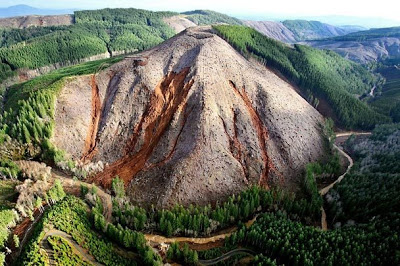

Logging and landslides: What went wrong?

By Hal Bernton and Justin Mayo / July 13, 2008

BOISTFORT VALLEY, Lewis County — When Weyerhaeuser began clear-cutting the Douglas firs on the slopes surrounding Little Mill Creek, local water officials were on edge.

Some of these lands had slid decades ago, after an earlier round of logging. They worried new slides could dump sediments into the mountain stream and overwhelm a treatment plant.

Those fears came true last December when a monster storm barreled in from the Pacific, drenching the mountains around the Chehalis River basin and touching off hundreds of landslides. Little Mill Creek, filled with mud and debris, turned dark like chocolate syrup.

More than three months passed before nearly 3,000 valley residents could drink from their taps again.

“I have never seen anything like this before, and I hope I never do again,” said Fred Hamilton, who works for the Boistfort Valley Water Corp.

State forestry rules empower the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to restrict logging on unstable slopes when landslides could put public resources or public safety at risk.

But in Little Mill Creek and elsewhere in the Upper Chehalis basin, a Seattle Times investigation found that Weyerhaeuser frequently clear-cut on unstable slopes, with scant oversight from the state geologists who are supposed to help watchdog the timber industry.

The December storm triggered more than 730 landslides in the Upper Chehalis basin, according to a state aerial survey. Those slides dumped mud and debris into swollen rivers, helping fuel the floods that slammed houses, barns and farm fields downstream.

A disproportionate number of those landslides started on slopes that had been clear-cut.

The Seattle Times, using information from state aerial surveys, examined 87 of the steepest sites that had been clear-cut. Nearly half of them suffered landslides during the storm. Those sites represented less than 8 percent of the total acreage — both logged and forested — in the Upper Chehalis and its tributary drainages. But the sites produced about 30 percent — 219 — of the landslides.

Among the other findings:

• Weyerhaeuser routinely downgraded slide risks on those sites in logging applications submitted to the state. In watershed plans financed by Weyerhaeuser and approved by the state in 1994, more than half the acreage in the sites was rated at moderate- or high-hazard potential for landslides. But in a second round of site reviews before logging, Weyerhaeuser geologists concluded that most acreage had little or no potential for landslides.

• State forestry officials often noted “unstable slopes” or “unstable soils” in checklists that accompanied their harvest approvals. But there is no record in the files of any field visits by state geologists to scrutinize the logging plans in the 42 sites that later had landslides. Forty of those sites were logged by Weyerhaeuser, two by other companies.

David Montgomery, a University of Washington geomorphology professor who reviewed The Seattle Times’ findings, believes Weyerhaeuser underestimated the risks of clear-cutting.

He notes that several logged areas included features specifically defined in state rules as potentially unstable.

Logging these areas removes trees that help intercept the rain and bind the soil. Decades of studies, which have been used to help shape state forest-practice rules, show logging such slopes can increase the number and size of slides.

Montgomery wrote some of those studies. His blunt assessments of the connection between logging and landslides have sometimes rankled state and industry officials.

“If the policy is not to increase landsliding, then they have no business cutting on some of these slopes,” Montgomery said. “There is not a mechanistic model on this planet that would predict cutting down those trees would do anything other than reduce stability. The only question is how much.”

Catastrophic flooding

The December 2007 flood walloped Lewis County, causing more than $57 million in property damage to homes, farms and businesses. A Seattle Times photo of landslides on a clear-cut mountainside helped ignite a public debate about whether logging practices had worsened the flood’s effects.

Weyerhaeuser and the state Forest Practices Board, which sets state logging rules, are both funding studies to look at the relationship between logging and landslides in the December storm.

In interviews, Weyerhaeuser officials place most of the blame for last year’s landslides on the extraordinary amount of rainfall. Over the decades, they say, the company has made improvements in its forestry practices — some of which were credited in a 2000 report commissioned by the state with helping reduce erosion and landslide risks in the Upper Chehalis. And in some areas, they believe their logging may have made little — or no — difference in the number of landslides.

The Chehalis River’s peak flood flow was more than double the previous record tracked by gauges in place since 1939. Some areas got especially soaked: The Stillman Creek drainage, for example, got 8 inches of rain in 10 hours.

Within the Chehalis River basin, the company said, there were also numerous slides in forested areas, and the company noted such slides may be underreported because they are hard to spot in aerial surveys. By contrast, Weyerhaeuser clear-cuts in other drainages that received less rain had few landslides.

“This storm was so intense that we had no basis for making judgments about what is likely to be stable or unstable. So that is kind of what we are struggling with here,” said Bob Bilby, Weyerhaeuser’s chief environmental scientist.

“At the same time, we are not trying to absolve us of any guilt. … We are mounting a fairly large project to take a look at the procedures we use to deal with unstable slopes.”

The DNR also is reviewing its oversight, according to Lenny Young, manager of the agency’s Forest Practices Division.

In 2001, new rules more strictly defined the kinds of unstable slopes where logging could be limited. In areas that already had watershed plans, such as the Chehalis basin, timber companies were exempted from the new rules, according to Young.

That exemption, which has been in place as Weyerhaeuser clear-cut in the basin, will be re-examined by the Forest Practices Board, said Young. Still, state Lands Commissioner Doug Sutherland, who heads DNR, defends his agency’s enforcement record.

“Do we have enough oversight?” Sutherland said. “With the folks available, with the data available. With the technology available. My answer would be yes, we do. Can we improve it? Definitely.”

Read the rest of it here. / The Seattle Times

For extended coverage, click here.

The Rag Blog

RJ — so — this is in Washington State?

(May seem obvious to many readers, but I have seen similar clear-cut slopes in Oregon…)

Yes, the Chehalis River basin is south of Seattle and Olympia in west-central Washington.