to create a national identity.”

Granted, McMillian discusses nomenclature such as “New Left,” “hippies,” and “politicos” in the introduction to his book. He might have taken the discussion to a deeper level and provided more insight. Still, his book will be appreciated by both ex-New Leftists and ex-hippies because it looks again at the push and pull that took place between those who followed Marx, Mao, and Lenin, and those who followed Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg, and the Beatles.

Moreover, as McMillian recognizes, there was no clear-cut schism between the hippies and the politicos. So, for example, he offers a useful comment about those two seminal 1960s figures, Marshall Bloom and Ray Mungo, the founders of LNS: “They were a curious duo, dope smoking, hip, full of far-out incredulousness, yet terribly concerned about Vietnam, the urban crisis and politics.”

In the 1960s, we were all — if I may speak for a whole generation — very curious in the sense that we were an odd and unpredictable mix of cultures, values, and identities, especially in the eyes of the Joneses who just couldn’t keep up. As Bob Dylan put it, “something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, do you Mr. Jones?”

The writers for the underground press, as McMillian shows, not only knew what was happening, but also provided maps and blueprints for others who wanted to join the happenings, the be-ins, the love-ins, the sit-ins, and the whole spectacle of the cultural revolution.

[Jonah Raskin is the author of For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman, and Out of the Whale: Growing up in the American Left. He teaches at Sonoma State University.

- Also see Anis Shivani’s excellent review from the Feb. 20, 2011, Austin American Statesman: Pressing for change: John McMillian’s ‘Smoking Typewriters’ charts history of underground newspapers.

I’ve not read McMillian’s book, so assuming the accuracy of Raskin’s review, the differences among the 1960s “alternative” press have been glossed over. For instance, there is no mention in the review of the Berkeley Tribe, only the Barb, which was a paper with a commercial purpose. There are other examples of papers which sought to profit from, rather than promote, a genuine counterculture.

Jay — In his book, McMillian discusses the Berkeley Tribe, describing how its coverage of Altamont from the inside differed from that of the clueless establishment media (as we called it then).

And he definitely distinguishes between the papers that became commercially-driven, like the LA Free Press, and those that were part of the movement community, and were unconcerned about (and incapable of!) making a profit, like The Rag.

Sadly, there were few if any alternative papers that managed to combine commercial viability with integrity, at least not for long.

However, Austin and the Rag were blessed with a supportive community, of which I would single out today Oat Willie's, a steadfast advertiser through good times and bad. There were many others, but it's interesting to note that Oat's is now one of the

Positive, soulful comment, Mariann — thanks. However I think you mean the Village Voice, not the East Village Other, which ceased to exist a long time ago. The Village Voice, founded in 1955 I believe, is now part of a very corporate chain of so-called alternative newsweeklies.

Fine review, Jonah. Thank you. I just reviewed John's big, fun, romping tome for High Times. Our

Thorne and Mariann,

Thank you. You cleared up a substantial amount of my concern. I should read the book, and probably will sometime. For several years I had a subscription to the Guardian, which as I'm sure you recall was much more political than cultural, and to the Great Speckled Bird, out of Atlanta, which was both.

I didn't subscribe to The Rag (if The Rag