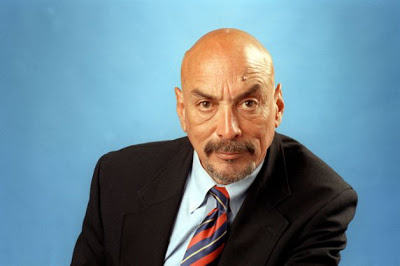

Columnist and Sixties Chicano

activist Carlos Guerra dies

See “Memories from ‘the day’: On the passing of Carlos Guerra,” by Carlos Calbillo / The Rag Blog, Below.

Carlos Guerra, 63, an icon of the Sixties Chicano movement, a former columnist for the San Antonio Express-News, and a leader in social justice issues throughout his life, died December 6, in Port Aransas, Texas.

Arnold Garcia, Jr., wrote in the Austin American-Statesman that Carlos Guerra “was a student activist, grant writer, political organizer, fundraiser, legislative aide, jeweler, opinion writer and a pretty darned good cook.” And, Garcia said, Guerra “was a man whose intellect — like his humor — refused to recognize boundaries.”

Guerra was, according to the Texas Observer’s Melissa Del Bosque, “one of the first prominent Latino columnists in American newspapers,” and was “one of Texas’ most recognizable voices and a role model for countless younger journalists.” In an obituary, the San Antonio Express-News said that Guerra “was an outspoken advocate for increased access to higher education, environmental issues and Latino participation in government and politics.”

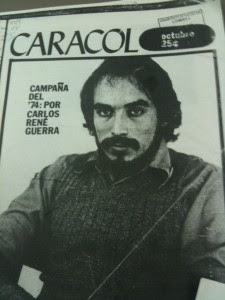

Guerra, who grew up in Robstown, Texas, became an early leader in the Sixties Chicano movement. He was national chairman of the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) and worked with La Raza Unida Party, serving as chairman of Ramsey Muniz’s second race for Texas governor.

At a memorial service for Carlos Guerra December 11 at Palo Alto College in San Antonio, former Raza Unida leader Mario Campeon said, “He stood for the well-being of others, particularly the poor. He fought…the fierce discrimination that existed at that time.” “All of us of that generation had the passion,” said Campeon, “but Carlos was also a gifted speaker in articulating the agenda of the Chicano movement.”

— Thorne Dreyer / The Rag Blog / December 15, 2010

Memories from ‘the day’:

On the passing of Carlos Guerra

By Carlos Calbillo / The Rag Blog / December 15, 2010

The 60’s of course were a different time, and we as thinking young people were being influenced and bombarded by the dominant American culture: the music, the militancy — revolution was in the air — and of course the fashion. We wore bell bottoms, paisley shirts, and desert boots with our serapes and brown berets. We were young and crazy — some of us actually idealistic — trying to find a new way in the reality that was Texas of the times.

This society we perceived as intolerably oppressive and it definitely seemed to us “enlightened” youth to be designed to keep brown and black people down. So we took up “arms” against it, much to the horror of our parents and other “gente decente,” such as LULAC and their ilk.

I met Carlos Guerra at some of these early confabs of the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO), and since the Houston MAYO cadres were urban and “hippie-ish,” many of us either didn’t speak Spanish or did so haltingly. When I began to attend MAYO actions in the small communities across South Texas (small compared to Houston) and discovered that some of the MAYO hermanos/hermanas spoke mostly Spanish, perhaps out of nationalistic zeal, I — and many of the Houston MAYOs — would become uncomfortable.

One time we traveled to Robstown, Texas, to support a rally protesting the racist school system, which of course was designed not to educate our people, but to serve as an institutional bludgeon to keep us Mexicans down and ignorant. Robstown was a perfect example of a small Texas town where the population was overwhelmingly Mexican-American yet the economics and politics were tightly controlled by the gringo establishment.

The rally was being held in front of the MAYO headquarters in a down and out barrio and about 100 community people, parents, and students were there, very pissed, carrying protest signs in English and in Spanish. Robstown MAYO chieftain Mateo Vega was delivering a fiery bilingual speech and rant.

The Robstown police, represented by several big white guys in coats, ties, and sunglasses — and wearing very large pistols prominently on their belts — were walking around taking our pictures and generally acting like racist thugs out of central casting.

Carlos Guerra was there of course and afterwards we all met to debrief. I will never forget that, unlike the linguistic ideologues who considered those of us from Houston to be culturally pendejos, he was a firme vato who looked upon us, his urban hermanitos, not with scorn or disgust, but with a loving bemusement — and with an open attitude of inclusion.

Carlos of course was completely tri-lingual and spoke not only English perfectly but also a beautiful Texas Spanish and a stunning pachuco cálo.

From the beginning, Carlos understood the need to unite and not to fight, something that we in the current political arena and climate sometimes appear to forget.

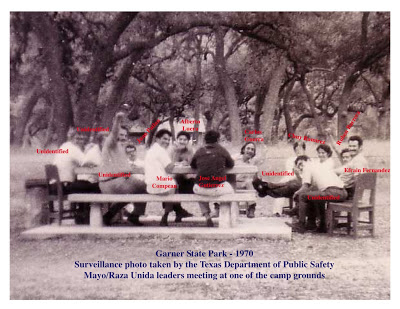

CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Another incident I remember with my friend “Charlie War” — as some of us jokingly called him — was when MAYO and La Raza Unida Party had finally succeeded in taking over Crystal City and surrounding towns, and even entire counties, and Jose Angel Gutierrez called for all chapters to meet and to discuss future strategy at Garner State Park.

It was a beautiful setting with picnic tables under the great oak trees and we munched on barbacoa and tripitas as Jose Angel led us in discussion. We had all noticed several unmarked police vehicles on the periphery and we could see and even hear their cameras — with telephoto lenses — clicking away.

Eventually, Carlos Guerra and several others, including myself, made our way over to the parking lot at Garner where most of us had parked our junky cars. The lot filled suddenly with uniformed DPS troupers who began to berate, intimidate, and bait us in the way that only they knew how to do.

They went around writing down the license plate numbers of all of our cars, which they seemed to know well. Being new to this kind of political intimidation, I freaked out and began to back off. Carlos Guerra fearlessly went up to these PENsadores and began an attempt to educate them on the rights of American citizens to peacefully assemble, our right to meet without fear of governmental interference or intimidation.

Several of these sons of Texas seemed shocked and taken aback that their “right” to harass us was being challenged by this long-haired hippie who seemed not to fear them or anything else for that matter. They became very upset but apparently couldn’t come up with an excuse to arrest Carlos in front of witnesses; they muttered something and left.

Every time we visited Robstown, Carlos was there ready to assist us, his urban MAYO brothers and sisters, with a meal or with a place to crash. There have been many — and will be many more — remembrances of Carlos Guerra, incredible tales, profound and funny adventures, many of them even true. For those of us who were touched by his life, it goes without saying that we, and I for one, will never forget his wit, his love, and his example.

To paraphrase the bard (some vato from Inglatierra): “He was a man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again.”

Amen y con safos. Descanse en paz, hermanito en una raza que pronto llegará a ser verdaderamente unida, porque si se puede…

[Carlos Calbillo is a filmmaking instructor and filmmaker living and working in his hometown of Houston, Texas. He is currently working on a documentary film on emerging Latino political power in Houston and Texas. He can be reached at laszlomurdock@hotmail.com]

Hey Carlos. How about some more Texas History? And how do you get the surveillance photos?

Dee Brown