Underground, Again

Underground, Again

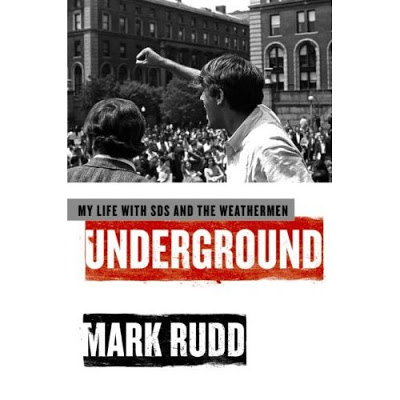

Mark Rudd’s ‘Underground: My Life with SDS and the Weathermen’

A charismatic individual with very little sustained radical organizing, he came out of nowhere at a crucial moment in the 1960s and was instantly catapulted into the national spotlight.

By Jonah Raskin / The Rag Blog / March 30, 2009

[Underground: My Life with SDS and the Weathermen, by Mark Rudd, published by William Morrow, March 24, 2009.]

In the beginning was the underground. Indeed, the “underground” as a form of resistance to established power is a thread that runs through the centuries. Specific, historical undergrounds have existed whenever and wherever “the state” has existed. If there are police, prisons and judges, there will be undergrounds – oppositions that are clandestine, and invisible. It’s in the nature of human beings the world over to form secret organizations, and networks aimed at sabotaging the structures of society: the military, the work place, the church, and the family.

Ironically, the 1960s was an era in which the concept and the practice of the underground thrived, even as a generation of hippies, freaks, misfits, Yippies, feminists, Black Panthers, radicals, and non-conformists came into the open, took to the streets, and went naked both literally and figuratively. It wasn’t until the 1970s, which, one might argue is when “the 1960s” really happened, that political undergrounds – such as the Weather Underground, and the Symbionese Liberation Army – were born. About those two groups there has been almost uninterrupted fascination. There have been dozens of books and movies about them: Patty Hearst, Bernardine Dohrn, Bill Ayers, and the SLA members.

In the 1960s and 1970s, I wrote for underground newspapers, like The Seed and The Liberated Guardian, and worked for Liberation News Service. I was also affiliated with the Weather Underground; my wife, Eleanor Raskin, was part of the underground. I wrote most of “New Morning,” a communiqué from the Weather Underground, and I also aided and abetted — to use the legal terminology — Abbie Hoffman when he was underground in the 1970s. My own parents had been clandestine members of the Communist Party of the U.S.A. from 1932 to 1948, when they resigned. I grew up with the assumption that going underground was a necessary part of any political movement, and knew that one day I’d go underground, too.

A new book by Mark Rudd entitled Underground: My Life with SDS and the Weathermen, takes yet another look at the underground phenomenon. Mark Rudd was underground for seven years in the 1970s. Previously, he had been a member of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), then a leader of Weatherman, the SDS faction that advocated rioting in the streets, and committing acts of violence, including the detonation of bombs. Though Rudd was underground from 1970 to 1977, and though he had contact with the Weather Underground, he was not a member of the organization, neither as a leader — there was a central committee — nor a follower. The title of the book is ambiguous; a casual reader might look at it and assume that it’s about the Weather Underground. In fact it isn’t.

Like Abbie Hoffman, Mark Rudd wasn’t suited for the underground life – he needed attention, and attention is, of course, the last thing that any fugitive wants. Unless of course, he or she really wants to be caught, and to receive attention.

The Townhouse Explosion of March 1970 which resulted in the deaths of three members of the fledgling Weather Underground so profoundly shook Rudd that he could not be connected to former friends who were now making bombs. He calls them “comrades” but it’s a word that sounds odd coming out of his mouth. True enough, he wants “comrades” but he also wants to be the # One Comrade, which isn’t in the spirit of comradeship at all.

