A Promise of Peace:

Colombia and the paramilitary warlords

By Marion Delgado / The Rag Blog / March 3, 2010

Part two: The AUC

CARTAGENA DE INDIES, Colombia — In my last posting, I examined the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia — Ejército del Pueblo, (FARC or FARC-EP; Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia — Peoples Army)/former Pastrana government’s three year attempt to find a road to peace in Colombia (1999-2002). Due to intransigence on both sides, no road was found and the peace process as far as the FARC was concerned ended on February 20, 2002.

On that day another “peace process” was already secretly in the works; this one very different from the FARC experience. The new process, between the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC, United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia) and the government of Alvaro Uribe Velez, began even as the previous one with the FARC failed.

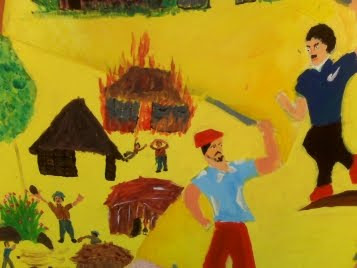

AUC was created as an umbrella organization of regional far-right paramilitary groups, each intended to protect different local economic, social, and political interests by fighting insurgents in their areas. The hallmark of right-wingers, no matter where they appear, is that they consider themselves patriots, and their deeds to be in the service of their country, however dastardly or illegal. Such was the position of the AUC.

Carlos Castaño was one such “patriot.” He was 16 years old when, in 1982, he and his older brother Fidel joined an army-sponsored “self-defense” group, Muerte a Secuestradores, (MAS, Death to Kidnappers). He received his military training from the Bombona Battalion of the Colombian Army (COLAR)’s 14th Brigade. (See my Rag Blog article on “false positives” about licensed murder in Colombia, for more about the 14th.)

MAS provided the model for many regional “self-defense” groups that proliferated around the country in the ’80s and ’90s, and that were transformed into a united national force, under Castaño’s command, in l997: AUC.

Carlos has been quoted as saying Uribe was the presidential candidate of AUC’s social support base. “Deep down, he’s the closest man to our philosophy,” Castaño said, adding that it was Uribe’s support, when a senator, for the right to self-defense from “guerrillas” that gave rise to paramilitarism in Colombia.

After 2000, the direction of the AUC began to change. Its leadership splintered, and the group reconstructed itself in an effort to eliminate, or at least control, smaller factions more involved in narco-trafficking than in ideology.

Fabio Ochoa Vasco, an extradited drug trafficking paramilitary member, testified that he witnessed a conversation between AUC’s leaders and supposed representatives of Uribe’s campaign before Uribe’s first Presidential election. “They talked about the peace process; they said anyone with problems with the U.S. could get involved. In another meeting, there were businessmen, landowners, and drug traffickers who [the AUC] thought could also be included, so they told them to get ready for the peace process.”

The demobilization process

In December 2002, four months after Uribe took office, the AUC accepted a cease-fire and entered into peace negotiations with Colombian authorities.

Since then, many militants have surrendered their weapons in exchange for amnesty from extradition on drug charges to the U.S. Official pardons or other specific solutions were provided, such as reduced prison sentences or meager economic assistance to families of AUC victims (demobilizing militias were supposed to make some “restitution” to victims), in exchange for testimony.

The government promised legal identity documents, a two-year subsidy, and educational and employment opportunities to anyone participating in the process who did not face pending legal charges. This lenient attitude, coupled with short sentences and minimal fines, demonstrated the “sweetheart” elements of the program.

Cacique Nutibara bloc

The first bloc to “demobilize” was the Cacique Nutivara Bloc (BCN), founded by Diego Murillo Bejarano, aka “Don Berna.”

In what many reporters described as a made-for-TV production, 855 fighters of the BCN piled weapons and ammunition on the floor of the Medellin convention center. The government touted the November 25, 2003, disarmament ceremony as a first step toward ending four decades of war. Many national and international human rights organizations, however, saw it as a confirmation that President Alvaro Uribe was, at best, guaranteeing the impunity of paramilitary groups, and at worst merely recycling them.

