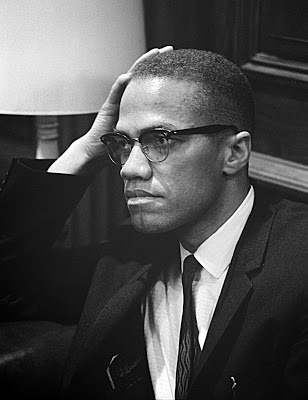

Malcolm X and the right of resistance:

Dr. Marable’s book fills in gaps

but misses on Malcolm’s core vision

By Rick Ayers / The Rag Blog / July 18, 2011

Malcolm X was a towering figure of the 20th century, connecting the wave of Third World revolutions sweeping the globe with the Black Liberation Movement inside the U.S. While the powerful seek to domesticate the man and tame his legacy — a narrow self-help guide or high school lesson on pulling oneself up by the bootstraps — his deeper contribution to the central liberating struggles of our time continues to resonate.

Malcolm X’s life and work was forged in the furnace of a specific historic moment: the old-style colonies were breaking up after the two devastating world wars; India won its independence; China overthrew a pro-western regime; revolutionary battles threw the French out of Algeria and Vietnam; Cuban guerrillas evicted the U.S.-supported dictator Batista.

Vijay Prashad’s powerful analysis of the period, The Darker Nations, documents the rise of the Non-Aligned Nations movement and the creation of the term “Third World” to describe the former colonial and neocolonial regions which wanted to be in neither the Soviet nor the U.S. camps — they wanted independence, freedom from nuclear threat, democratization of the United Nations, and their own locally-grown participatory democracies.

During this same time, the long struggle of African Americans against white supremacy and for basic Constitutional rights and fundamental recognition of their humanity was taking a more militant turn. Malcolm X, first from within the Nation of Islam and later from his own organization, pushed to redefine the terms of the movement — from a petition seeking a way into the U.S. mainstream to a liberation struggle demanding independent power and transformation of the political economy.

Today we forget how far ahead of the wave Malcolm X was, how he created the wave. This is what made him so dangerous to those in power, what drew the attention of the FBI as well as the CIA and various military intelligence agencies.

So many touchstone principles that would soon propel the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party, and dozens of other organizations and movements, were first given clear articulation in the early 60’s by Malcolm X. These included:

- Black pride and “Black is beautiful.”

- The move from a petition for rights to a demand for power.

- The change from seeing African Americans as a minority to recognizing them as part of a majority, the Third World majority, on a global scale.

- The identification of the conditions of African Americans as one of domestic colonialism as well as racial and ethnic discrimination.

- The questioning of the use of nonviolence as the primary tactic for black liberation, encapsulated in the phrases “The ballot or the bullet” and “By any means necessary.”

- The recognition that white people could be and often were a hindrance to the fullest development of Black leadership and the African-American struggle in the South.

- The demand that white people work against racism in their own communities and build solidarity with the Black Liberation Struggle.

- The critique of the Black petty bourgeoisie, which seemed to be making it in America and leaving behind poor and working class African-American communities.

The list goes on and on. While he did not invent or own each of these principles, Malcolm X was the most clear, consistent, and successful popularizer of these views. African-American insights, critique, and inventions have always been major drivers in politics and culture in the U.S. — whether it has been in music, theater, comedy, and literature, or in a the political struggles to enact democracy through elections, economic structures, or education.

The reverberations of Malcolm X’s leadership were felt everywhere, even penetrating the consciousness of this white liberal college student first getting involved and trying hard to understand the world.

I remember being in New York in the summer of 1966, a year after the assassination of Malcolm X. I lived with Charles, an old friend from prep school. We were exploring the city, taking classes, marveling at the explosion of arts, and following the various vibrant political battles everywhere.

