FBI snitch was also a sexist, authoritarian, provocative fraud

By Victoria Welle

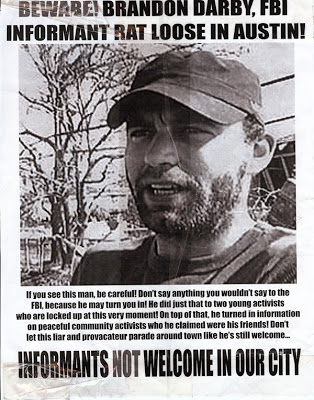

[Victoria Welle worked with Brandon Darby at the Common Ground Collective in New Orleans. Common Ground is a community-run relief organization that played a major role in post-Katrina rebuilding efforts. Darby has since been revealed to have been an FBI informant who allegedly played the part of provocateur in the recent “Texas 2” case in which two defendants were convicted of making and possessing Molotov cocktails at last year’s Republican National Convention in St. Paul, MN. This article was first published at (hasta la) Victoria on May 21, 2009.]

“not sure when you last spoke to [x] or how much she told you about all the common ground drama, but it’s pretty chaotic here, and not in a good way. [a founder] and the fiscal sponsor turned over all directing responsibility of cg to brandon darby, and, well, let’s just say that any lingering notion that common ground is a collective has been completely shattered. darby might be anti-racist, but he’s got a lot to learn as far as male privilege is concerned. there are days when i feel like i’d rather be back working in a formal Catholic institution b/c at least I’d know to expect the blatant sexism and hierarchy. if it wasn’t for all the other amazing folks struggling alongside me with the day to day work i’d be long gone.” — from an email sent [by Victoria Welle] 10 Feb 07

This weekend the public radio show This American Life is going to do a story on Brandon Darby, an activist who became an informant for the FBI. [The story was aired on May 12, 2009, and can be downloaded online.]

I’m very curious to hear how the story gets told, but they probably won’t tell the side of the story I’m most familiar with. I worked with Darby in 2007, when both of us were part of Common Ground, an organization doing relief work in post-Katrina New Orleans.

As the above excerpt from a personal email I sent shows, I have a definite bias, based on my less than positive interactions with him. But my experiences with Darby have also given me a lot to think about when it comes to how we as activists work together, how we hold one another accountable, and how we go about not making the same mistakes as the culture we’re critiquing.

When the rumors of Darby’s involvement with the FBI were confirmed, there was a lot of speculation about when exactly he began informing. Was it just in the months before the 2008 Republican National Convention protests, or did it go back further? Was he working for the feds when he was in New Orleans? It might sound ridiculous and paranoid to consider this, but it’s not hard to see how many came to that conclusion.

Common Ground was political as well as social service oriented, formed in large part to counter the ineffective relief efforts attempted by FEMA and other government agencies. Common Ground routinely criticized government officials (often via an active grassroots media team), it refused any federal funds, and one of its founders was a former Black Panther, an organization that itself saw a great deal of harmful (and deadly) government infiltration throughout its history. Common Ground at that point in time fit the profile of an organization that would likely be under some sort of surveillance.

Then there was Darby’s sometimes erratic behavior and seemingly inexplicable actions that would make more sense if understood as being done to deliberately sabotage the organization. Like ousting two long-term workers simply because they publicly disagreed with him in a meeting. Or, in a burst of anger, canceling the cell phone account used as the central hotline for the hugely successful (and much needed) legal aid program; or the matter of thousands of dollars wasted on an ill-conceived and poorly planned “police accountability” project that went nowhere. Most harmful of all was the loss of many allies in organizations throughout the city who were alienated by Darby’s arrogant bravado and no longer wanted to work with the organization.

All of this said, I think dwelling on the was-he or wasn’t-he questions of when his involvement with the FBI began detracted from the bigger and more difficult questions and issues that we anti-oppression activists need to be focused on. There will always be government interference with our work, and much of that is beyond our control.

