Voices From the Other Side:

Keith Bolender’s oral history

of terrorism against Cuba

By Karen Lee Wald / The Rag Blog / April 10, 2011

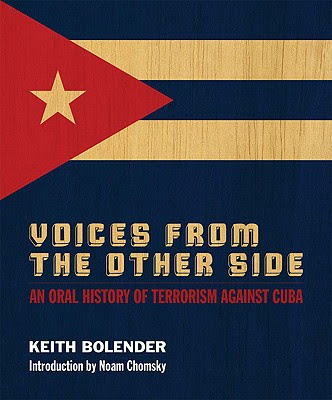

[Voices From the Other Side: An Oral History Of Terrorism Against Cuba by Keith Bolender (Pluto Press, August 15, 2010) Paperback, 224 pp., $21.]

I first learned of Keith Bolender’s book Voices From the Other Side: An Oral History of Terrorism Against Cuba when the author reached out to me after reading an article I’d written on Luis Posada Carriles on The Rag Blog.

The article, “Posada Carriles and the Puppies That Got Away,” was based on an interview with a woman who almost became a victim, along with three children she was caring for, in one of the hotels Posada’s thugs bombed in 1997. The title came from the coded message used by one of Posada’s hired killers in an earlier bombing that destroyed a passenger plane in flight, killing all aboard. The telephone message was “A bus with 73 dogs went over a cliff and all perished.”

Bolender thought I might be interested in his book, an oral history, like mine, taken from many of the survivors of the 50-plus years of terrorism against Cuba waged by the United States and Cuba’s former ruling class.

I was.

I thought it would be helpful if people who are always hearing and reading about the “repression of dissidents” in Cuba and jump to their defense could also hear the other side: what happened to the thousands of people whose lives were affected by the actions of terrorists from inside and outside the country.

I thought it would put a human face on the statistics regarding the material and human damage caused by counterrevolutionaries and mercenaries who are euphemistically called “dissidents” or “anti-Castro militants.”

Voices From the Other Side does this. But it also does a great deal more.

As expected, the first chapter gives an overview of the multiple forms of terrorism carried out against Cuba in what Bolender calls “the unknown war.”

He talks about “the bombs have that destroyed department stores, hotel lobbies, theatres, famous restaurants and bars — people’s lives.” He talks about the first airline bombing in the history of the Western Hemisphere, and also reminds readers of “the explosion aboard a ship in Havana Harbor, killing and injuring hundreds.”

He tells readers about the 1960s attacks on defenseless rural villages and homes, of “teenagers tortured and murdered for teaching farmers to read and write.” He reminds us of the biological terrorism (the dengue fever epidemic) “that caused the deaths of more than 100 children.” And he adds new elements for those of us used to thinking of terrorism solely as shooting and bombing by referring to the “psychological horror that drove thousands of parents to willingly send their children to an unknown fate in a foreign country” (Operation Peter Pan).

This kind of overview has been done before by authors such as Jane Franklin. What Bolender adds here is the lifelong effect terrorist activities have had on the survivors — those left with hearing loss, stitched-up wounds and such, but, even worse, lifelong emotional scars. Survivors who tell of being nervous and jumpy 20, 30 or more years after being in a room where a bomb went off.

And the other kinds of “survivors”: mothers and fathers who for decades mourn the needless deaths of their children; siblings and children of those who were cut up, castrated, and lynched by “anti-Castro militants,” or went screaming to their fiery deaths in an airplane that was already in pieces before it crashed into the sea.

I want these stories to be in the hands of those well-meaning people who ask, “Why does the Castro government repress dissidents?” I want these people to understand what terrorists have done that makes Cubans today so unable to give them the free rein they demand to carry out their actions.

Bolender explains in the very beginning:

Since the earliest days of the revolution, Cuba has been fighting its own war on terrorism. The victims have been overwhelmingly innocent civilians. The accused have been primarily Cuban-American counter-revolutionaries — many allegedly trained, financed and supported by various American government agencies.

