A Promise of Peace:

Colombia, the guerrillas, and the paracos

By Marion Delgado / The Rag Blog / February 20, 2010

Part One: Peace and the FARC

[The phrase “peace process” has been heard throughout the country of Colombia for years. It refers to a way to end the violence, now more than a half century old that, has involved many different groups and many different governments of this war-torn country. This is the first of a three part series from our man in Cartegena, Marion Delgado.]

CARTAGENA DE INDIES, Colombia — In October 1997, in a non-binding ballot accompanying municipal elections, the vast majority of voters — 10 million Colombians in all — voiced support for a peaceful end to Colombia’s conflicts.

That was not the first time that the people of Colombia have voiced their desire for peace. Votes, marches, petitions, commissions, promises; in every way imaginable Colombian citizens have for 60 years, since El Bogotazo of 1948, called for an end to the Bogota government’s war against the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia — Ejército del Pueblo (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia — People’s Army), also known by the acronym of FARC or FARC-EP. This war has killed, and is still killing, hundreds of thousands, and has displaced millions.

This time, their wish got some traction.

After the vote, the people kept up the drumbeat for peace, and the media joined in. Even the ruling class, forgetting for a minute how much the war had benefitted them, joined the outcry. In May 1998, on the one-year anniversary of the murder of two human rights workers, thousands of Colombians took to the streets to demand peace. The peaceful protests were the largest in Bogotá in decades.

1998 was a presidential election year, and on June 15, with popular clamor growing for a peaceful resolution of the conflict, peace became a key issue in Colombia’s presidential campaign. Candidate Andrés Pastrana revealed that his emissary, future High Commissioner for Peace Victor G. Ricardo, had met with FARC leader Manuel Marulanda Velez (alias “Tirofijo,” or “Sureshot”).

Pastrana’s cooptation of the desire for peace worked. He was elected president. By October 1998, one year after the “Vote for Peace,” the government and guerrilla representatives were discussing a FARC proposal to pull all security forces out of five municipalities in southern Colombia, creating a temporary “clearance zone” for holding peace talks. The municipalities were Vistahermosa, La Macarena, Uribe, and Mesetas in Meta department and San Vicente del Caguán in Caquetá department.

The guerrillas‘ clearance plan required that the “Cazadores” Infantry Battalion vacate their headquarters in San Vicente del Caguán, Caquetá. The government, however, insisted that the 130 troops stationed there be allowed to remain.

Eventually, the government and the FARC agreed to demilitarize the five municipalities, except for the Cazadores Battalion. In November, the first 90-day demilitarization period officially began in the five municipalities where talks were to occur. Except for those stationed in the Cazadores Battalion, all soldiers and some police in the newly demilitarized zone were recalled.

(Colombia has several types of police. Those recalled, sometimes referred to as “housed” or “domiciled” police, live in barracks, usually in a compound, as opposed to ordinary street cops that live at home.)

The FARC conditioned the start of official talks on the removal of the Cazadores Battalion and added a new condition. They wanted the government to agree to a controversial prisoner exchange.

Finally, on December 14, FARC leader “Tirofijo” and Ricardo agreed to hold talks on January 7, 1999. Ricardo agreed to withdraw the Cazadores Battalion, apparently without consulting the Colombian Army (COLAR).

Peace talks begin

On January 7, 1999, formal peace talks began between the government and FARC.

Things got off to a rough start when Victor Julio Suarez Rojas, aka “Jorge Briceño Suarez” or “Mono Jojoy“, the number two man in the FARC, threatened to begin kidnapping congress people and other politicians if the government refused to agree to the proposed prisoner exchange.

Pastrana responded that the peace process would end immediately if the FARC carried out Briceño’s threat. By the end of the week, citing an upsurge in paramilitary activity, the FARC “froze” the peace dialogue until April 20. Talks would not continue, a guerrilla communiqué stated, until the government acted against right-wing paramilitary groups (paracas) and military officials believed linked to them.

