John Clay, whose unique musical vision reflected a vicious honesty tempered only by his darkly innocent sense of humor, is dead at 74.

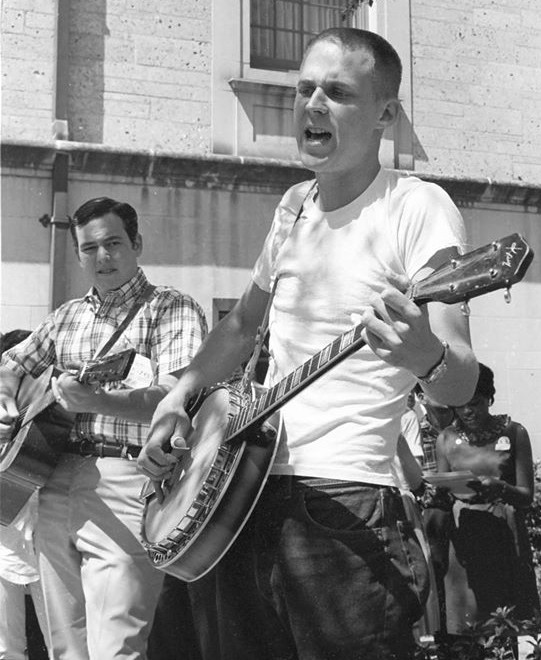

John Clay performs on the UT-Austin campus in 1965 at a rally for Gary Thiher, SDS candidate for student body president. Photo by Jim McCulloch.

AUSTIN — Austin lost its most unique and unforgettable voice when John Clay died Wednesday, December 17, 2014, at the age of 74. Intense, direct and fiercely distinct, with a vicious honesty that was tempered only by his darkly innocent sense of humor, John had an innate ability to capture so much of life in such a very few words even though many of his songs, like “West Texas Memories,” were notorious for length.

Epic numbers like that brought listeners along for a seemingly endless ride through the flatlands of memory that in the end turned out to be over much too soon. Some, like “Mr. Bowly’s Still” or “The Meter Reader” were deliciously compact vignettes, like Thurber with a southern accent, or cummings with capitalization, set to music.

In a world of pretenders, John was an observer. Between the lack of pretense and the brutal nature of his observational skills, it is no wonder that his art remains obscure. But the stark and predictive despair of songs like “No Blade of Grass,” the knife-edge hilarity of “America After Five,” raucous commentary of “Bad Boy, Come Home,” or the sweet and genuine poignancy of “I Remember Florida” open the door to more than a few worlds that have all but disappeared.

“He blew down from Stamford Texas

North of Abilene

A lanky kid with a banjo on his knee.

With a pocket full of songs to sing and a

Personal point of view,

Those Austin folks had never

Heard nor seen.”

— Powell St. John (from the song “John Clay”)

Austin, Texas, back in the 1950s would seem like a really weird place to us now. Conventional, conformist, deeply racist and, in step with the times — intolerant, suspicious and vengeful. By what circumstances we’ll never know, but something special took hold in the backyard bamboo jungles near 29th and Nueces streets, where apartments could be found.

There like-minded youngsters enjoyed newfound freedom, cheap rents, and a place

to start something.

There like-minded youngsters enjoyed newfound freedom, cheap rents, and a place to start something. Surrounded by sheltering trees, the little compound that had come to be known as “The Ghetto” was a welcoming roost where John Clay found himself at last among others of his own kind.

“John Clay lived above the garage if there was one, or else he lived above Ted Klein and his wife and their little peyote-eating dog. There was an outside stairway up to John’s place.”

— Wali Stopher

Born on August 12, 1940, in Evansville, Indiana, John Clay was the younger of two children of John Withers Clay III and Leota Ullman Clay who had been living an idyllic life in Minnesota. John’s older brother, Clement Comer Clay, born in 1925, was to all accounts a model child, growing up straight, strong, and obedient. Destined to excel in life, work, and sport, he was the apple of his mother’s eye. The tragedy of his untimely accidental death by drowning cast a shadow on the young family. It was devastating and had a profound and lasting effect on his mother, all before John himself was born.

Little is recounted of the intervening period, but though Leota wanted another son it was many years before she bore John Withers Clay IV. John was very different from his brother. The matchless presence of Clement’s memory and his mother’s overpowering grief at the loss never really subsided and ultimately did damage to the family. No one knows all the reasons, but early in John’s childhood his parents divorced. His father moved to Florida and John went with his mother to Dallas and eventually, after she was remarried to a prominent cattleman from West Texas, to Stamford where he grew up under difficult circumstances.

John felt the loss of an older brother

he never knew.

Not much is known of those years, but the lyrics to “The Twenties Song” have something to say about the matter. John felt the loss of an older brother he never knew, and suffered other things that are difficult to understand. He grew up in Stamford, and as he said, his life was “formed there,” but he never really felt at home. Like many of us, he didn’t fit in. He found some solace there in writing verse and song.

