Colombia’s Uribe:

Playing politics with Pablo

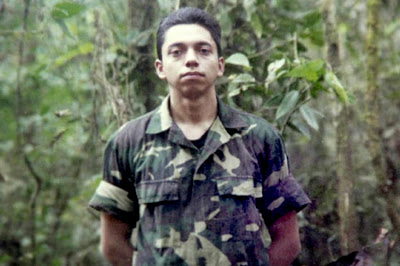

Somewhere in the Amazon jungle tonight, Pablo sleeps chained to a tree stump, his release prevented by the government he served all these long years in order to continue the class warfare that U.S. taxpayers pay for.

By Marion Delgado / The Rag Blog / January 6, 2010

CARTAGENA DE INDIES, Colombia — On 21 December 2009, Pablo Emilio Moncayo marked his 12th year as a captive of Colombia’s Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia — Ejército del Pueblo (FARC or FARC-EP; Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – Peoples Army).

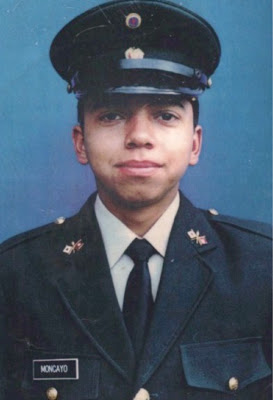

While President Uribe’s propaganda machine says that he was kidnapped, he was actually captured in battle in 1997. Pablo was a corporal in the Colombian Army (COLAR) then; he has been promoted to sergeant while a POW. Like all stories, Pablo’s began many years before he became a pawn in the decades old military/political class struggle between COLAR and FARC-EP.

Like many revolutionary armies, FARC-EP began as a rag-tag group of campesinos protecting an agrarian class displaced from their land by rich landowners. That was in the late 1950s. Because of the brutal opposition it met, the FARC had to become not just a defensive, protective force for the people, but an army with offensive capabilities. They declared themselves a belligerent army in 1964 and named themselves the FARC in 1966.

Pablo Moncayo was four years old in 1982, when the events that led to his current situation began to take shape.

At the Seventh Guerrilla Conference in 1982, work began to turn the FARC from a guerrilla organization into a rebel army (the “People’s Army”). FARC added ranks and badges to its uniforms, introduced a new inventory system for firearms and ammunition, and provided new weapons and technology for FARC militants.

In theory, a properly organized and trained guerrilla army would thus meet the international requirements for recognition of a “state of belligerence” as defined by the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and later protocols. FARC considers that it lives up to this definition and argues that it has been accepted as a legitimate army, in particular during negotiations with successive Colombian governments.

FARC opponents and the government claim that the group’s practices of civilian kidnapping for ransom and taxing coca crop buyers make it an illegitimate army and point to a wide rejection of FARC positions in national surveys. Assassinations of opponents and forced displacements are inflicted on the general population by all forces involved in the Colombian civil war, making FARC’s belligerent status claim harder to accept. This is further complicated by the coca eradication efforts of the Colombian government that involve U.S. support and that have led to FARC being declared a terrorist organization by the U.S. government and the EU.

FARC maintains that it does not grow or process or transport Colombia’s main agricultural crop, cocaine. It admits that it taxes those who do. It taxes all commerce in the territory ceded to it by the former Pastrana government in a peace agreement, territory that the Uribe government is now trying to retake by force of arms.

Aware of these roadblocks to legitimacy, FARC one year ago released the last of its civilian hostages. Those captured in battle, however, are still held.

On December 21, 1997, COLAR was building a communications station in Patascoy, in the state of Nariño, close to the border of Putumayo, when the construction unit was attacked by the FARC. Twenty-two COLAR soldiers were killed and 19 were captured, among them Corporal Moncayo, almost as low as you can get on the military totem pole. FARC causalities were not reported.

In 2007, Pablo’s father, Gustavo Guillermo Moncayo Rincon, a teacher popularly known as “El caminante por la paz” (“the walker for peace”), walked 1,186 km from his hometown, Sandoná, in the department of Nariño, to the capital, Bogotá, seeking an agreement for the release of his son, who had by then been a prisoner of the guerrilla group for 10 years.

On June 17, 2007, Father’s Day in Colombia, Moncayo began walking from Sandoná accompanied by his daughter, along the Pan-American Highway, stopping in every town along the way to rest and to collect signatures for a petition to President Álvaro Uribe, asking him to conduct a prisoner exchange.

When he arrived in Cali, he was received by Governor Angelino Garzon, who offered him a place to stay. Days after, in Pereira, he was received by the mayor, who decorated him as a “citizen of honour.” He walked across the highest pass of the Andes, and on August 1, 2007, Moncayo walked the last stretch to the historic downtown of the capital city. When he arrived in the Plaza de Bolívar he was cheered by thousands of people. His arrival led to a public exchange of views in the press between him and Uribe, who blamed Pablo Moncayo’s long captivity on the FARC.

After this fruitless exchange, Moncayo said, “Sadly, our children, our loved ones, remain there in the jungle… We are in the middle of this political game between the government and the FARC.” He also criticized Uribe for “making empty offers to the guerrillas in exchange for the captives.”

According to the Washington Post, Fernando Londoño, a far-right former interior minister, criticized Moncayo in an opinion column for El Tiempo, the country’s main daily. (El Tiempo is owned and operated by the family of Colombia’s recent Minister of Defense, Juan Santos, and is a frequent source of government propaganda.) He accused Pablo Moncayo of being an “incompetent soldier,” and wrote that his father was spreading “Marxist venom through Colombia’s veins.”