Though talks with the FARC remained frozen, on February 6 the Pastrana government announced a 90-day extension of the demilitarized zone in southern Colombia. The “clearance” was then set to expire on May 7.

With FARC talks frozen the “hot” war resumed. Three U.S. indigenous-rights activists, Terence Freitas, Lahe’ena’e Gay, and Ingrid Washinawatok, were abducted on February 25 by FARC guerrillas in the northeastern state of Arauca. Their bodies were found on March 6. The three had been working with the U’wa, an indigenous ethnic group in the region. After conducting its own investigation, the FARC admitted responsibility for the murders, asking forgiveness and blaming the act on a low-ranking field commander in the area.

The Colombian government, however, alleged that higher-ranking FARC commanders ordered the killings, including the chief of one group operating in the area, German Briceño (“Grannobles“), the brother of Mono Jojoy.

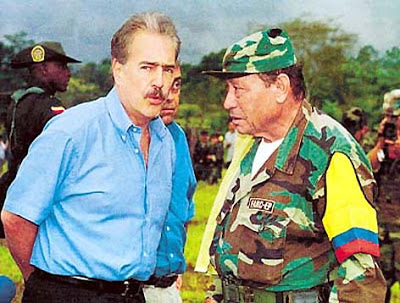

In early May, President Pastrana visited FARC rebels in the “clearance zone” for the second time since becoming president. Pastrana met with FARC leader Marulanda for six hours, convincing him to agree to formal peace talks with the government starting May 6. In a statement, Pastrana mentioned the “unwavering political commitment of both sides to find a political solution to the conflict.”

Although the size of the clearance zone was not expanded, its expiration date was postponed. The two leaders also agreed to form an international commission to verify agreements and monitor FARC actions in the clearance zone.

FARC and government officials met again on May 6 and agreed on a joint Twelve-point Agenda for formal negotiations, a stage that past talks with the FARC were unable to reach. The formal talks were to begin in approximately three weeks.

Just as talks were about to begin, the respected Minister of Defense, Rodrigo Lloreda, threw a hissy-fit and abruptly resigned, citing disagreements over the peace process with the FARC. Lloreda protested statements made on May 21 by government Peace Commissioner Ricardo that the “clearance zone” might be extended indefinitely. The defense minister also cited Pastrana’s failure to return a phone call asking about Ricardo’s statements.

Lloreda’s resignation was accompanied by the alarming resignations of at least 50 other high-ranking officers, including 18 generals. While President Pastrana accepted Lloreda’s resignation, he refused to accept the others. The head of the armed forces, Gen. Fernando Tapias, offered Pastrana a public show of support.

Luis Fernando Ramirez was named as the new Defense minister.

In June, the government announced that the formal negotiations with the FARC would begin on July 7. But on July 6, the government and FARC postponed peace talks until July 19. Reasons given for the postponement were (1) the inability of three members of the FARC negotiating team to arrive at the clearance zone on time, and (2) the need for more time to define “the rules of the game” for the international commission, agreed upon by Pastrana and Marulanda, that would verify conditions in the clearance zone. Things seemed to be back on track, until…

Two days later, the FARC launched a five-day offensive throughout Colombia which one army official called “the largest and most insane guerrilla offensive in the past 40 years.” The attacks occurred in 15 towns, one only 35 miles south of the capital, Bogotá. The guerrillas bombed banks and blew up bridges and energy infrastructure; they blocked roads and assaulted police barracks.

The Colombian military successfully countered the offensive, thanks in part to U.S. intelligence that enabled government aircraft to bomb FARC transports en route to target areas. Government reports claimed that over 300 combatants lost their lives in the fighting, over 200 of them FARC guerrillas. The FARC said the government exaggerated FARC losses.

The Associated Press called a FARC attack on the town of Nariño, Antioquia, “one of the most deadly guerrilla assaults on civilians in memory,” with 300 guerrillas going up against a police station guarded by 35 police officers. The guerrillas‘ use of inaccurately launched bombs made from gas canisters destroyed the downtown area and killed 17 people, including eight civilians, four of them children.