The precocious intelligence and sensitivity which made life in the small West Texas town something of a challenge, began to work in his favor when he finally went away to school at Tarleton Junior College in nearby Stephenville in the late 1950s. There he discovered beer and some notoriety for his wit and music. One of the truly classic John Clay songs, “The Road to Mingus,” was a favorite among friends at Tarleton, who eventually voted him the coveted title of Ugliest Man on Campus.

In 1960, John enrolled at “The University” in Austin, Texas, still a fairly small, sleepy college town that also happened to be the capital of a largely agricultural state, with an emerging petrochemical legacy. In those days Austin was still deeply conservative, distrustful, and suspicious of nonconformist behavior. The powers-that-be regarded the little enclave at 29th and Nueces with special and decided interest.

Though under the ever-watchful eye of the Austin Police Department, something was being born there in that little West Campus scene that would later come to define Austin, at least for a time. Nascent elements that would help vitalize the distant San Francisco scene and have a profound effect on the whole country in decades to follow first came into being there. Music was a big part of the scene, and for John it was the perfect catalyst in the creation of a magic period of life that would frame much of his later art.

Although Austin had a long musical history, from the old days when fiddlers and banjo-players like Jack Meyers and J.D. Dillingham held forth at house dances to the later dance halls with Texas swing at places like Dessau Hall in the 1930s. There was country music at Big Gil’s Club on South Congress and the Skyline north of town on the Dallas Highway or in countless bars on the east side like Mary’s Place, the Victory Grill, and Charlie’s Playhouse, but it was the new generation of scruffy little hole-in-the-wall joints like The Fred, or The Library, the 11th Door, and the Id Coffeehouse that attracted folk singers and obscure half-cocked jug-bands like The Lingmen. Among these was the Angel Band with John Moyer, Lanny Wiggins, Powell St. John, and Janis Joplin.

Kids from the Ghetto and the College House crowd and old rent houses scattered west of campus made the nights come alive in these little upstart venues. They would eventually also reach out to venerable musicians like Bill Neeley and Jesse Ashlock who occupied a special place in the scene as did Mance Lipscomb and fiddler Teodar “T-olee” Jackson and his son TJ from the St. John’s neighborhood. On-campus folk-sings branched out far to the north out to Threadgill’s gas station way up on North Lamar.

Lanny Wiggins, Powell St. John, and Janis Joplin formed the Waller Creek Boys in 1962.

Lanny Wiggins, Powell St. John, and Janis Joplin formed the Waller Creek Boys in 1962. Janis played the autoharp and sang sometimes in a high, pure, almost angelic voice even while she was developing the powerful raging style that better suited her public image and would eventually propel her disastrously to wider fame.

But in those days the Waller Creek Boys played real traditional folk music, not the corporate claptrap that came to dominate the commercial face of the era (later to be so effectively lampooned by the Cohen Brothers with their masterful satire in the film A Mighty Wind).

No, John and his friends sought out and played sounds from the root and branch, from the way music was before corporate capitalism and its apish legions finished co-opting the cherished tunes and songs of the American people and molding them into plain genres of a neutered, named, and marketable class of harmless commodities. In the Ghetto they managed to stay pretty close to the place music had come from.

Its residents that summer included Janis Joplin, Powell St. John, Lanny and Ramsey Wiggins, John Clay, Tary Owens, Wally Stopher and his brother Tommy and Tommy’s girlfriend Olga, and several other people who came and went.

Part of our good time was Friday night fish fries at the Ghetto. One of the residents was a fellow named Don Kleen, who loved to fish. On Friday mornings he would take a cane pole, hike down to a spot on the Colorado River called Deep Eddy, and fish all day. In the evening we would gather under the huge shade trees in the packed-earth yard of the Ghetto and eat what Don caught, washed down with cold beer.

The Waller Creek Boys would get out their instruments — Joplin played the autoharp at the time. John Clay would pick up his banjo, and we would all sit back under the trees and listen to the music, singing along on the choruses. Clay had two songs he would render in a high, whining voice: “On the Road to Mingus,” about a fatal drag race between Mingus and Strawn; and another one about a woman named Brenda whose husband ran around. We never tired of hearing them.

— Lonn Taylor

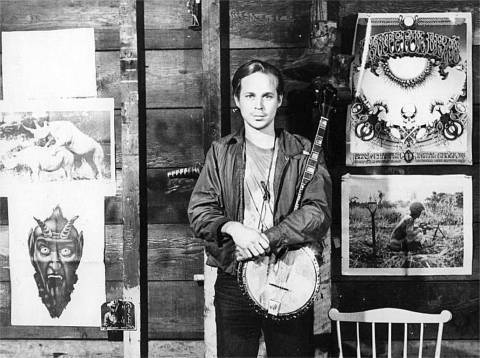

No constraint could ever prevent John Clay from setting down his own vision in song.