In mid-June the front page of The New York Times featured a story on the “March against Fear” in Mississippi which SNCC had mobilized after James Meredith was shot at the beginning of his solo protest against the segregated university. Stokely Carmichael and Willie Ricks dropped a bombshell on the first evening rally, calling for something new to the Civil Rights Movement: Black Power! The marchers had responded with enthusiasm and Black Power became the chant punctuating the march and the Movement itself in that fateful summer.

Black Power had a resonance and meaning that was unmistakable, and it was not about “personal empowerment” or psychological states. It was an enunciation of the anti-colonial struggle of African Americans, a call for political power — by any means necessary. Everything Black activists said afterwards to elaborate and explain the idea was important but the phrase was clear and people knew what it meant. It was Malcolm X’s vision, come to life in the battles of the deep South.

My friend Charles and I diverged right then. He thought the Black Power turn was a disaster: it was reverse racism; it was going to isolate the movement. But I had already been drawn to Che and the Cuban revolution, to James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, and to the Freedom Democratic Party and Fannie Lou Hamer’s articulation of the struggle in 1964.

Many white activists agonized about what it would mean; some who risked their lives for the struggle for justice were hurt when they were asked to leave the South and organize against racism in their own communities. But most got it, had even seen the truth of this analysis in the streets and the meetings. They were pleased, delighted, inspired by the powerful turn that the movement was taking.

Of course, the involvement of us white college kids was a matter of choice but also of privilege. It mainly consisted of reading and discussing. The challenge of the mid-1960’s however plunged us into action. We were no longer just watching a movement; we started building a movement. We were pushed to drop our beneficent and patronizing charity ideas, to think in terms of solidarity.

We began to fight as part of a strategy that recognized the leadership of the Black Liberation Movement and Vietnamese resistance, and the profound transformation of relationships around the world. Did the revolution of the late 60’s and 70’s win? No it did not. But the world would be a much better place if it had.

Dr. Manning Marable’s new biography, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, does much to fill in and correct the historical record. Most agree that Malcolm X’s autobiography, written with Alex Haley, is a powerful organizing document but leaves much out.

Marable offers many beautiful and satisfying moments: the background on Malcolm X’s family and upbringing, the story of the Garvey movement (the United Negro Improvement Association — UNIA) and its strength throughout the U.S. in the teens and 20’s, the descriptions of Malcolm X’s trips to Africa and the Middle East which are much more detailed and impressive than earlier accounts, and the explication of the Muslim Mosque Inc. and the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

But on the fundamental significance of Malcolm X, on his core vision and contribution, Dr. Marable gets it wrong. In the midst of his detailed research, he swipes at the philosophy of Black Nationalism and anti-colonial internationalism. In describing Malcolm X’s historic 1960 debate with civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, he asserts that Rustin won hands down because he proved the “practical impossibility” of setting up a Black state, exposing the “essential weakness” of the nationalist line.

It is one thing to be opposed to Black Nationalism, but to suggest that it is simply an illusory idea with no possible way of being pursued is to mislead. The long history of the struggle for Black Power goes back to Martin Delaney before the Civil War, through the UNIA of Marcus Garvey; it is seen in the work of W.E.B. DuBois and Carter G. Woodson in education; and even in the position of the Communist Party in the 20’s and 30’s which defined a Black nation in the South; the Négritude movement from the Caribbean and Harlem was part of this movement; and it includes many organizations in the 60’s and later, such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) after they embraced Black Power, the Revolutionary Action Movement, the All African Peoples Revolutionary Party, the African People’s Socialist Party, the Republic of New Afrika, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, the Black Panther Party, DRUM, The Deacons for Defense and Justice, the Black Arts Movement, and the explosion of Black Student Unions.

These movements had all kinds of proposals: some for territorial zones inside the U.S., some for reuniting with Africa, and some for independent political identity within an extended presence throughout the U.S. Malcolm X was neither confused nor stumped when confronted with anti-nationalist arguments. His was an internationalist, anti-colonial vision and politics. There is no one else in the U.S. during this historical period who articulated and advanced this insight so powerfully.