On October 24, between six and 12 million Colombians mobilized in the streets to demand an end to the fighting. Several peace and human rights groups, among them País Libre, Redepaz and Viva la Ciudadanía, organized this nationwide protest against kidnappings and the armed conflict.

This same date also saw a restart of talks between the FARC and the government.

In November, a FARC offensive — believed to be in response to President Pastrana’s call for a holiday cease-fire — dealt the peace process another setback. Colombian armed forces turned back a FARC attempt to take Puerto Inírida, the capital of remote Guainía department.

FARC leaders and Colombian government officials held a televised meeting at Los Pozos, Meta, on December 5, asking the Colombian people for suggestions or questions via e-mail, fax and phone. The event, however, was plagued by technical difficulties which prevented many Colombians from viewing it or contacting participants.

Beginning on December 9 and lasting until December 20, the FARC carried out another offensive, with combat in seven different departments. The greatest casualties resulted from an attack on a naval post in Juradó, Chocó, near the border with Panama, and from a military air attack on FARC fighters outside Hobo, Huila.

On December 20, the FARC announced a holiday cease-fire, calling off military operations until January 10, 2000. Peace talks were to resume on January 13.

On January 14, 2000, FARC leader Marulanda paid a surprise visit to the site of the talks in Los Pozos. Marulanda voiced optimism, stating that talks were near the point at which substantive negotiations, following the Twelve-point Agenda agreed to in May, could begin.

In spite of the imminent peace talks, its Christmas truce over, the FARC carried out attacks again in Nariño department and southeast of Bogotá on the day of the announcement.

With Colombia’s economic model the first topic on the agenda, Finance Minister Juan Camilo Restrepo traveled to Los Pozos in February to meet Marulanda and seven other FARC leaders. He stayed two weeks. The purpose of the meeting was to evaluate the cost of making peace and other economic issues, particularly unemployment

International efforts

At the same time, Peace Commissioner Ricardo and a delegation of FARC negotiators traveled to Sweden, Norway, Switzerland, Italy, France, and Spain on a “tour” facilitated by Jan Egeland, the special representative for Colombia for UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan.

The trip’s primary purpose was to inform the negotiations’ discussion of Colombia’s economic model by familiarizing participants with the mixed economies of Scandinavia and Western Europe. An unstated secondary goal was to increase the FARC’s exposure to a changing world and international expectations.

In March 2000, America Online co-founder James Kimsey traveled to the FARC demilitarized zone for a meeting with Marulanda. The meeting’s purpose was to educate the guerrillas about the changes in the world economy wrought by new technologies and international investment.

A group including some of Colombia’s most important businessmen (known colloquially as “los cacaos“) traveled to the zone to meet Marulanda and the FARC leadership.

Even as the peace process showed progress, the war went on. The FARC earned widespread condemnation by carrying out a brutal attack in Vigía del Fuerte, Chocó, killing 21 policemen and several civilians.

In April, the FARC and Colombian government hosted a “public audience” in Los Pozos, inviting Colombian organizations and citizens to the demilitarized zone for an open discussion on “the generation of employment.” Though the meetings were marked by tensions between representatives of unions and business groups, both called on the FARC to implement a cease-fire, a halt to kidnappings, and respect for international humanitarian law in the conflict.

Government and FARC negotiators announced that a possible open-ended cease-fire agreement was “on the table.” Cease-fire discussions would take place behind closed doors, with confidential proposals. According to reports, the FARC’s proposal foresaw a temporary cessation of hostilities for a fixed period that could then be extended. A bilateral government-FARC commission would verify the agreement. The most difficult condition in the FARC proposal was a demand that the cease-fire apply to all parties to the conflict, including right-wing paramilitary groups.

Mono Jojoy then announced that any person whose net worth exceeded $1 million would be “taxed” by the FARC.

Peace Commissioner Ricardo, in apparent response, announced his resignation. While Ricardo said he was leaving because the peace process had reached “a point of no return,” there was speculation that frequent death threats influenced his decision.