Forces sought to work against the emerging scene, to constrain and control the potential of its subversive experimentation. But no constraint, however placed, could ever prevent John Clay from setting down his own vision in song. That he did so with such deep authenticity, such unexamined fealty to the very breathing soul of tradition sets him apart from all the “songwriters” who have claimed Austin as home in the intervening years.

From an edition of Austin’s underground newspaper, The Rag, in September 1968:

Rag: Why haven’t you joined an electric rock group?

John: I believe in banjo.

Rag: What is your political position?

John: I’m a decentralist of some kind and it enrages me and gives me an unbearably helpless feeling to see huge depersonalized forces try to fit Austin to some kind of standardized mold. They have already done this to the suburbs. That’s just a good place, like a sort of reservation, to keep all the suckers. I think the American middle class is a great, huge herd of suckers and the American way of life is trying to develop these suckers like you would develop a bigger and better breed of milk cow. They expected me to become a contented cow, but they got a goat instead.

Those early Austin years are stories I have only heard. I didn’t find my way here from Brazos County until the mid-seventies. But, thanks to the Austin Friends of Traditional Music, whose Sunday open mic sessions at the Armadillo Beer Garden often featured John with the Lost Austin Band, I got the opportunity to sit transfixed by the words to “Gotta Get Away,” “Digging Up Camp Swift,” or “The Ballad of Roger Baker.”

Over endless cups of coffee with the late and much lamented Leo Sullivan, I learned several versions of the secret history of my adopted town. John was Leo’s twin star and in talking with John (if that’s the right word for it) over bad coffee at Les Amis in those days, and listening to the words of his songs, I gained an impression of that earlier time which will last the rest of my life.

John Clay and Janis were an explosive pair, fun but more than a little dangerous.

According to Leo, John Clay and Janis were an explosive pair, fun but more than a little dangerous. Constantly feuding, they both “spoke in the imperative and were both pig-headed.” Janis would steal milk bottles for the deposit to buy booze when living in the Ghetto. Neighbors would try to chase her down, to no avail. Her favorites were Southern Comfort and ”tequila sandwiches” … that is: lime, booze, lime…etc.”

Leo Sullivan was John Clay’s friend. They first met in a coffeehouse folk music cafe called the Purple Onion. I guess you might say that Leo came to be the manager of the Lost Austin Band. He knew the value of John’s unique gift and took it upon himself to seek out musicians who might prove worthy of being members of the LAB.

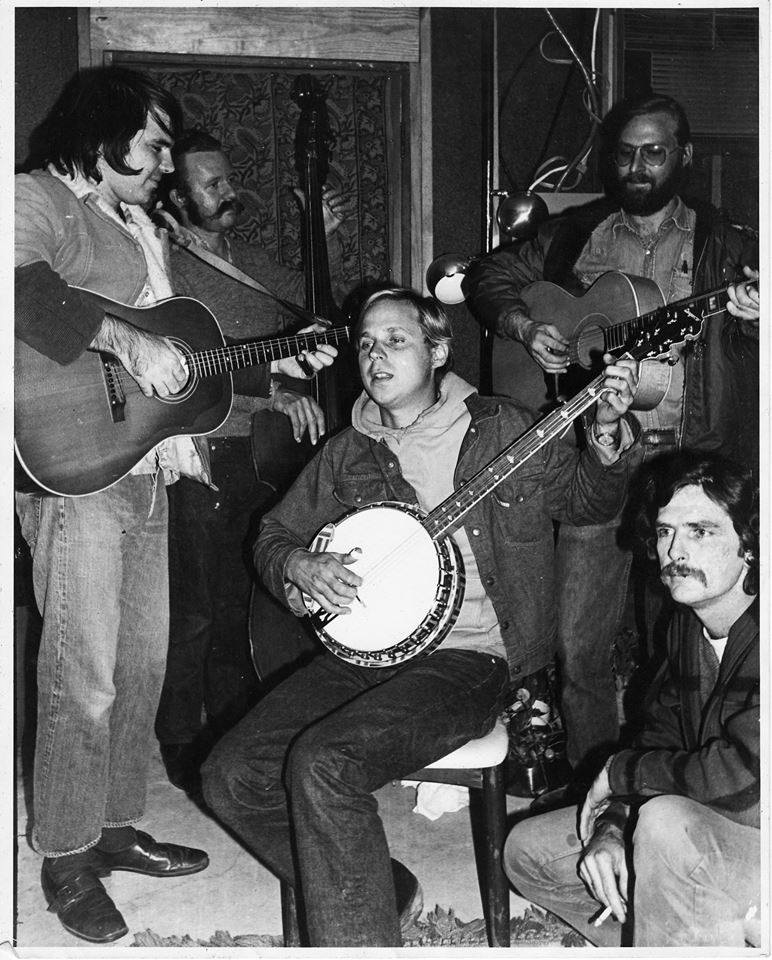

Perched at his favorite table, the best vantage point for inspecting life along the drag in his favorite hang out, Les Amis restaurant at 24th and Nueces, Leo strategically recruited for the band. The Lost Austin Band consisted of John on banjo, Douglas Tabony, violin, Gary Smith, guitar, Ted Samsel, accordions, and Johnny Moyer on the bass. John Farr played guitar for a time with the band. Mike Farmer replaced John Farr in 1973 and in the late ’70s Jon Polacheck joined the band on Dobro.

