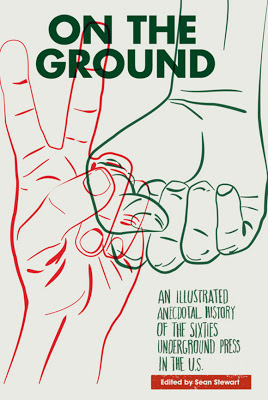

Sean Stewart’s On the Ground is a lively

anecdotal history of the underground press

Amply illustrated with art, cartoons, drawings, and covers from the colorful, eye-catching papers of the Sixties, it comes closer to the spirit of the in-your-face underground papers.

By Jonah Raskin | The Rag Blog | December 14, 2011

[On The Ground: An Illustrated Anecdotal History of the Sixties Underground Press in the U.S., edited by Sean Stewart, preface by Paul Buhle (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2011); Paperback; 204 pages; $20.00.]

Sean Stewart’s On the Ground is the last of three feisty books published in the past year about the Sixties underground press. The strengths of Stewart’s book are spelled out in the subtitle: it’s illustrated and it’s anecdotal.

Unlike John McMillan’s Smoking Typewriters, which came out last winter, and Ken Wachsberger’s Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press, which came out last spring, Stewart’s On the Ground — which has just been published — does not try to be all-inclusive, comprehensive, and analytical.

Amply illustrated with art, cartoons, drawings, and covers from the colorful, eye-catching papers of the Sixties, it comes closer than the previous two books to the spirit of the in-your-face underground papers.

Many of the anecdotes that appear in On the Ground are told by Sixties writers, photographers, and editors who were omitted, neglected, or shunted to the sidelines by McMillan and Wachsberger, though probably not intentionally. There were just too many contributors to the underground papers to include all of them in one book.

Marvin Garson — the editor of the San Francisco Express Times — is mentioned briefly and only in passing. That’s too bad because he had a deep understanding of media, news, and communications. Todd Gitlin mostly dismisses him in The Sixties because he pushed surrealism into “bad taste.” Of course, the underground press was often a mix of surrealism and bad taste.

Paul Krassner — one of the fathers of the underground papers — defended the mix time and time again and refused so say what was fact and what was fiction in his published pieces, what was made up and what was an accurate historical depiction.

The historian, Paul Buhle, provides a preface to Stewart’s On the Ground that has the feel of a hastily written piece that seems designed to attack the competition. In fact, Buhle goes out of his way to target what he sees as the flaws of McMillan’s Smoking Typewriters; his comments probably would have been more useful in a review of that book than in the preface to Stewart’s work.

The historian, Paul Buhle, provides a preface to Stewart’s On the Ground that has the feel of a hastily written piece that seems designed to attack the competition. In fact, Buhle goes out of his way to target what he sees as the flaws of McMillan’s Smoking Typewriters; his comments probably would have been more useful in a review of that book than in the preface to Stewart’s work.

Moreover, Buhle is so partial to the Sixties that he often doesn’t seem to see the creativity and spunk of the subversive newspapers, newsletters, and magazines that were published long before the underground newspapers of the 1960s came along. But Paul Krassner, the founder and long time editor of The Realist, goes back to the 1950s and even further back to Tom Paine and the “whole tradition” of dissenting pamphleteers and makes it clear that America has a long rich history of defiant writers, editors, and publishers.

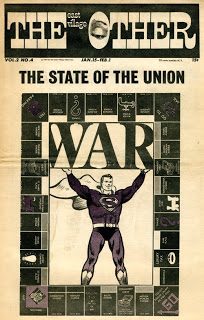

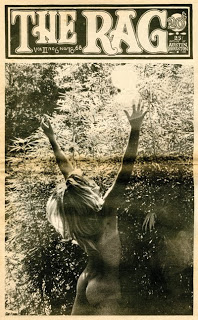

On the Ground does not aim to be critical of the Sixties papers or to skewer the protest movements of the era, but by reproducing the art, the cartoons, and the provocative covers from Rat, The East Village Other, The Seed, Old Mole, Space City!, and more, it aptly illustrates the youthful sexism of the artists and cartoonists and makes all too apparent a generation’s obsession with violence.