The biggest problem I have with Brandon Darby isn’t that he snitched. What still angers me to this day is how his unchecked sexism, authoritarian leadership style, and stubborn refusal to take advice or criticism caused a great deal of disruption to the organization’s relief and justice work in New Orleans. The fact that someone with so much unexamined privilege was able to maintain leadership in our organization as long as he did says a lot about us as well: we as activists have to do a better job of calling out oppressive behavior within our organizing culture.

It means being truly democratic in how we structure ourselves, and being clear that top-down power imbalances are not effective, even if done with supposedly good intentions. It means being willing to have difficult conversations when it’s not convenient, when there’s “not enough time” because we have so much “real” work to do. It means continuing to do our own internal anti-oppression work, especially when it comes to examining the intersection of differing oppressions, and being willing to take constructive criticism.

Common Ground was right to be explicitly anti-racist in its work, but that wasn’t enough. By failing to critically examine and confront other oppressions at work in our organization (such as sexism, ageism, authoritarianism), we allowed highly dysfunctional behavior to go unchecked, which ultimately lessened our ability to do effective work for the people of New Orleans. Sadly, Darby was not the only one at fault when it comes to this lack of critical reflection, and I think this festering of multiple “isms” within the group laid the groundwork for someone as problematic as him to be placed in such an influential position.

Could we have done things differently? Many people in Common Ground had problems with Darby’s actions from the outset, but it was also made clear from early on that disagreement with him would not be tolerated (such as the examples mentioned above). Some long term workers decided to leave the organization rather than continue to work under him. Many of us chose instead to try to work around him, avoiding interactions and further fruitless arguments we felt we could not win with him.

When it was necessary to deal with Darby or one of his (all male) team, I often sent a male co-worker, knowing that he could successfully navigate Darby’s good ol’ boys network. I chose the “easy” way of avoiding conflict by retreating into traditionally female roles: running the office behind the scenes and even (literally) getting coffee for the men when they came by for meetings.

I rationalized my experiences by telling myself that what I was dealing with was minimal compared to what the residents of New Orleans were going through, and my issues needed to take a back seat. But the stress of working in such a dysfunctional setting took its toll on me, and I think I was a less effective relief worker in the long run because of that stress. I’m convinced that many others experienced a similar type of burnout.

If we had dealt more effectively with Darby in New Orleans, would he have been in less of a position of prominence when he returned to Texas, and therefore less able to influence the younger activists who became caught in the web of government surveillance and entrapment? It’s hard to say for sure, and probably not a productive line of reasoning.

What I do know is that we will always be dealing with people like Brandon Darby, and while we are right to be angry about what he did, it can’t detract us from the essential anti-oppression work we each have to do. In the case of Common Ground, making Darby the scapegoat for all that went wrong lets the rest of us off the hook, and distracts us from continuing to ask the hard questions of how each of us is also complicit in oppressive actions.

I’m guessing that if I didn’t have a personal tie to the story, the upcoming episode of This American Life would be, as usual, good radio entertainment. But I have a feeling I’ll instead find myself muttering epithets back at the radio when I hear Darby once again try to portray himself as nothing more than an earnest, ethical activist who couldn’t bear the thought of violence happening, and so he took it upon himself to Do the Right Thing and become an informant. I’ll think back to the behavior I witnessed in New Orleans and wish he’d never been given the mike. Then I hope to turn off the radio and get back to work.

Source / (hasta la) Victoria

Also see James Retherford : Brandon Darby, The Texas 2, and the FBI’s Runaway Informants by James Retherford / The Rag Blog / May 26, 2009

Previous Rag Blog articles on Brandon Darby and the Texas 2:

- Cop Nation : Snitch Brandon Darby, and Riot Police With the ‘Kent State’ Gene by Larry Ray / The Rag Blog / Jan. 8, 2009

- Mariann Wizard on Brandon Darby : ‘To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest’ by Mariann Wizard / The Rag Blog / Jan. 7, 2008

- Brandon Darby : FBI Informant is Provocateur, Not a Hero by Austin Informant Working Group / The Rag Blog / Jan. 6, 2009

- Brandon Darby: Austin Activist Outed as FBI Spy / The Rag Blog / Jan. 2, 2009

Also go to the Support the Texas 2 website.