The LAB played at the bi-monthly meetings of the Austin Friends of Traditional Music as well as various venues around town. The first AFTM meeting site was in the Armadillo World Headquarters (inside at “The Cabaret” and in the Beer Garden). The band released two albums — “Drifting through the 70s” (1980 on Mockingbird Records) and “Bad Boy Come Home” (1983 on HiFi Nance Records). Both long out of print, but soon to be available again online.

“One road’s just as good as another

When you’re looking for a place that you can’t find.

— from “The Fifties Song”

Almost all of John’s songs were about real things. Real events. Real people. Real bits that make up history only if they are written down and remembered. He had a deep understanding of language, its descriptive power, and strong opinions about the purposes toward which that power ought to be directed. Much of his writing captured history that might otherwise have slipped beyond recall.

“I went to Hattie’s about half past ten and the madam said well come right in.

We know you here by your first name.

You’re a victim of the evil dissipation blues.

…

Now pusher’s in the alley, for thirty-five skins you get sixteen reefers and some heroin

They know me there by my first name.

I’m a victim of the evil dissipation blues.”

— John Clay, Powell St. John, Janis Joplin, et al.

The cooperatively authored song “Evil Dissipation Blues” is full of historical references that were still common in memory at the time, of places, like Charlie’s Liquor and characters like Hattie Valdez, 1903- 1976. Google that for the scraps you may find. Gathering such unnoticed and incidental occurrences of life further trained John’s innate skill to find the personal importance in world defining events of global impact.

“It was a very hot Monday. It was August the first.

The sun was barely over them when they heard the first burst.”

— from “The Ballad of Charles Whitman”

John was present when Charles Whitman started shooting people in a way that had

never happened before.

John was present when Charles Whitman started shooting people in a way that had never happened before. John had been giving banjo lessons to Tom Eckmund who was the first among those killed that day. Tom’s friend Claire Wilson was expecting. She and the child still in her womb were specifically targeted by that bastard shooting down from the tower. Of the three only Claire survived. John told the fullest story of that tragedy in his seldom performed ballad. It is a deeply moving, honest and awful account of what happened to all of us on that day.

Unfortunately, a failed songwriting clown was quick to dash off an embarrassing bit of musical tripe on the same subject at the time, hoping to pass it off as humor. Somehow that awful screed did manage to get air-play on local radio. John’s superb, desperately truthful and starkly beautiful account went unnoticed.

“Tom was hit next, the first one on the mall killed.

And Claire underneath him, lay very still.”

–from “The Ballad of Charles Whitman”

For many years the Lost Austin Band dependably, snidely, and effectively balanced John’s brilliant, erratic performances with a deftness that only true friendship could lend to the unpredictability of genius. Recruited by Leo Sullivan, the members of the band were selected by what I am sure was an inscrutable matrix of impossibly obscure qualifications.

The LAB rehearsals were legendary as much for the long stretches of conversation that separated each song as for the music itself. Leo recorded many of these sessions which are quite remarkable in several respects. Out of the mix of intense commentary, random observations and wild-ass theoretical constructs, came more inspiration, helping to focus the lens of John’s sense of the absurd on the things that were going on around them as Austin began to feel its growing pains.

“Oh the smog turns the hills into a fairyland.

Before it came, they were so very bland.

Now the landscape is coated in shades of grey

And the hills look just like mountains faraway.”

— from “The Mockingbird Song”

The changing landscape and societal impacts were strangely echoed in John’s intensely political and yet ideologically ambivalent way of seeing the world. Though he came of age surrounded by imperatives undeniably progressive in sentiment, he could never be counted on to tow the party line.

“See a middle-aged Latin, who’s way too thin

That’s how you know he just moved in.

Had to get away, no more work down there.

Well it had a nice climate,

But he couldn’t live on air.”

— from “Gotta Get Away”

Constant throughout his considerable work was an intense and unsentimental immediacy.

Constant throughout his considerable work (John wrote over 100 songs) was a sense of the present and the close-at-hand, an intense and unsentimental immediacy that in turn drove large-scale events and broad historical change, yet in his hands they remained personal, the shared heritage of a circle of friends.

“Now South Austin’s turning plastic

And I helped to make it so,

Cheap hippie labor built apartment row

And Chicanos too, with their wet-back crews

With Blacks and freaks, toppin’ off the roofs.”

— from “The South Austin Song”

With the passing of John Clay just before Christmas, and that of his singular counterpoint, Leo Sullivan, just one holiday before, Austin left an era many of us will cherish as long as we live.