Camilo Gómez, the president’s private secretary and a member of the government negotiating team, replaced Ricardo as high commissioner.

On May 17, 2000, President Pastrana suspended peace talks with the FARC for several days after a woman in Boyacá department was killed by a bomb placed around her neck. It was the first time since the peace process began that the government had suspended the talks. A few days later, the Colombian government acknowledged that evidence did not implicate the FARC in this crime and peace talks resumed.

June came and went with little movement on either side. More than 20 diplomats from Europe, Canada, Japan, and the United Nations meet in San Vicente del Caguán with Colombian officials and FARC leaders to talk about alternatives to drug production. This was the first discussion of drug policy since peace talks began.

On July 3, FARC and government negotiators exchanged cease-fire proposals in sealed envelopes. Though the proposals were to be discussed after a one-month analysis period, no progress was made.

September saw more war than peace. A FARC guerrilla named Arnubio Ramos hijacked a commuter airplane and forced it to land in San Vicente del Caguán, in the FARC demilitarized zone. Government officials insisted that the guerrillas turn Ramos over to show their commitment to the peace process. The guerrillas refused to hand him over, arguing that Ramos hijacked the plane on his own account and “the FARC bears no responsibility.”

The FARC called an “armed strike” in the southern department of Putumayo, where the U.S.-funded anti-drug offensive is very active. Demanding an end to Plan Colombia‘s military component, the guerrillas prohibited all vehicular traffic in Putumayo. As a result, isolated towns and hamlets suffered severe shortages of food, gasoline, and drinking water. The prohibition lasted until early December, when the FARC unilaterally lifted it.

October brought more peace initiatives and voting. More than 300 people met in Costa Rica for a three-day gathering known as “Paz Colombia.” The meeting was designed to increase civil-society participation in peace efforts and to come to agreement on alternatives to “Plan Colombia.”

The meeting brought together representatives from the Colombian government and civil society. More than six weeks after the Arnubio Ramos hijacking, government and rebel representatives resumed talks. Discussions of a possible cease-fire led the agenda.

Four FARC units then launched attacks in Dabeiba, Antioquia, and Bagadó, Chocó. The upsurge in fighting came right before nationwide elections for both municipal and departmental posts. Officials said that, aside from isolated fighting between members of the FARC and army troops in the outlying provinces, the election was carried out with no major disruptions.

On October 15, the FARC declared a unilateral “freeze” on the peace process. The guerrillas said they were suspending talks until the government took firmer measures against paramilitary groups. On October 29, Carlos Julio Rosas, mayor of Orito, Putumayo, was assassinated; the seventeenth Colombian mayor killed that year.

At the end of 2000, Camilo Gomez met with Manuel Marulanda, though the talks remained officially “frozen.” President Pastrana announced that the guerrillas‘ despeje (demilitarized) zone was extended until January 31, 2001.

COLAR chief Gen. Jorge Mora declared that the Army was prepared to reclaim the demilitarized zone whenever it was called upon to do so.

On the eve of the New Year, Diego Turbay, a Colombian legislator who headed a congressional peace committee, was assassinated along with his mother and five other people on a highway in southern Caquetá, not far from the demilitarized zone. The assassination was widely attributed to the FARC, casting further doubt on the future of peace talks.

Year three

The two-year anniversary of the FARC peace talks passed in a moment of pessimism, with dialogue frozen since mid-November. Reports indicated that the FARC might release 100-150 soldiers and police officers in its custody by the middle of February.

On January 23, the FARC rejected a Colombian government proposal for re-starting the talks, which had called for an end to kidnappings and the guerrillas’ use of homemade bombs. With a January 31 deadline for renewal of the demilitarized zone approaching, the COLAR announced that 600 counter-guerrilla troops had been airlifted to sites near the zone. “If Manuel Marulanda wants an extension of the safe haven, he has to sit at the negotiating table,” President Pastrana said.

On the eve of the deadline, Pastrana extended the zone for four more days, asking for a face-to-face meeting with FARC leader Marulanda. Marulanda agreed to meet on February 8-9.