For example, before the BCN demobilization, the paramilitary force recruited young men for the sole purpose of participating in the demobilization ceremony, enticing them with promises of generous allowances and other benefits. Allegations of fraud were so widespread that then-High Commissioner for Peace in Colombia, Luis Carlos Restrepo, said that “they [BCN] stirred up street criminals 48 hours before [demobilization] and put them in the package of the demobilized.”

Officials from the Permanent Unit for Human Rights of the Medellin Personería (a government bureau) estimated, from surveys conducted in Medellin neighborhoods, that approximately 75% of those demobilized with the BCN were not really fighters. If this is accurate, then for all the hoopla, only 214 paracos were actually demobilized that day in Medellin.

Similarly, in Norte de Santander, in the Catatumbo Bloc demobilization, although most party members joined the process, people who had never belonged to the group also “demobilized,” seeking economic benefit. They approached the bloc’s chief, who said, “If you want to go, you can go.” In other regions, such as Nariño, paramilitary leaders mounted a supposed demobilization, but without key members who continued to exercise territorial control.

In mid-May 2004, the peace talks appeared to move forward as the government agreed to grant the AUC leaders and 400 of their bodyguards a 142 square mile (368 sq. km) safe haven in Santa Fe de Ralito, Córdoba, where, under Organization of American States (OAS) verification, further discussions would be held, for a (renewable) trial period of six months. As long the AUC leaders remained in this area, they would not be subject to arrest warrants or extradition to the U.S., where a few faced indictments for money and drug trafficking.

That condition, and most of the legal framework for the AUC’s safe haven, had been previously implemented for the much larger San Vicente del Caguán safe haven that former President Andrés Pastrana had granted FARC guerrillas during the 1998-2002 peace process, but there were differences:

- the local, and state police authorities would not leave the zone, so Colombian laws would still be fully applicable within its limits

- Paramilitary leaders would require special permission to leave and re-enter the zone, and government prosecutors would be allowed to operate inside it in order to investigate criminal offenses.

Uribe double-cross

Back in Washington, G.W. Bush, himself a torturer and war criminal, thought the process being played out was too lenient to the AUC narco traffickers and, pressed by his right-wing drug warriors, told Uribe that extraditions would be necessary.

Many AUC leaders had already made “confessions” to avoid extradition and receive sweetheart jail terms. They saw this as the double-cross it was.

In November, 2004, the Colombian Supreme Court approved the extradition of top paramilitary leaders Salvatore Mancuso and Carlos Castaño, together with guerrilla commander Simon Trinidad, the only one of the men in state custody. Castano was already dead; in April he’d been ambushed by 20 elite paramilitaries on orders from AUC’s new top leaders. He was shot almost two dozen times in the face, chopped into pieces, and burned.

The court ruled that the extradition requests, all on charges of drug trafficking and money laundering, respected current Colombian law and therefore could proceed, once Uribe gave his approval. He did as his U.S. masters of war told him and signed off on the deal. In the meantime, the “demobilizations” continued.

Bloque Norte (Northern Bloc)

The most obvious case of fraud was with the demobilization of the Bloque Norte, which had a strong presence in the coastal departments of Cesar, Magdalena, Atlantico, and La Guajira.

Between March 8 and 10, 2006, 4,759 suspected members of the Northern Bloc demobilized along with their leader, Rodrigo Tovar Pupo, a.k.a. “Jorge 40.” However, the next day, investigators from the Human Rights Unit of the Attorney General’s Office captured Edgar Ignacio Fierro Florez, also known as “Don Antonio,” a member of the Northern Bloc who had participated in the demobilization ceremonies, but continued directing the group’s operations. In the raid, investigators found computers and a huge number of electronic and print files on the Northern Bloc.

