Tommy Smothers: ‘I dedicate this Emmy to all people who feel compelled to speak out, not afraid to speak to power, won’t shut up and refuse to be silent.’

By Joel Selvin / October 22, 2008

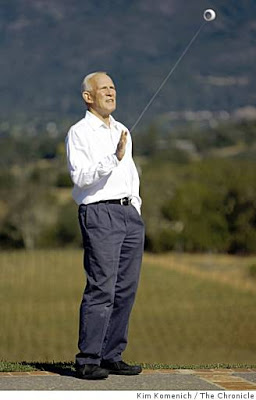

“No comedian’s wife thinks he’s funny,” Tommy Smothers says as he surveys the panoramic vista from his hilltop home and vineyard in the middle of Sonoma’s Valley of the Moon. “The first few years of the marriage, maybe. I was funny as hell the first couple of years.”

Smothers first repaired to this peak 40 years ago to lick his wounds after CBS abruptly pulled the rug out from under the top-rated “Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour” on the eve of its fourth season, the culmination of constant harassment and surveillance by the network’s censors during the show’s three seasons.

At last month’s Emmy Awards, Smothers accepted a belated trophy for his contributions to the team that won the 1968 writing award for the show’s final season; Smothers left his name off at the time, fearing the inclusion would draw controversy. When he accepted his Emmy last month, he was typically plainspoken and eloquent at the same time, a Smothers hallmark. (The speech is on YouTube.)

“Freedom of expression and freedom of speech aren’t really important,” he told the audience, “unless they’re heard. The freedom of hearing is as important as the freedom of speaking. It’s hard for me to stay silent when I keep hearing that peace is only attainable through war. There’s nothing more scary than watching ignorance in action. So I dedicate this Emmy to all people who feel compelled to speak out, not afraid to speak to power, won’t shut up and refuse to be silent.”

September was a watershed moment for the Smothers Brothers in another respect: The long-awaited release of the comedy show’s third and final season on DVD, this time including the portions of the show CBS censored, including Harry Belafonte singing “Don’t Stop the Carnival” as footage of violence outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago rolled behind him.

NPR television critic David Bianculli will publish his oral history of the Smothers Brothers show next year. What started as a last-ditch effort by the network to salvage TV’s dying variety-show format became a landmark series in television history.

Act of repression

The muzzling of the Smothers Brothers at the height of the Vietnam War and the era of student protest was an emblematic act of political repression three months after Richard Nixon was elected president. But the firing of the Smothers Brothers has echoed through the years, becoming a case study in mass media censorship. The brothers, who arrived on the small screen as clean-cut, wholesome folk song parodists, stumbled into the turbulent times.

“Instead of vacuous comedy, we thought, ‘Let’s do something with some bite,’ ” Smothers, says. “There was the Vietnam War, voters’ rights – all sorts of issues that we thought we could reflect and develop a point of view. We didn’t even know it was important until they said ‘You can’t say this.’ Forty years later, people are still talking about it. Isn’t that amazing?”

The Emmy sits on the top of a grand piano cluttered with family photos. Smothers, 71, and his wife of 18 years, Marcy, have two teenagers (Smothers also has a grown son from an earlier marriage). Medical school skeletons, some wearing costumes, are stationed around the spacious living room that looks out over the valley. Smothers sits in a chair next to a table with a pair of lamps shaped like giant kernels of candy corn.

“I had mixed feelings,” he says about the award. “It’s in the past – what’s the difference? Then my wife and kids got excited about it, and I started to think maybe this is pretty cool. I started to think about what am I going to say. Because we were silenced for it 40 years ago doesn’t mean we have been converted. So I made my little statement. Steve Martin introduced me. My brother thought it was cool, pretty neat.”

From the standpoint of today’s TV fare, the old Smothers Brothers shows look decidedly tame. One of the first bits that raised the network’s ire involved nothing more flagrant than comedian David Steinberg saying Moses burned his feet on the bush, and “there are many Old Testament scholars who to this day believe it was the first mention of Christ in the Bible.”

But it wasn’t the lame anti-war jokes or comedian and presidential candidate Pat Paulsen’s editorials on gun control that earned the “Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour” its place in history. “The silencing made it more important, the issue of being censored,” Smothers says. “If they had just not picked up the show, it wouldn’t have been that big an issue.”