And listen to “Turncoat,” a story about Brandon Darby on Chicago Public Radio’s “This American Life.”

And, for more background on this issue, read The Spies of Texas by Thorne Dreyer / The Texas Observer / Nov. 17, 2006.

And see the entire “Hamilton Files” of former UT-Austin police chief Allen Hamilton that served as documentation for Dreyer’s story, here.

The Rag Blog / Posted May 26, 2009

I keep reading these Darby stories with an eye to the question “How did he get to be a leader?”

No answers yet.

I remember this obvious provocateur dude named “Duke,” who showed up at the Chuckwagon demo and the next thing I know he’s up there shaking his fist at people I have known for a long time. I mean, from nowhere to publicly shouting down real people…overnight. How can that be?

Well, how did Darby get where he was?

Is the current bench so thin that all you have to do is show up and play?

I’m not saying refuse the services of anybody, but if they don’t have their head on straight should they not have to play right field for a while before they are somewhere they might have to field the ball?

When I showed up at The Rag I did not have my head on straight re sexism. A number of women fixed that, but not by running me off. Basically, I had to change or go hang out with somebody else (it’s a big campus). I’m better off that I changed, and I’m grateful they did not run me off.

But how do these “leaders” just appear? And why aren’t they expected to earn their positions?

Steve — indeed, that is a really good question — and I think some of the answers appear in Welle’s piece:

1) The machismo from which you were so fortunately weaned by strong Ragwomen when you were still young and impressionable is still strong in our society, and the “good old boy” network still exists, even in progressive organizations. In the case of Darby, it is my understanding that he was vouched for by a now-sorely-repentant leader of Common Ground, who regrettably placed loyalty to someone he thought of as a troubled but sincere friend ahead of complaints and warnings from others, such as Welle, who were put off by Darby’s “style”.

2) Welle mentions the urgency of the New Orleans recovery work as one reason that needed conversations were not held. I have several very strong memories of similar postponements during the Vietnam era, when attempts to discuss what were perceived as peripheral issues were contrasted to the daily suffering of the Vietnamese people. The women’s liberation movement indeed was strongly castigated for taking time away from “real” struggle.

The real struggle takes place every day, in our actions and interactions with each other as well as with oppressive authority. When we put off our own freedom, whether (e.g.) from overt male supremecy or more subtle indicators of exclusive male power, whenever we use other peoples’ liberation as an excuse not to confront repressive behaviors in our own lives, we feel the pinch of contradiction.

Steve, I’m surprised you mention your teaching experience at UTSA as introducing you to “free speech areas” — where were you in 1968 when the Regents estalished one next to the ChuckWagon at UT Austin? It had been a patio between the Union and the UGL; people gathered there when M.L. King was murdered, but I don’t recall any other demonstrations there.

Mariann,

Actually my last arrest at UT happened on that very “free speech area.” What I remember about it was that it was roundly ignored by one and all, so I considered it an “attempted free speech area.”

I was arrested not because I was speaking there but because I had showed up late to a gay rights demo and my friend Rick Ream was in handcuffs in the back of a UTPD car on the patio. I jumped up on the car, demanding that they either release him or take me too. They did the latter.

But I was not there because I respected the “free speech area.” I was there because Rick was there.

At UTSA, they took it seriously.

Who of you remember the incident in the 60’s when students were dragged from the UT Student Union by police. There heads bumped down the steps as we onlookers screamed at the police as they took our photographs. What year was that? Why did it happen?

curious

Which time?