I saw Rudd twice when he was underground and a fugitive wanted by the FBI. The first time, he expressed genuine regret and remorse for the explosion and the death of Ted Gold, Diana Oughton and Terry Robbins. He made it clear to me at that time, in 1970, that he did not believe in the use of violence by revolutionaries in order to achieve political goals. The second time I saw him, in New Haven, Connecticut, he was a silent, anonymous bystander during the demonstrations to protest the trial of Bobby Seale, the founder of the Black Panther Party. In a sense, he was a father of those demonstrations. Protesters were doing what he had been urging students to do for years. But now, he couldn’t take part.

I have seen Rudd several times since he surrendered to the authorities, in New York and in Albuquerque, New Mexico where he lives. He is also in Sam Green’s documentary film, The Weather Underground, which offers far more fiction than fact about the organization. Green’s film has made Rudd’s name and face familiar to today’s radicals. The fact that he was not in fact a member of the Weather Underground makes no difference to them. He’s in the movie, and the movie has replaced the historical record. In the popular mind, Rudd and Weatherman have become nearly synonymous. This book will likely solidify that impression, so ironically the more he insists on his distance from the underground the more he’s linked to it, which enabled him to have all the glamour associated with the underground and to have clean hands at the same time.

Underground: My Life with SDS and Weathermen reflects Rudd’s curious relationship with SDS, Weatherman and the U. S. mass media. A charismatic individual with very little sustained radical organizing, he came out of nowhere at a crucial moment in the 1960s and was instantly catapulted into the national spotlight. In that sense, he is a representative figure of that time when unknown, minor actors on the stage of history briefly became major heroes of the revolution. In 1968 and 1969, Rudd became a spokesperson for the New Left. More accurately, one might say that the news media selected him as to be a spokesperson — and a symbol of youthful rebellion. He went along for the ride, and he tells a lot of that story here.

Rudd did not have a long involvement with 1960s activism. Unlike Tom Hayden and Mario Savio of the Free Speech Movement he did not participate in the Civil Rights Movement in the South, nor did he push SDS to become the anti-imperialist organization it became in the mid-1960s. He wrote no significant political manifesto, such as the Port Huron Statement, and he did not forge any new organization — like the Yippies and the White Panthers. Nor did he create a significant alliance –- like the Venceremos Brigades that brought young Americans to Cuba, though he did go to Cuba in 1968.

Rudd was in the public eye for a brief moment that peaked with the student protests at Columbia in New York in the spring of 1968. From then on he was assured fame, infamy and notoriety. In 1968 and 1969, he was defiant, outrageous, and confrontational. He had Chutzpah. He said “Shit” and “Up Against the Wall, Motherfucker” and he shocked his Ivy League teachers at Columbia. Once the media got hold of him it did not let him go; when he turned himself into law enforcement in 1977 the media descended on him once again, as they had in 1968 and fed him up to the nation.

I read a draft of Rudd’s memoir several years ago, and made suggestions to him, including an idea for the title. I urged him to call his book “Che and Me.” That title seemed to reflect accurately his own sense of grandiosity, and indeed one of the chapters in the early manuscript was entitled “Che and Me.” It is not in this book, alas. Years ago, Rudd also posted essays about himself on his website, and I read them there, too. They were written, he told me, for today’s teenagers, and indeed the language seemed simplified and the ideas rendered cartoon-like.

His new book, Underground, does not sound like the previous iterations of his life. This new account reads as though it was carefully massaged by an editor to make Rudd seem more palatable to readers today. It is written for adults, not children: for aging radicals, not young, irreverent protestors. Rudd also seems to want to make himself appear to be likeable, adorable, and cute. All that time in the 1960s, he now says, when he called people “shithead,” and urged students to smash the state, he was really afraid. Then, he didn’t care who he offended. Now, he says nice things about almost everyone — even Bernardine Dohrn, the leader of the Weather Underground, with whom he has had a running feud — as much personal as political — since 1970.