Government censorship isn’t necessary in a free-enterprise system, Smothers says, citing reasons that prove he hasn’t mellowed a bit in four decades. “The country doesn’t have to stop people from saying stuff. The corporations do it for them. Look at the Dixie Chicks. The corporations are fighting things for other people. That’s fascism in action. Fascism is when private industry owns the government.”

Developing the act

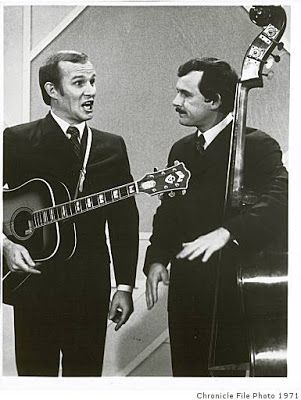

The two brothers (and a sister – Tom, Dick and Sherry) grew up in Southern California. Tommy and Dickie began to develop an act while students at San Jose State, an act they polished at North Beach nightclubs in the ’50s. Their 1961 album, “Live at the Purple Onion,” established them as leading clowns on the folk-music scene. They are celebrating their 50th anniversary in show business and perform as many as 60 concerts a year.

“We were famous before we were good,” Smothers says. “Now we’re good, not famous.”

The act has changed little over the years. Tommy Smothers started playing yo-yo about 25 years ago – when he does yo-yo tricks, they are funny, and when they don’t work, even funnier – and he usually carries one in his pocket.

Tom and Dick Smothers not only mined the fascination of the day with folk songs, but also the passive-aggressive relationship between brothers – “Mom always liked you best” – a role that often spilled over into their offstage life.

“We’ve been 2 feet apart for 50 years. He’s always on my left. I’m always on his right. Same with our baby pictures. We’ve been looking at each other that far away. We’ll get offstage and he’ll look at me and say, ‘When are you going to have that cyst fixed?’ “

Smothers says all that stopped after an 18-hour couples-counseling session about 15 years ago.

The counselor “changed everything basically by saying, ‘Stop the nonsense – you’re professionals, cut out all this brother s-,’ ” Smothers says. “We could fight. We could clear a room.”

Smothers replanted 45 acres on the hillsides surrounding his home after phylloxera took the old grapevines. When he and Dick, 68, first moved to Sonoma and bought property outside Kenwood, they started producing Smothers Brothers Wine, but long ago changed the name to Remick Ridge, after their grandfather.

“People would say Smothers Brothers is a good wine, but it has a funny finish – things like that,” says Smothers.

Dick left Sonoma long ago for Florida, but his older brother has developed a keen appreciation of the role the straight man plays in comedy teams.

“The straight man in vaudeville was paid more than the comic,” he says. “That was the skilled position. The straight man could introduce acts, and you could put him with a funny guy and have him control that. If you don’t believe the straight man, you don’t believe the comic. Look at Bud Abbott, Dean Martin, Dan Rowan. I learned this in 50 years in the business – the quality of the straight man defines how good the act is.”

When he first moved to the property, he lived in a cabana next to the swimming pool and then slowly built a barn, garage and magnificent home over the years. He has grapevines trained to grow along his rooftop, a tomato plant sprawling onto his patio and rosebushes he prunes himself.

The firing clobbered the Smothers Brothers, who spent years recovering their careers and, in many ways, their lives as well.

“It took three years to get my sense of humor back,” he says. “I started taking everything seriously. I became the temporary poster boy for the First Amendment, freedom of speech. Twenty years later, there’s Howard Stern.”

Humor reclaimed

He and his brother went off separately, as Smothers struggled to find himself. “Everything was so serious,” he says. “Then I saw Jane Fonda on the ‘Tonight Show’ one night talking about burning babies. I think Cesar Chavez was on the same show. It was like an epiphany for me – there was no joy, no sense of humor, no laughter. It just turned me around.”

He leaves and returns with a calligraphic print he and his wife sent out some years before as a Christmas card. It is a quote from Alistair Cooke that reads:

“In the best of times, our days are numbered anyway. So it would be a crime against nature for any generation to take the world crisis so solemnly, that it put off enjoying those things for which we were designed in the first place: the opportunity to do good work, to enjoy friends, to fall in love, to hit a ball, and to bounce a baby.”

With a playwright’s timing, his wife arrives, fresh from working out, a trim woman who hosts a radio talk show in Santa Rosa.

“OK, so she’s 25 years younger,” says Smothers. “If she dies, she dies.”

“I didn’t think that was funny the first time,” says his wife.

In Tommy Smothers’ life, everybody else is a straight man.

Source / SFGate

Thanks to Carlos Lowry / The Rag Blog