And he explains that throughout the island of Cuba “it is hard not to find someone who doesn’t have a story to tell of a relative or friend who has been a victim of terrorism. The personal toll has been calculated at 3,478 dead and 2,099 injured.”

This, of course, is something few on the outside realize, and he talks about why we don’t hear or read about it, about the political/ideological justification for so much cruelty. But he also talks about the real reasons — acknowledged by numerous U.S. administrations — for U.S.-backed and -financed terrorist acts against the island, information that is every bit as important as the humanization of the victims.

Preceded by a well-researched and evocative introduction by Noam Chomsky dealing with the history of and reasons for U.S. policy toward this upstart island nation that would dare to remain outside the grasp of U.S. hegemony, Bolender goes on to give readers a better understanding of Washington’s Machiavellian policies toward Cuba.

He starts off simply, with the well-known fact that “[s]ince the earliest days of Fidel’s victory, America has obsessed over this relatively insignificant third-world country, determined to eliminate the radically different social-economic order” that Castro’s revolution brought about. He describes the various excuses Washington has used since the earliest days of the Republic to justify its attempts to maintain dominance over the island nation.

“America at various times has portrayed Cuba as a helpless woman, a defenceless baby, a child in need of direction, an incompetent freedom fighter, an ignorant farmer, an ignoble ingrate, an ill-bred revolutionary, a viral communist” during the two centuries of the Monroe Doctrine. This history in and of itself is useful for those not already familiar with it.

Where the history gets more interesting is when this researcher uses quotes from U.S. leaders to show both why and how Washington attempted to get rid of Fidel’s revolution:

Richard Nixon, who, Bolender notes, “was one of the first to promote the theme of preventing the revolution from infecting others,” commented in 1962 on the need to “eradicate this cancer in our own hemisphere.” Nixon’s comment reminded me of an explanation offered years ago by a Cuban-American friend of mine, Tony Llanso: “The Cuban Revolution is like crab grass growing in your back yard. You have to pick crab grass because it spreads.”

But it was one particular “how” that I found intriguing. Bolender shows the vicious cycle of increasing repressive measures by the U.S. as Cuba increased its reforms on behalf of the poor majority of its citizens. This quickly — and intentionally — escalated to terrorism on the part of the United States against its tiny but audacious neighbor. And here Bolender is worth quoting at length:

As the rhetoric increased, terrorist acts were formulated and carried out. In partial response to the terror and other hostilities, the revolution became increasingly radicalized.

From the start, policy makers knew terrorism would put a strain politically and economically on the nascent Cuban government, forcing it to use precious resources to protect itself and its citizens. It was to be part of the overarching strategy of making things so bad that the Cubans might rise up and overthrow their government. Terrorism was the dirty piece of the scheme, along with the economic embargo, international isolation and unrelenting approbation.

American officials estimated millions would be spent to develop internal security systems, and State Department officials expected the Cuban government to increase internal surveillance in an attempt to prevent further acts of terrorism. These systems, which restricted civil rights, became easy targets for critics.|

And as most of us have seen, this has been a very successful tactic. Bolender goes on:

CIA officials admitted early on in the war of terrorism that the goal was not the military defeat of Fidel Castro, but to force the regime into applying increased amount of civil restrictions, with the resultant pressures on the Cuban public. This was outlined in a May 1961 agency report stating the objective was to “plan, implement and sustain a program of covert actions designed to exploit the economic, political and psychological vulnerabilities of the Castro regime. It is neither expected nor argued that the successful execution of this covert program will in itself result in the overthrow of the Castro regime,” only to accelerate the “moral and physical disintegration of the Castro government.”

The CIA acknowledged that in response to the terrorist acts the government would be “stepping up internal security controls and defense capabilities.” It was not projected the acts of terror would directly result in Castro’s downfall, (although that was a policy aim) but only to promote the sense of vulnerability among the [populace] and compel the government into increasingly radical steps in order to ensure national security.