In my 20-plus years as a host on KUT-FM’s now lamented Saturday morning radio program “Folkways,” I was lucky to welcome John Clay and the Lost Austin Band on the air many times. John’s music still stands out in my mind, among all the many gifted and talented artists now familiar as stalwarts in the history of Austin songwriting as the one worth remembering the most.

John’s music always reminded me for a couple of reasons of Charlie Poole and His North Carolina Ramblers, or A.P. Carter, or Walter “Kid” Smith, or Blind Alfred Reed — or maybe the very source, the musical ground from which those voices emerged; the long tradition of singers stretching back to the earliest times for whom events of the day in the towns where they lived were woven into songs, drawing the exegetic narrative from real life into common memory. He fits in that company.

He pulled the very stuff of daily life in West Texas into sharp focus.

Back in the 1950s, John was trailblazing the art of making songs. He pulled the very stuff of daily life in West Texas into sharp focus, recounting the gist in songs like “Morgan Williams,” “Highway Town,” or the lethal “Brenda.” He drew from his childhood memories of Dallas for the “Flying Red Horse.” Later as a proud subversive he prevailed and in the following decades was perhaps himself a catalyst for the changing times.

Ed Guinn remembers:

“John was a totem, a kind of touchstone of those years when I met so many of the people I now consider my oldest and best friends. John represented a way out from the closed and narrow world of “separate but equal” that I had grown up in. John was authentically eccentric.

…

Unlike my daily experience as one of 60 stick-out black kids among 25,000 whites at UT, thanks to John and others like him I was one of the gang. I was able to rent a roach motel room in the ghetto just like the other lucky kids (you know who your are), go to the corner and buy three quarts of Carling for a buck and throw a party complete with a live band, or at least a live John Clay complete with banjo.”

John’s songs chronicled life in Austin when it was becoming a place worth living in, and as it began to change.

Ballad of Wynn Pratt

Crowded Out

Harley Hogg

Travis Rivers

The Vic and Angie Song

The End of the Street

Funky Old Limestone Buildings

Don’t Nobody Know About Shiner

The West Mall Song

Every title was an entry into a cherished, often jaded, sometimes fatal aspect of life here in River City through the darkly innocent lens of a uniquely adapted observer.

John’s writing was topical, but not in the somewhat mercenary sense that came to characterize much of what was to be sold as the “folk boom” of the ’60s and the subsequent singer-songwriter craze. His art was not exploitative but emerged naturally from a deep and earnest connection between shared astonishment at events of the world, the uncertainties of our place in them and his ability to connect the two.

The joys of expectation and the inevitably human fate of disappointment come out in songs about the Ghetto days on Nueces Street, the birth of the scene in San Francisco, its disappointments, and the return to Austin. And about the loss which unstoppable change was bringing to the town that had given him hope:

Don’t Look Now

No Blade of Grass

The South Austin Song

East Sixth Street

Gotta Get Away

John had been swept along near the center of the free-wheeling cultural phenomenon that had begun to transform Austin.

John had been swept along near the center of the youthful, free-wheeling (if not care-free) cultural phenomenon that had begun to transform Austin. By the late 1970s the city had begun to see in itself things that those young freaks had been impertinently celebrating for years. Though the transition was not without struggle and even bloodshed in the tumultuous decades that were to follow its initiation, Austin began to think of itself as different from the rest of Texas. Weird.

“I fought the 50s, and I won.”

— Powell St.John

Several disparate aspects of life in Austin had just begun to converge around this new sense of itself at about the time John and other members of the scene began to feel the inevitable pressures of advancing adulthood and all that comes with it.

In 1963 John had married Judy Sullivan. Together they brought two bright and beautiful children, Johnny and Celia, to the world. John was a loving father, but the changing times, economic and personal challenges may have played a part in undermining the bonds that held the family together. The town was changing. Life was changing, but John continued to make songs about all of it.

“…And now those days are gone, and nobody cares

There’re freaks everywhere.

And the kids all have hair,

But, these times are too high-geared.

…

Oh, yes its weird, weird weird.”

— from “Weird, Weird, Weird” (1972)

John had an endless supply of theories about matters at every level. I am convinced he saw connections between things that maybe nobody else could. In his prime he had a memory like a steel trap and endless energy for ideas and talking (if that is the right word for it) about them.

I remember Leo showing me one of John’s old notebooks. It contained pages of seemingly random ordinary words written in longhand. They were, he told me, words that John had cataloged. Words that he could remember knowing before he was old enough to spell or write them. It was an exercise he found interesting and one beyond my ability to comprehend.

He wrote science fiction stories and prior to getting his degree in linguistics set out to see if he could create an entirely new written language. The furtive dictionary was found among his effects in the old school bus where he lived next to Leo’s ramshackle place out near the lake many years later.

Most amazing to me among his many types of songs, were the historical, decade-based epic ballads. Each was long (even for John), involved, insightful, funny and sometimes terrifying.