Gustavo Moncayo continued to work for his son’s release, collecting petitions, visiting politicians, and talking with anyone who would listen. Early in 2009 his work seemed to pay off. An international outcry began to take hold and in April, responding to a call from Hugo Chavez, the president of neighboring Venezuela; President Rafael Correa of Ecuador; Senator Piedad Córdoba, known as the “peace senator”; Amnesty International; the Catholic church; and the International Red Cross, the FARC announced they would “unilaterally” free the soldier they had held hostage for over 11 years as they look for ways to start peace talks with the government.

It looked like Pablo was coming home. Senator Córdoba and the Red Cross were named as intermediaries. Still Uribe was reluctant and dragged his feet over arrangements, all the while keeping up a steady stream of vile and unhelpful statements.

The FARC said it would unilaterally free Pablo Moncayo and turn him over to his father and the left-wing Córdoba, who has brokered hostage handovers in the past, and that it wanted the release to begin the start of peace talks with the government. Uribe responded by insisting that the rebels “first must cease bombing, kidnapping, and drug smuggling.” At every turn he seemed to be trying to derail Pablo’s release.

On December 22, 2009, he saw his chance to nix the deal once and for all. That was the day 10 heavily armed men in civilian clothes kidnapped and murdered the governor of the state of Caquetá, Luis Francisco Cuellar. Without any proof at all, Uribe immediately announced that the perpetrators were the FARC.

In his usual hate-filled rhetorical style the president announced that the assassination of Cuellar gives him great “pain” and “desperation.” Uribe said the crime was the work of the “same bandits who want to make the release of the hostages a show.” The president was referring to a statement that FARC made several months ago about their readiness to free two soldiers (including Pablo Moncayo), and return the remains of a policeman who died in captivity.

Uribe stated that he has done everything required by the FARC and therefore no longer believes in the promises of “these bandits,” insisting that the military will rescue the hostages.

But Uribe has not done anything FARC has asked. He refuses to take this release as an opening for peace talks. He would not even sign an agreement guaranteeing the safety of the people involved in the release, including the senator and Red Cross representatives.

In 2002, when peace talks were initiated; Uribe loosed paramilitary thugs who used the occasion to kill some FARC negotiators. He put an end to that peace process and insured more years of “dirty war” and billions of U.S. taxpayer dollars to fill his and his cronies’ coffers.

The FARC website had this to say:

“Because Uribe and his gang did not sign the decree which guarantees security for guerrillas and guests, you can not believe anything. The only thing stopping this humanitarian act has its own name: Uribe Velez.” The website added, “The FARC knows that the Colombian oligarchy and its transitional form, Uribe, are tráfugas and not ‘a tantico to be trusted’.”

According to information obtained by ANNCOL, the FARC remains ready to fulfill its word, freeing the two soldiers and returning the remains of the policeman.

Meanwhile, Pablo Emilio Moncayo’s father, Gustavo Moncayo, charged that Uribe’s statements “continue to insist on preventing” the release of his son and asked him not to endanger the lives of the hostages with a military type rescue.

Uribe was not to be deterred by the father’s pleading. “The instruction is to rescue,” Uribe said. “I have asked all military and police efforts to rescue the other hostages that were retained from these bandits.”

Uribe got what he wanted. On December 24, the Red Cross announced it had suspended negotiations to release the hostages. A representative of the organization in Colombia (ICRC), Pascal Jequier, told the BBC that the decision was made after President Uribe ordered a military rescue of the governor of Caquetá, Luis Francisco Cuellar, and other hostages. Uribe issued the “rescue” order before Cuellar’s death was known, placing other POWs in danger.

“As long as the order is in force to act through military means to rescue the hostages, there will be no release sponsored by the ICRC,” Jequier said, adding that,”Efforts to seek the release of Corporal Pablo Emilio Moncayo and the soldier Joshua Daniel Calvo remain ‘frozen’ at the moment.”

Somewhere in the Amazon jungle tonight, Pablo sleeps chained to a tree stump, his release prevented by the government he served all these long years in order to continue the class warfare that U.S. taxpayers pay for.

“He’s only a pawn in their game.” — Bob Dylan

With so much kidnapping going on, and the big build-up of US troops and bases in Colombia, how long will it be b4 some kid from Generica is chained to that same tree with Pablo? The father’s efforts — incredible! What will US parents do when it’s their kids who disappear for TWELVE YEARS???

right on, Delgado!!!

It is the government’s fault because the rebels have held one of their soldiers captive for twelve years. Right.

All the government has to do is cave in to the rebel demands and they will release him.

How about this: the rebels agree to lay down their arms and the government promises to grant them amnesty—-after the arms are turned in.

This article is BS. They’ve held the guy hostage for twelve years. Turn him lose and show what a bunch of fine humanitarians they are. He is of no use to them as a captive.

Anon,

The government of Colombia should “cave in” to the People’s Army demands in this case. The demand is that Uribe guarantee the safety of those involved in the hand off of Sgt. Montoya, the IRC personal, the peace Senator, and Montoya himself. In fact just the opposite has been promised, that the Colombian Army will “rescue” Montoya by fuego, and offers no protection to the humanitarian workers. A simple guarantee of 24 hours would have had the Sgt. home two years ago.

md