In his book Bolender constantly uses direct U.S. sources for his analysis that the terrorism and other aggressive measures against Cuba were designed, at least in part, to force the Cuban government into a “state of siege mentality” that would simultaneously alienate part of the Cuban population, weaken liberal support abroad and serve as an easy target for most U.S. attempts to demonize the Cuban government.

“Former [CIA] Director Richard Helms,” Bolender tells us, “confirmed American strategy when he testified before the United States Senate in 1978; ‘We had task forces that were striking at Cuba constantly. We were attempting to blow up power plants. We were attempting to ruin sugar mills. We were attempting to do all kinds of things in this period. This was a matter of American government policy.’ ”

Most of us who’ve followed Cuba closely have long known the U.S. government did those things. What is more interesting is the “why.”

American experts were hoping the terrorist war would drive the Cuban government to increasingly restrictive security measures; implicit in this was to prove how incapable the regime leaders were. These terrorist acts would not be publicized, recognized nor acknowledged outside of Cuba, so national security policies were portrayed as paranoia, totalitarian and evidence of the repressiveness of Fidel’s regime. To this day the unknown war remains that way…

Here Bolender delves into the psychological warfare aspect of U.S. policy — and its effects:

In the early years Cuban officials faced the problem where they couldn’t tell which citizens supported the revolution, and which were inclined to assist the terrorist organizations or to commit terrorist acts. Everyone was treated as a potential threat.

The consequence, besides the enormous amount of economic resources diverted to combat this war [….] is a society that in the majority has accepted certain civil restrictions in order to ensure domestic security. It is the way the Cuban government has tried to identify the terrorists and to keep its citizens protected. It is the way the government has fought its war on terror.

Bolender reiterates that while the focus of his book is on the victims and their stories, he also wants to show

how these acts of terror changed the psyche of the young revolutionary government, struggling to maintain itself in the face of the destructive actions of its former citizens, directed and financed by the most powerful nation in the world. Traumatized by these acts, this small island nation took drastic steps in the face of constant acts of violence.

Those reactions to the terrorists, and the measures taken to protect the Cuban people, continue to influence national government policies to this day, and have greatly shaped how Cuba is perceived to the outside world. It is the price that has been paid by a society under siege for almost 50 years. A siege in part the result of the hundreds of acts of terrorism.

His analysis goes on to explain that

[t]he key element of Cuban policy against terrorism has been the need of unity for the sake of security, manifesting in a demand for social and political conformity. The consequence has been extensive surveillance systems, arrests for political crimes, a low tolerance for organized criticism or public displays of opposition, suppression of dissidents seen to have accepted material or financial aid from the United States, cases of institutionalized pettiness, travel restrictions, a state controlled press and the rejection of a more pluralistic society.

And we’ve all seen the effectiveness of the tactic that forced Cuba into this position — it’s a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation. The tight control the Cuban government has adopted as a means of survival, Bolender tells us, does in fact destroy much of its liberal support abroad.

The Canadian author still has hope, however. “The termination of American hostility, including the absolute guarantee of the end to any further terrorist attacks from counter-revolutionary exile organizations,” he believes, could “offer the Cuban government the chance to breathe, to manoeuvre without a knife at its throat, as Fidel Castro once remarked, and to attempt to develop Cuban society that was hoped for.”

Put in this context, Bolender’s book achieves far more than the important goal of putting a human face on the victims of terrorist acts and an understanding of why so many of the Cuban people hate the traitors within their midst who work hand in glove with those from Washington, Miami, and New Jersey who fund and carry out these actions. It gives us a new understanding of the psychological warfare the U.S. has been carrying out parallel to its economic and military war.

This is a book that should be in every library and on every progressive bookshelf. I urge people to buy it, read it, pass it on to others.

[Karen Lee Wald, author of Children of Che: Child Care and Education in Cuba (Ramparts Press), has written about Cuba for over four decades, including two from inside Cuba, and continues to regularly visit and report from the island. She circulates a private list, Cuba-Inside-Out, at googlegroups.com. This article was also posted to Truthdig.]

Also see:

- Karen Lee Wald: Posada Carriles and the Puppies That Got Away / The Rag Blog / February 11, 2011.