The 20s Song (about the days with his older brother)

The 40s Song

The 50’s Song

The 60s’ Song

Drifting Through the Seventies

Sins of the Fathers

I first heard John with the Lost Austin band when I came here in the mid-seventies and have never been able to get the sound of his voice out of my head… I am happy to say. I’m sure I’ll listen to his songs and learn from them from now on. My sweetheart Christy and I sing for sheer joy “Freaking at the Laundr-o-mat.” “All Our Weed is Gone,” or “The Texas Border Ballad.” In other songs, John’s words come back to me as catharsis, through tragedy and sorrow in works like the “The Anson Runaway,” or “Return to Florida.”

John never stopped making songs, right up

to his last days.

John never stopped making songs, right up to his last days. More funny ones like “Poor Old Quadaffi,” and “Lord, Deliver Us from Fruit Cakes,” and others like the one about his love of dogs and kids, the song “Buddy,” and even one serious reflection about September 11. Many of his songs shared a peculiar attitude, a singularly indefinable darkness of technique I can only describe as having a foreboding sense of humor that was in the end not always bereft of hope.

“I wake up unafraid each day when the sun rises.

Bad things are happening, but they are not surprises.”

— from “Grass Coming Up Through the Concrete”(1976)

Every day now I read the news and wonder what kind of song John would write about this event or that, from a newspaper story about the unsolved murder of an old married couple in our neighborhood or the collapse of oil prices and what’s happening to Russia, Spain, and Greece now.

“Did you know there’s people making plans for you and me?

And it doesn’t matter if you do not agree.

But when they make mistakes, you’re the one that has to pay

And they will still be making plans for you.”

— “Grass Is Growing Through the Concrete”

No one I ever heard could pull at the roots of a tragic event and link its essence back to our own lives with something less overt than irony but more compelling than plain humor. He had a certain ingenius, almost mystical equanimity that could hold two overpowering, contradictory emotions at once and turn them into song.

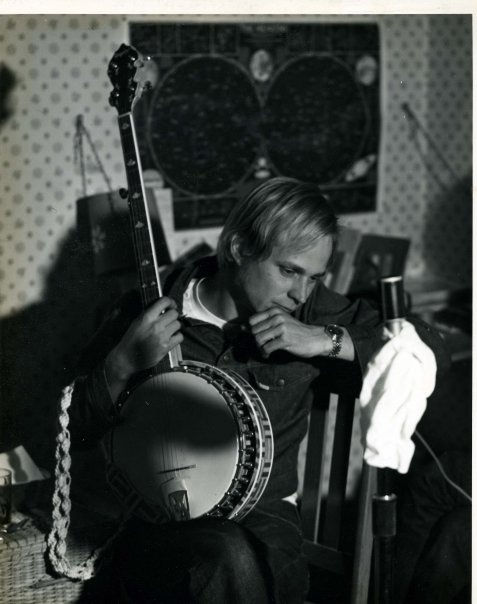

I loved to hear John sing. I loved his voice. I admit that it is an acquired taste. But once, back in the early ’80s at Maggie Mae’s before East 6th Street was “revitalized,” I was sitting next to a couple visiting from England. John was singing with the Lost Austin Band there. I think it was the “ATO Pledge Song” maybe, but he was gripping that banjo of his and singing good and loud with the veins popping out on his forehead. The British lady turned to me and said, in a serious way “Coo, he’s scaaary.” They stayed on though, to listen and I think they might have begun to catch on before the show ended.

The last days of life were hard, but I know John found happiness and true joy in the love of his children and grandchildren. I can’t say I knew John well, but I knew him for a pretty long time and I never saw him smile the way he did one afternoon visiting at our place when his little grandson Nick piped up loud and proudly telling everybody in the room how his granddad played the banjo!

I’d like to think of Leo and John continuing their life-long collaborative conversation somewhere up in a rambling hillside shack, secluded in a little-used and overgrown section of Paradise with coffee and smokes, but I guess I know better.

“I hear the clouds singing but they have been all along;

The heavens are ringing, I just now caught on;

And all of creation is outside of me.

I’m outside myself now, like I was meant to be.”

–from “I’m In the Other World”

See YouTube videos of “Road to Mingus,” “Millers Reel,” “Mockingbird Song,” “Laundromat Song,” and “West Texas Memories.”

Listen to Christy and the Plowboys, featuring Christy and Dan Foster, perform John Clay’s “Mockingbird Song,” “Morgan Williams,” and the “Texas Border Ballad” at ReverbNation.

Listen to Rag Radio’s all-star jam dedicated to John Clay and featuring Powell St. John, Spencer Perskin, Christy Foster, Susan Perskin, and Maryann Price. It includes a performance of Powell’s “John Clay.” Listen to it here:

[Dan Foster, who hosted “Folkways” for 20 years on KUT-FM in Austin, is a computer programmer by day, an old-time fiddler and tune-collector on his own time. Dan researches and writes about the early days of Texas music. Christy Palumbo Foster has been a musician and vocalist in Austin for some 40 years. She is a longtime fan of John Clay and the Lost Austin Band.]