President Pastrana stayed overnight in the FARC demilitarized zone between the two days of meetings with Marulanda. The two emerged with a deal to revive peace talks, the 13-point “Pact of Los Pozos.” Pastrana and Marulanda agreed to extend the demilitarized zone for another eight months, and to negotiate a prisoner exchange and a possible ceasefire.

The Pact created a 3-panel advisory group to report on the paramilitary and guerrilla terrorism problem, side issues that could threaten the peace process, and conditions in the demilitarized zone. The pact, while often ambiguous, increased optimism about the peace talks’ future.

Under a June 2 accord, the FARC agreed to free 42 sick military and police personnel in exchange for 15 ailing guerrillas in government prisons. On June 5, FARC released police Col. Alvaro León Acosta and three other officers, a beginning of compliance with the exchange agreement.

But on June 23, FARC militias attack La Picota prison in southern Bogotá, freeing 98 prisoners, including several FARC members.

Later that week, the FARC unilaterally released 242 soldiers and police agents it had held prisoner, in most cases for years. The group threatened more kidnappings, however. Jorge Briceño told prisoners he released, “We have to grab people from the Senate, from Congress, judges and ministers, from all the three branches (of the Colombian state), and we’ll see how they squeal.”

The public-relations impact of the prisoner release was further dulled by the group’s kidnapping of Hernán Mejia Campuzano, vice-president of the Colombian Soccer Federation. Mejia was not kidnapped because of his position; in fact, the guerrillas released him unharmed on June 29 so that the Copa America tournament, scheduled to begin in mid-July in Colombia, wouldn’t move elsewhere.

Queen Noor of Jordan and America Online founder Kimsey visited the demilitarized zone for a meeting with Marulanda and Gómez in July, but two more FARC kidnappings angered the international community and slowed the peace talks.

On July 15, FARC guerrillas in Meta kidnapped the department’s former governor, Alan Jara, while he was traveling in a clearly marked United Nations vehicle. A FARC statement later accused Jara of paramilitary ties, criticized the UN for transporting him, and promised to submit the former governor to a “popular tribunal.”

Then, on July 16, the FARC kidnapped three German development workers in Cauca department, demanding an end to U.S.-driven aerial spraying of coca plants in the zone (which had started the day before). The UN and European Union issued strong protests.

The Pastrana government named a new team of negotiators (now called “consultants”) for the peace talks: Manuel Salazar, the president’s advisor for social policy; Ricardo Correa, secretary-general of the National Association of Industries (ANDI, one of Colombia’s main business associations); Reinaldo Botero, coordinator of the government’s human rights program; and Luis Fernando Criales, assistant high commissioner for peace for the FARC peace talks.

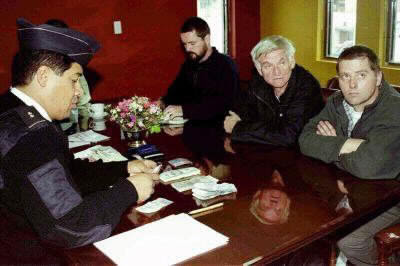

In August, the Colombian government arrested three suspected members of the Irish Republican Army in the Bogotá airport. James Monaghan, Martin McCauley, and David Bracken were accused of spending five weeks in the FARC demilitarized zone, offering training in urban terror tactics.

Finally, in September, a “notables commission” created on May 11 to find solutions to the paramilitary problem issued a report recommending that government-FARC talks proceed under a six-month cease-fire. Under this proposal, the FARC would abstain from kidnappings and extortion, while the government would pay for the FARC members’ basic needs and refrain from herbicidal spraying of small-holding coca-growers.

On September 29, Liberal Party presidential candidate Horacio Serpa was forced to give up an attempt to lead a protest march into the FARC demilitarized zone. FARC fighters at the zone’s entrance fired warning shots with rifles and mortars, calling into question the status of the zone just over a week before its renewal deadline.