If this book were to be faithfully adapted for the movies, it would be a long close up of Rudd, with other characters, like his parents, appearing on screen briefly. Rudd would be the star of the show. When it was first published, I didn’t like Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism perhaps because I was too close to the New Left and to the kinds of New Left people — like Kathy Boudin of the Weather Underground — he thought were examples of American narcissism. Now, Rudd strikes me as narcissistic. Lasch was insightful. Underground shows that he’s in love with himself, and with his own image. He has little self-awareness, probably because he’s so caught up in himself and with his image.

In this memoir he tells the story about the time that he and SDS members barged into the offices of Grayson Kirk, the President of Columbia, and made themselves at home there. Kirk had gone home for the day. Rudd describes himself picking up Kirk’s telephone and calling his middle class, apolitical Jewish parents in New Jersey. He wonders now why he did it, and though he offers suggestions, he doesn’t see the obvious — that he was rebelling against his parents — and that he wanted them to know. Lots of us were in rebellion against our parents, including the children of the Old Left. That’s why we spoke of the generation gap.

In this book, Rudd is glib about that telephone call, glib about his parents, and glib about his relationship to them. He wants to be not only Che but Lenny Bruce, too, so he writes of that phone call, “Maybe it was simply that Jewish boys call home, it’s that deeply ingrained.” Maybe it’s this and maybe it’s that. Mark Rudd has that Jewish-American habit of shrugging his shoulders ambiguously and leaving it at that. It could mean this and it could mean that.

Some of the passages from the old manuscript haven’t made it into the new book. Some of the ideas Rudd shared me with, and said he wanted to include, aren’t here, either, like the time his father called him a “schmuck.” Rudd can also be an astute literary critic of the novels of Philip Roth — that other Jewish boy from New Jersey who wanted attention — but his reflections on Roth aren’t here either.

In 1980, when Abbie Hoffman turned himself in to the authorities in New York, I had a conversation with Rudd about Abbie, and Abbie’s need for media attention. I said then that I thought that there’s a basic human need for attention and recognition. Some of us, like Abbie, need it, or think we need it, more than others. Some hardly seem to need it or want it at all. Underground suggests, implies, and shows that Rudd is up there, along with Abbie, near the top of the list of 1960s radicals who wanted attention, and who received far more attention than they needed. Media attention is a dangerous thing. It undid Abbie, and it also helped to undo Rudd. It remains to be seen whether the attention he will receive from the publication of, and from the publicity surrounding, this book about his underground life will undo him once again.

[Jonah Raskin is a prominent author, poet, educator and political activist. His most recent book is The Radical Jack London: Writings on War and Revolution.]

Find Underground: My Life with SDS and the Weathermen by Mark Rudd at amazon.com.

Also see Thomas Good : An Interview With Mark Rudd by Thomas Good / The Rag Blog / March 30, 2009

Professor Raskin seems to be underestimating the importance of Mark’s role in helping to “put SDS on the map” in the late 1960s as the chairman of the Columbia SDS chapter between March 1968 and September 1968, during Mark’s “two good years” (in the words of one still-imprisoned former ’60s New Left activist)of New Left Movement political work.

As I indicate in the “Sundial: Columbia

For a writer so critical of Rudd’s narcissism, Raskin’s review sure has a lot of “I”s in it.

As someone born after 1968 I would have appreciated a little more political analysis and a little less psychoanalysis in this book review. But I haven’t read Rudd’s book so I don’t know– maybe the text lends itself to that.

But even if the movement attracted people with narcisstic personality disorders, as Raskin suggests, pointing that out will only take us so far. I am much more

According to Jonah Raskin, “He [Rudd] wrote no significant political manifesto…” While it’s true he wrote nothing comparable to the Port Huron Statement, Rudd did write a couple fine articles which remain new left classics.

“Keith” has written a thoughtful response to Raskin’s review, including some perspective on today’s revived SDS. This isn’t the time or place to go into why old