I lived next door to John Clay in the Ghetto, briefly, in 1962. My room was the one at the end of the stairs; John’s room was off to the side, over a garage. Below me was Ted Klein, whom I knew from earlier, the beatnik days of The Place on 19th Street. I heard later that my room had been where Janis Joplin lived, but at the time I didn’t know who she was. I had been in Mexico since 1960 doing field work for my MA in Linguistics, and stopped over in Austin that Spring to finish my UT thesis before moving on to Chicago. The common interest in linguistics was what we talked about. My impression was that John took Linguistics courses to learn about English dialects, and to keep his speech authentic (maybe even to make it more so!).

Nick, thanks for your lucid comment. I doubt you remember me but you were a UT anthropology professor when I was an undergraduate anthropology major at UT. Many of us from the old crowd were (Powell St John, Tary Owens, Chet Briggs, E.K. Durrenburger, Elton Pruitt. Tommy Hester, and many others.) At that time anthropology represented one of the most liberating majors we could choose. John Clay and I go back to 1965. Together we formed the Lost Austin Band and recruited the other members with the invaluable help of Leo Sullivan around 1973. As you said, John was a linguistics major who was frustrated by the theoretical demands of the department at that time…… an unrelenting focus on descriptive linguistics and a neglect of what John was really interested in….. historical linguistics and glottochronology. Perhaps it is ironic now that the department lost its identity and became merged with today’s very large anthropology department at UT where performance studies with an important, Prague School historical bent predominate. As I am sure you are aware, all this has an important ideological foundation. I should leave this for another day however. Poor John struggled at UT because his stubborn, iconoclastic views were not popular with Lehmann and other department figures. Later in the 70’s, he tried his hand at Journalism and graduated. But the only job he could find was a frustrating job at a small town, East Texas newspaper. He quit that in short order and came back to Austin where we hooked up musically once more. Together we stuck it out in Austin together until 1980 when Archie Green pulled me off the stage at the Rome Inn and talked me into going back to graduate school in Anthropology at UT. I graduated with a PhD in 1991. But John and I along with the band remained intact….. We made two albums together and the group even swelled from 4 to 6 members. In 1989, I left to do a year’s worth of dissertation fieldwork in Dominica, West Indies. When I returned to Austin, I found the band in a semi-defunct state and it dissipated slowly after that into nothing. But, thanks to Dan and Christy Foster’s intense and sustained promotion of John’s legacy, I feel the best is yet to come and I hope our shared history will not die aborning. I taught anthropology for 10 years at Austin Community College, retired last June and moved to St Thomas, USVI. where I have reconnected with my old friends from Dominica. I might teach one or two classes at University of Virgin Islands but I will have to wait until the Fall of course. Thanks for reading this rather long-winded account.

Best, Dr. Gary Smith

Dan & Christy Foster have been a wonderful treasure trove of tunes, songs and history, and really ‘fostered’ a love of John and his songs in me (and my wife as well). So interesting to find linguistics as so much of a common thread…

“Austin, Texas, back in the 1950s would seem like a really weird place to us now. Conventional, conformist, deeply racist and, in step with the times — intolerant, suspicious and vengeful.”

Being born and raised in Austin, I’m not sure about the value of this description. I agree that those were characteristics of too many people, but Austin was for decades prior a university town and that had a profound influence on a significant segment of the population. My Dad was a university professor, so perhaps that unduly influenced who I became, but I had many other friends whose fathers were not associated with the university who still joined with us in the later 1960s counter-culture.

I greatly appreciate your piece – well done and a fitting tribute to one of Austin’s many wonderful musicians. Thank you!

Dan and Christy, what a wonderful and well-written article. Thank you for taking the time to compose and share such thoughtful observations and memories about Daddy, his songs, and his friends. The first time Nick (my son) and his cousin Jack (my sister Celia’s oldest son) saw someone sing Harley Hogg live (as opposed to the album cut) was when you both played it at your house while Daddy sang some of the verses with us–they will always remember that when they think of their granddad. And thank you, Thorne, for publishing the article.

Beautiful, deep, heart-felt tribute, thank you so much for this! John always seemed to me like a throwback to the Depression, like those old black and white photos of starving farmers’ kids. I, too, loved his voice; I’d already acquired a taste for Bob Dylan’s when I first heard John; not that much different.

One day sitting in the UT Chuck Wagon with a bunch of people, John came walking in eating something he held in his hand and somebody, maybe Leo, called out, “Hey John, whatcha eatin, an apple?” John turned his hand around to show his treat as he answered laconically, “Nope, peyote.”

And so it was…

Thanks is not enough for Dan Foster’s very nicely-written tribute to John Clay. John and I both shared that belief in the decentralized American society for years. We differed when his views drifted to the Right and made for a very spirited debate between us. However, it never got in the way of our friendship. Like my former, late mentor, Archie Green, I was (and still am) a convert to “antidisenstablishentarianism” but John and I had a mutual respect for each other’s views and a shared disdain for the way our society was developing.