Soldiers then found the body of Consuelo Araújonoguera, a popular former minister of Culture and the wife of Attorney-General Edgardo Maya. Araujonoguera had been kidnapped September 24 by the FARC at a roadblock near Valledupar, Cesar. The FARC admitted the kidnapping but denied the murder, though witnesses say Araujonoguera’s guerrilla captors shot her at pointblank range while being pursued by COLAR.

Days before the FARC demilitarized zone’s next expiration deadline of October 10, FARC and Colombian government negotiators signed the “San Francisco de la Sombra Accord,” renewing the zone until January 20, 2002. (FARC negotiators expressed disappointment that it was not renewed until August, when President Pastrana’s term would end.)

The accord committed both sides to focusing talks on conditions for a cease-fire, and the FARC pledged to cease its practice of “miracle fishing,” staging roadblocks and kidnapping travelers for ransom. The government pledged to increase anti-paramilitary efforts.

In a letter to his negotiators, dated November 7, Marulanda listed demands for the stalled peace talks’ resumption. These included, among other items, suspension of government over-flights of the demilitarized zone, a government affirmation that the FARC are not terrorists or narco-traffickers, an end to military incursions in the zone (COLAR denied any such episodes had occurred), and suspension of the government’s ban on unauthorized foreigners in the zone.

If these demands were not met, Marulanda said, “it will be necessary to agree upon a day… to officially hand over” the demilitarized zone to the government. President Pastrana and other government officials rejected Marulanda’s “ultimatum.”

Residents of the indigenous community of Caldono, Cauca, resisted an attempted FARC takeover of their town by assembling nonviolently in the town center. Similar examples of nonviolent resistance to incursions followed in several indigenous towns in southwest Colombia. FARC fighters killed some nonviolent resisters in Purace, Cauca, on December 31, 2001.

FARC leader Marulanda invited Pastrana, leaders of business groups, Colombia’s Congress, judiciary, and the Catholic Church to a January 15 meeting in the demilitarized zone. The meeting, Marulanda indicated, would seek to determine “what is negotiable” among a list of concerns, among them Plan Colombia, drug crop eradication, prisoner exchanges, and paramilitarism. The meeting would occur five days before the January 20, 2002, deadline for expiration of the demilitarized zone where talks were taking place. The Colombian government declared it would “study” Marulanda’s proposal and respond in writing.

Year four

The third anniversary of the beginning of peace talks rolled by. The FARC and Colombian government agreed to hold talks, for the first time since mid-October, on January 3 and 4, 2002. According to a January 3 FARC communiqué, the talks’ purpose was “to find formulas to get the process moving and to allow for discussion” of the talks’ common agenda, a cease-fire, subsidies for the unemployed, the September recommendations of the “notables commission,” and the previous October’s San Francisco de la Sombra accord.

No progress was made in two days of talks. The FARC continued to insist that the government lift the control measures it had implemented in the area surrounding the group’s demilitarized zone, such as border controls and air patrols that the guerrillas viewed as tantamount to a blockade. Arguing that the control measures had brought a reduction in kidnappings, the government, particularly armed forces Chief Gen. Fernando Tapias, made clear its intention to keep them in place.

On January 8, another meeting between the FARC and the government failed to make progress. The FARC continued to cite government controls on the demilitarized zone as the chief obstacle to progress and to the guerrillas‘ compliance with the San Francisco de la Sombra accord. In a letter, Marulanda left the talks’ future up to Pastrana. He also proposed a timetable, should the present difficulties be overcome: discussion of a subsidy for the unemployed in February and March, and discussion of a ceasefire in April and May. The FARC released a series of open letters to officials and sectors of society.

The next day, the Colombian government announced the suspension of peace talks. The military was to enter the demilitarized zone 48 hours after Pastrana issued an order. The U.S. State Department blamed the FARC for the talks’ collapse.

As troops massed on the fringes of the demilitarized zone, Pastrana granted the United Nations time to find a solution to the stalled dialogues with the FARC. If no agreement was reached, the 48-hour countdown for the guerrillas’ exit from the zone would begin the evening of Saturday, January 12.