Guns, knives, and various assorted weapons appear again and again in more than two dozen illustrations in this book, and from the beginning to the end there are images of naked women, women with conspicuously large breasts, women performing oral sex, and women as the sex toys of men.

Fortunately, the book does not become defensive or try to make excuses for the images that glorify guns and that turn women into objects of male gratification. Enough time has passed, it would seem, for the pictures to speak for themselves, and to reflect the zeitgeist of the era without the need to condemn or defend. There’s something to be said for the passage of time.

Some of the Sixties chauvinism that Buhle exhibits is apparent in anecdotes from activists and organizers such as John Sinclair of the White Panthers who describes Detroit before the 1960s as “a cultural backwater” in which “nothing was happening,” though even in pre-1960s Detroit — and in Cleveland, Buffalo, and elsewhere in the Midwest — there were rumblings, grumblings, beat poets, jazz artists, and Marxists.

Really, folks. The thaw in the cold war and the cracks in the imperial society didn’t show up for the first time in 1960.

The voices of many of the women are less strident now than they were in, say, 1970 in the midst of women’s liberation, when nearly every man was regarded as a male chauvinist pig. Alice Embree gives credit to the civil rights movement that preceded the protests of the 1960s and that provided an “example of moral courage to direct action.”

The voices of many of the women are less strident now than they were in, say, 1970 in the midst of women’s liberation, when nearly every man was regarded as a male chauvinist pig. Alice Embree gives credit to the civil rights movement that preceded the protests of the 1960s and that provided an “example of moral courage to direct action.”

Judy Gumbo Albert, one of the original Yippies, describes her job at the Berkeley Barb in the department of classified sex ads that were usually placed by heterosexual men. “I was a naïve young woman from Canada,” she writes. “This job really opened me to, and made me appreciate the diversity of human sexuality.”

Trina Robbins describes how she “fought her way into the male-dominated world of underground comix” to create her own original work.

Working for the underground press was usually a learning experience, though not always in accord with the ideas about education that were embraced by the college professors of the day. Rat editor Jeff Shero Nightbyrd explains that in New York in the late 1960s and early 1970s, “the Mafia controlled magazine distribution.” The East Village Other tried to bypass the Mafia only to learn that working with the Mafia and not against it was the only way to put papers in the hands of readers. “We had Mafia distributors,” Nightbyrd writes.

Many of the contributors to On The Ground — Thorne Dreyer, Harvey Wasserman, Paul Krassner, Alice Embree, Judy Gumbo Albert, and Jeff Shero Nightbyrd — will be familiar to readers of The Rag Blog, and there are colorful stories about the original Austin Rag, too.

“One of the important things about the underground press was that it was a collective, communal experience,” Thorne Dreyer says. “Everybody came in and got involved and became a part of it, and got politicized through the process.” And that same process, or something very similar to it, is taking place wherever the Occupy Wall Street movement has surfaced all across America.

[Jonah Raskin is the author of For The Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman, and The Radical Jack London. A professor at Sonoma State University, Jonah is a regular contributor to The Rag Blog. Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.]

- Listen to Thorne Dreyer’s August 31, 2010, Rag Radio interview with Sean Stewart, author of On the Ground.

- Read Jonah Raskin’s reviews of Ken Wachsberger’s Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press and John McMillian’s Smoking Typewriters on The Rag Blog.

I am proud to be included in this new book, as in the others mentioned. I’m pleased that new books are helping people remember and learn about the underground press. We had so much fun, and we helped the movements of our era change the lives of many people — mostly for the better. We never called ourselves “progressives,” but we contributed to progress, often with irreverance and humor (not often found in the Old Left publications). Thanks, Jonah, for reviewing these books, and for your own role in the underground press, as well as your important new books, including Field Days and Marijuanaland. My friend Jonah, who turns seventy next month, is one hard-working and smart writer.