Professor Marable argues that reform was possible in the U.S. and that this fact undermined Malcolm X’s position, suggesting that “perhaps blacks could some day become empowered within the existing system.” In order to show that change can come without overthrowing the system, he cites Nixon’s introduction of affirmative action laws.

A look at the condition of African-American people today in relation to educational opportunities and meaningful schools suggests that Malcolm X’s side of the argument was closer to the truth. Marable rejects Malcolm X’s criticism of middle class Black leaders who had supported the election of Lyndon B. Johnson for president. “It apparently did not occur to (Malcolm X),” he asserts, “that great social change usually occurs through small transformations in individual behavior.”

I’m sure it occurred to him but he was part of a much more radical critique, a more far-reaching call for transformation of social relations.

Dr. Marable declares that “‘black nationalism’ was highly problematic in a global context, because it excluded too many ‘true revolutionaries.’” But it’s not problematic at all, any more than Cuban nationalism, Latin American solidarity, Pan-Africanism, Vietnamese nationalism, or anything else that was shaking the world precluded relations between Third World movements.

As in all anti-colonial struggles, Malcolm X asserted the right of resistance and even the importance of African Americans arming themselves. Marable declares that such comments “alienated white and black alike.” But in reality, this is part of what made him so wildly popular.

When Malcolm X says that African Americans should vote but not for Republicans and Democrats, Dr. Marable claims that he “was promoting electoralism but in practical terms gave blacks no effective means to exercise their power. Who were they supposed to vote for if no one on the ballot could bring any real relief?”

The answer is clear: Malcolm X advocated independent political action. That was the only place he believed African Americans could get relief.

The art of writing a political biography is tricky. Two examples that stand out as excellent are Barbara Ransby’s Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision, and Henry Mayer’s All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery.

Each of these does something very important: they situate the focal lives within the movements that produced them and the movements they built. They explicate the positions of the protagonists and appreciate the evolution of their positions — including the debates, experiences, and commitments that made them. And they don’t put themselves in the position of debating with the person they are profiling.

While Manning Marable has made a great contribution with this biography, in some respects he misses the central significance of Malcolm X. The speeches of Malcolm X are available everywhere and should accompany this book, for they animate, explain and consolidate so many experiences and feelings that were boiling beneath the surface at the time.

Malcolm X understood and pursued the implications of the earth-shaking revolutions going on and his words continue to capture the radical imagination of freedom lovers around the world today precisely because he stood for international solidarity and a restructuring of power. It is a vision that still inspires.

[Rick Ayers was co-founder of and lead teacher at the Communication Arts and Sciences small school at Berkeley High School, and is currently Adjunct Professor in Teacher Education at the University of San Francisco. He is author, with his brother William Ayers, of Teaching the Taboo: Courage and Imagination in the Classroom, published by Teachers College Press. He can be reached at rayers@berkeley.edu. He blogs at Rick Ayers, where this article was also posted. Read more articles by Rick Ayers on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Interview with Rick Ayers and Bill Ayers on Rag Radio.]

Well, Marable is certainly following in Malcolm X and Alex Haley’s footsteps in one sense: his book is kicking up some controversy! The extent to which people are still passionate in their opinions of Malcolm is another indication of his importance in our national consciousness.

This is one of those reviews that is more overtly about the reviewer than about the work being reviewed. Example: his attack on the assertion that Bayard Rustin cleaned Malcolm’s plow in a debate is not really to dispute the reported outcome but to point out why, in the author’s opinion, Malcolm should have won.

I guess the author’s prep school was weak on book reviewing skills. As a drop out from public high school, I would not be familiar with prep school offerings.

But this is simply not a well-crafted review in that it says nothing that people considering the book need to know. Well, that’s not quite correct. He places Malcolm’s thought in context…but so does Marable.