Computer files showed that the demobilization of the Bloque Norte was a massive fraud. According to reports, the files contained emails and conversations that allegedly involved Jorge 40. Those messages directed his lieutenants to recruit, from among the peasants and unemployed, as many people as possible to participate in the demobilization.

The messages included instructions on how to prepare these civilians for the demobilization ceremony, so they would know how to march and sing the anthem of the paramilitaries. Details such as where to get uniforms and instructions to guide the “demobilized” about questions prosecutors would ask, and how they should respond, were included.

For example, messages stress that these people should say that the bloc had no members in urban areas, although it was actually still operating in Barranquilla. One message says that Northern Bloc leaders had given a list of those to be demobilized to the Administrative Security Department (DAS) to determine whether any had criminal records and that DAS had confirmed none did. Other messages discussed which group members should demobilize in order to continue exerting control in key regions.

The Interamerican Human Rights section of the OAS, present at the demobilization of the Bloque Norte, expressed concern about the situation of fraud:

A number of people seeking to demobilize as combatants did not show the features of paracos. We were concerned about the small number of fighters (‘patrol’) compared to the number… claiming to be radio operators (‘radio sparks’), responsible for distributing food, or women responsible for domestic chores (‘washers’)… Repeatedly they said that they obey direct orders from the ‘maximum leader’ of the Bloque Norte, Jorge 40, keeping silent about… the… middle of the… structure, and that subtracted credibility from their statements.

The human rights organization’s fears became a reality when the BCN was implicated in a massacre on January 29, 2005, in San Carlos, Antioquia, in which seven persons, including two children, were killed, some 14 months after that bloc “demobilized.”

The massacre caused a rethinking of the demobilization process and sparked the initiation of the Justice and Peace Law of 2005. With the amendments of the Court, this law requires full and truthful confessions, states that reductions in sentences can be revoked if demobilized paramilitaries lie or violate various requirements, and does not set deadlines for investigations. The Court removed sections that would have allowed paramilitaries to serve their sentences outside prison and to count the time during which they were negotiating with the government as time served.

The vast majority of people who were then “demobilized” did so under this legislation, with special rulings for reductions in penalties for serious crimes. But most were simply seeking economic benefits and pardons for their participation in the group, in accordance with Act 782 of 2002 and Decree 128 of 2003. (See sidebar below.)

Until July 2007 the Colombian government interpreted Act 782 and Decree 128 as allowing it to grant pardons or halt prosecutions for the crime of conspiracy (the charge brought against most paramilitaries) and other related crimes, such as illegal arms possession.

Thus, the thousands of people involved in demobilization ceremonies only had to answer a series of questions from prosecutors; then they got pardons or the halting of criminal proceedings against them. They then joined rehabilitation programs that offered them stipends and other economic and social benefits, without their being subject to any more scrutiny by authorities.

The AUC included several groups not primarily focused on counter-insurgency, such as Don Berna’s outfit in Medellin that focused largely on controlling crime. The same is true of AUC’s Central Bolívar Bloc, led by Carlos Mario Jimenez Naranjo (“Macaco“); the South Libre Bloc, led by Rodrigo Perez Alzate (“Pablo Sevillano“); and the Pacific Bloc, run by Francisco Javier Zuluaga (“Gordolindo“).

After a cease fire was declared (now publicly admitted by the AUC and the government to be partial, resulting in a reduction but not cessation of killings), the Uribe government began talks with the AUC with the aim of eventually dismantling the organization and reintegrating its members into society.

The stated deadline for completing the demobilization process was originally December 2005, but was later extended to February 2006, then again to August 15, 2006, to be sure to include all the murderers. Between 2003 and February 2, 2006, about 17,000 of the AUC’s 20,000 fighters surrendered their weapons. After the last extension, the number climbed to 31,671 according to Human Rights Watch. This is more than triple the number estimated by the government to be involved before negotiations began.