UN representative James LeMoyne arrived in the demilitarized zone in early afternoon of January 11 for last-ditch talks with the FARC. The two sides had until 9:30 pm the following day to find a way to save the peace process.

After two days of talks with LeMoyne, the FARC released a proposal for re-starting the peace talks, just before the 9:30 deadline. The guerrillas’ draft re-affirmed the commitments of the San Francisco de la Sombra accord, but left out the question of government controls in the area surrounding the demilitarized zone. The FARC had demanded that these measures be lifted in order for talks to continue.

To most observers, the statement tacitly acknowledged that the FARC had yielded on the issue of the control measures, though the guerrilla proposal would create a commission to investigate complaints about the measures.

At midnight, Pastrana rejected the guerrillas‘ proposal and ordered COLAR to re-take the zone at 9:30 pm on Monday, January 14. Pastrana offered one last hope: that the guerrillas clearly state that the dialogues may continue even with the control measures in place. The UN’s Lemoyne and FARC negotiators continued meeting on January 13.

The FARC announced that they would hand over the demilitarized zone’s town centers, officially ending the three-year-old peace process.

In late afternoon on the 14th, after a day of efforts from the UN, international, and church representatives, the FARC announced that guarantees existed for the peace process to continue, complying with President Pastrana’s demand. The January 20 deadline for the demilitarized zone’s renewal remained in place, Pastrana said, unless both sides could agree on a strict timetable for cease-fire discussions. Future talks would include international representatives in a more formal fashion.

FARC offensives on February 5, much of it sabotage of infrastructure and bombings of urban areas, further increased skepticism about the peace process. The Colombian government issued a proposal for a six-month cease fire.

Shortly before the February 14 deadline for expiration of the guerrilla demilitarized zone, the FARC and the Colombian government agreed to a timetable for cease-fire discussions. The main issues to be discussed were cease-fire terms, kidnapping, and paramilitarism. The document, drawn up in the presence of UN, foreign embassy, and church representatives, laid out a brisk schedule that would bring a cease-fire by April 7. President Pastrana extended the demilitarized zone until April 10.

As time ran out on the FARC peace process, several presidential candidates, including Horacio Serpa, Luis Eduardo Garzón, and Ingrid Betancourt traveled to the demilitarized zone for a meeting scheduled as part of the peace talks’ timetable. All candidates sharply criticized the guerrillas’ ongoing offensive against civilian targets.

FARC and government representatives exchanged cease-fire proposals. The government proposal called for maintaining guerilla fronts in small zones to keep them separate from the armed forces.

February 20, 2002. Last call.

The end of the FARC peace process

The FARC hijacked a domestic airliner, forcing it to land on a stretch of highway in Huila department. All passengers were freed but one, Colombian Senator Jorge Gechem Turbay, the fifth member of Colombia’s Congress to be kidnapped by the guerrillas since June 2001.

President Pastrana responded by announcing the end of the three-year-old talks with the FARC. Aerial bombardment, the first phase of military operations to re-take the demilitarized zone, began at midnight.

It should be noted that this declaration was signed in Washington, D.C., where Pastrana had gone to receive orders from his masters of war.

Senator and presidential candidate Ingrid Betancourt was kidnapped three days later by FARC while traveling to the former demilitarized zone on a mission to advocate respect for the rights of the zone’s residents.

The FARC gave the Colombian government one year to negotiate the exchange of Betancourt and five other kidnapped legislators for FARC prisoners in Colombian jails. She was freed by the COLAR six and a half years later.

Presidential elections were held on May 20, 2002. Alvaró Uribe Velez won. That was the end of the “peace process” as it relates to the FARC.

Under the Uribe regime, a new and different kind of “peace process” would take place.

Next: Colombian peace process, Part two: the AUC. (This very different peace process, between the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia [AUC], [United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia] and the government of Alvaro Uribe Velez, began even as the previous one with the FARC failed.)

geez, Delgado, so are there any Good Guys down there? How are we Americans spozed to understand a conflict in which no White Hats have been distributed??

Where did you get your information? Who/what are your sources?