It was an honor and a pleasure to publish this excellent piece of writing by Dan and Christy. It’s beautifully crafted and pays fine homage to an important and unique force in Austin’s cultural evolution. I consider it to be a significant contribution to history.

I do, however, join Richard Jehn in questioning the characterization of Austin then as being “Conventional, conformist, deeply racist and, in step with the times — intolerant, suspicious and vengeful.” A minor quibble, but I think it may slightly overstate the case.

It was certainly a more conservative, conformist, and conventional — and often mean-spirited — time, and not only was there strong prejudice exhibited against those of color — but also against those of us who simply let our beards grow out and our hair grow long!

But Austin was also a beacon to folks around the state who harbored liberal, questioning, even rebellious views. I know I felt the city’s draw from the time of my youth — and got here as soon as I could.

In the late ’50s Austin hosted an active civil rights movement and it was an early center for opposition to the Vietnam War. Well before the days of the ghetto, Austin was home to a community of iconoclasts, seekers, peaceniks, peyote eaters, and literary and political rebels, and there was always a progressive undercurrent at the University of Texas.

That said, the seminal role played by the raggedy denizens of the Ghetto — and other post-beatnik enclaves around the west side of campus — was undeniable. And it drew the attention — and the ire — of the local constabulary. The following comes from an article I wrote for the Texas Observer entitled “The Spies of Texas,” about spying by the UT (and Austin) police on (and harassment of) local radicals and iconoclasts:

“Much of the material in [UT Police] Chief Hamilton’s files centers on early Austin countercultural figures, musicians and literary types, especially those associated with the ‘Ghetto’—an old wooden Army barracks in the 2800 block of Nueces on the west side of campus that was home and/or home base to much of the hipster cognoscenti. The police also seemed focused on the activity of the staff of the Texas Ranger, the campus humor mag that incubated a number of major artistic and literary talents….

“Janis Joplin numbered among those that the police associated with the Ghetto. In one entry, beside her name are scribbled the words ‘…suspected of bringing in amphetamines, Dexedrine, etc.’ Other members of the Ghetto crowd mentioned in the files are musician Powell St. John, who would be a pioneer of the San Francisco psychedelic rock scene; cartoonist Gilbert Shelton, who was to create the iconic Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers strip that appeared in The Rag and other underground papers all over the world; and the late William Brammer, a former Observer editor whose book The Gay Place would be recognized as perhaps the finest novel about Texas politics…

“As for the Ghetto group in general, the files read that they ‘float from place to place. Start and end at times at Gilbert Shelton’s, (or the) Unitarian Church.’ In another notation: ‘Peyote and drugs used in wild parties on Fri and Sat night. Most of the wild crowd members of the Ranger staff.’…

“‘There were so many different groups that came together during that time: artists, writers, activists, musicians, motorcyclists, humorists, dope fiends, cavers, chemists—iconoclasts who came together on civil rights, the war in Vietnam, and their right to be themselves,’ remembers Pepi Plowman, a part of the Ghetto crowd whose name appears in the files. ‘The UT cops just saw all this as a threat.’

“The police used this notion of a threat to justify constant harassment, much of which involved drug busts and rumors of drug busts. Because many of those targeted were nonstudents and lived off campus, it was often the Austin police who did the dirty work. And sometimes perceived harassment was more creative: According to Clementine Hall, who was married to lyricist and jug virtuoso Tommy Hall of the legendary Thirteenth Floor Elevators, ‘at least twice, city fumigation trucks pulled up to the back of the Ghetto and sprayed pesticide directly on us.'”

Sorry. I got a little carried away here! Anyway, here’s a link to that article at the Texas Observer site: The Spies of Texas.

And never forget the pioneering musical legacy of the late and great John Clay!

Well, interesting to learn more of this individual and his life. However, I witnessed him act in a strange way I’ve never forgotten since.

When I was at UT the hostage crisis with Iran erupted and all around were spontaneous “hate Iran” rallies on the Malls, both east and west.

This older guy, rather wild-eyed and ranting on the west mall tower steps, nonetheless was erudite in the sense that he rattled off numerous Koranic verses with full citations, in order to show that Islam was bloodthirsty, cruel, and implacably violent against infidels.

He was inciting the crowd into a murderous fervor, preaching a ‘clash of civilizations’ before it was popular (Samuel Huntington, Ann Coulter, various apocalyptic evangelicals).

I walked away, shaken, fearful for some Iranian students I had personally known to be gentle, good people not deserving of any hateful diatribes.

To my great surprise, I came home to my rental later that afternoon to see this same man mowing the lawn.

I asked his employers who this was & they told me he was John Clay and a musician, bohemian, etc who could not possibly have been a hater. They were convinced the whole performance I’d witnessed must have been for satire.

If so, even purely as a dramatic performance it was a chilling evocation of the worst of what both nations were feeling in those days, & a precursor to much of what unfortunately has happened since.