And so ends the saga of a second peace process, and according to the Colombian government, the beginning of the end of AUC and paramilitarism there.

The extraditions, however, continue. In the early morning of May 13, 2008, 13 high-profile paramilitary leaders were taken from their jail cells in a surprise action by the Colombian government. According to Interior Minister Carlos Holguin, they had refused to comply with the Peace and Justice Law and were therefore extradited to the United States. Among them were Salvatore Mancuso, Don Berna, Jorge 40, Cuco Vanoy, and Diego Ruiz Arroyave (cousin of assassinated paramilitary leader Miguel Arroyave).

President Uribe said immediately afterwards that the U.S. had agreed to compensate the victims of the extradited paramilitary warlords with any international assets they might forfeit. The U.S. State Department said the U.S. courts can also help victims by sharing information on atrocities with Colombian authorities.

Can this really be true? Watch for the next posting: “The Resurgence.”

Legal framework of demobilization

Colombia’s Act 418 of 1997, as amended by Act 782 of 2002, stipulates that “the National Government may give the benefit of a pardon to citizens who have been convicted for acts constituting a political offense, when the armed group is outside the law, with which a peace process has gone forward and has demonstrated its willingness to rejoin civilian life.” (Art.50)

The same article stipulates that it is “not to apply the provisions of this title to those engaged in conduct involving atrocious acts of ferocity or barbarism, terrorism, kidnapping, genocide, murder committed outside combat, or placing the victim in a defenseless state.”

In addition, National Decree 128 of 2003, regulating Act 782 regarding the collective demobilization of paramilitaries, states that authorities “have the right to pardon, conditionally suspended execution of sentence, the termination of proceedings, preclusion of the instruction or inhibitory orders, depending on the state of the process, the demobilized who have been part of armed groups outside the law, for which the Operative Committee for the Surrender of Weapons, CODA, issued the certificate… ” (Art. 13)

From 1997 until 2007 the government thus operated on the theory that paraco crimes were political in nature and granted pardons under Act 418. Without these acts, under Act 782, political crimes were the only “unpardonable” crimes in Colombia. However, in July, 2007, the Supreme Court of Colombia ruled that the crimes of the paramilitaries were not “political crimes.”

The Court’s decision, while not specifically referring to Act 782, was contradictory to the government’s interpretation, which said that the paramilitary pardons were political offense pardons.

Instead of seizing this opportunity to restructure the process of demobilization and conduct more serious interviews and investigations of paraco crimes, President Uribe reacted to the ruling by accusing the Court of exercising an “ideological bias,” arguing that the Court’s independence of the was only “relative,” and that “all state institutions must cooperate for the good of the Nation.”

Administration officials said the ruling could derail the demobilization process, as approximately 19,000 people who had participated in demobilization ceremonies had not yet received pardons, and not allowing them this benefit would have a negative impact.

To avoid having to investigate demobilized people, in July 2009 the Colombian Congress amended the Criminal Code so that the Attorney General could use what is known as the “principle of opportunity” to halt investigations, or simply refuse to prosecute.

To achieve genuine and lasting demobilization of paramilitary groups, the government must focus on the sources of the paramilitaries’ power: drug trafficking and the property, persons, and entities that support them among the political and military elites.

However, due to the nominal retribution aspects of the demobilization process — the easy terms, the pitifully small amount of compensation paid to survivors of those murdered by the AUC, and the guarantees that if they confessed they would not be extradited to the U.S. — the integrity of the program was drawn into question.

Though its control over various geographic regions and its share of the narcotics industry appeared to dwindle, in actuality, the AUC still maintained significant control over the economic and political structures of Colombia. For example, AUC members were affiliated with various mayoral, gubernatorial, and council positions in important areas, thus leading to their well-documented claim to influence 30% of the Colombian Congress.

—md

- Also see “Colombia and FARC : Six Long Decades of Fighting for Peace, Part one, Peace and the FARC” by Marion Delgado / The Rag Blog / February 20, 2010