Letters from France I:

France’s greatest gift to America

was our independence

By David P. Hamilton / The Rag Blog / May 19, 2011

[This is the first of a series of dispatches from France by The Rag Blog‘s David P. Hamilton.]

PARIS — Tea Party types love to bash France and worship the “Founding Fathers.” The historical reality makes this a perfect example of their ignorance. Without France, the American Revolution would have failed and the U.S. would have been a British colony for at least several decades longer.

Besides that, the “Founding Fathers” were a bunch of francophiles. Franklin, Jefferson, and Madison were all delighted to serve as American ambassadors to France, Washington incorporated Frenchmen into his General staff, and Tom Paine rushed off to join the French Revolution.

If one polled Americans about what was the most important gift France had ever given the U.S., they would probably say French fries, which actually came from Belgium. The more well-informed would more likely respond that it was the Statue of Liberty. While not wishing to denigrate that monumental work of art, the best answer would be independence from the British Empire. Without France, the 13 colonies would not have won the American Revolutionary War.

Those who have any knowledge concerning France’s contribution to American independence would likely point to the Marquis de Lafayette who was indeed an important military leader of American forces. Having been made a Major General at age 20, he commanded American troops in numerous successful engagements and was a close aide to General Washington.

But actually, there were hundreds of such French volunteers; men like Brigadier General Du Buysson des Aix of the North Carolina militia, Major General Louis Le Begue de Presle du Portail, Brigadier General Preudhomme de Borre, Major General Philippe Charles Jean Baptiste Tronsoin de Courdray, Brigadier General Tuffin, Marquis de La Rouerie, Brigadier General Jean Baptiste Joseph Laumoy, all serving in the American Continental Army, and Captain Pierre Landais, commander of the frigate “Alliance” of the Continental Navy.

Colonel Teissedre de Fleury was the only foreigner serving in the American army to ever be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. But individual French volunteers were just the beginning, icing on a much larger cake. They were not the crucial element.

One cannot understand the American Revolutionary War without understanding that it took place in the context of a long struggle between France and England. As a result of the Seven Years War (1756-63), France suffered considerable losses, including its North American colonies, Canada and the Louisiana Territory. Over a million people died in that war and the French navy was decimated. France remained bitter over these losses, reorganized its military and sought a means to recoup and to weaken its perennial rival, Great Britain.

When the American Revolution broke out, France had little confidence in its success. It did, however, allow individual young Frenchmen to join the American cause, including Lafayette. The ship that carried Lafayette and several other volunteers to America was bought with funds provided covertly by the French government. Early in the war France authorized the clandestine provision of military equipment to the American colonies.

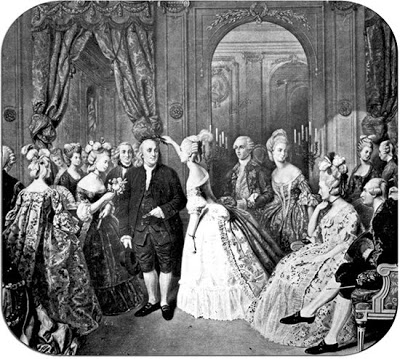

Benjamin Franklin arrived in Paris as the American ambassador in late 1776 to seek French aid and was highly successful, becoming a phenomenon at the court of Louis XVI in the process. In October 1777, the Americans won the Battle of Saratoga, which convinced the French that the Americans could win.

In February 1778, Franklin signed a Treaty of Alliance with France. In response, England declared war on France the following month. They fought each other not only in America, but also in India, Africa, and the West Indies. Aid to the Americans from the French government had nothing to do with support for democracy. They were merely exploiting ways to diminish Great Britain.

Much of the costs of the American Continental Army were paid by France. But the biggest contribution was the participation of the French military, both regular French army troops and the French navy. Most notably, in early 1780, 6,000 French troops landed at Newport, Rhode Island under the command of General Rochambeau who had 40 years of military leadership experience.

After several months debating strategy with Washington, a plan to move south to attack the forces of British General Cornwallis in Virginia with the support of the French fleet under Admiral De Grasse was agreed upon. This was Rochambeau’s plan. He had conducted all the arrangements with De Grasse. Washington had wanted to attack New York, but his plan was essentially overruled by the French.

Unfortunately, while on their way south the American troops mutinied in Philadelphia over not being paid. The French picked up the tab and they moved on.

The decisive battle of the American Revolutionary War was a naval engagement between the British and French fleets, the Battle of Chesapeake Bay in September 1781. The French won. The British fleet retreated to New York. American naval forces were not involved. The defeat of the British fleet meant that Cornwallis had no means of escape from Yorktown, located on the end of peninsula. He was surrounded and outnumbered 2 to 1 by French and American troops on land and the French navy on the water. His defeat was only a matter of time.

Although fighting at Yorktown continued until October 17th, the British surrendered 8,000 men after only sustaining at most 300 killed. But their situation was hopeless and they were raked with dysentery. There were more French troops at Yorktown than American, not including the French naval personnel or individual Frenchmen fighting with the Americans. Some estimates say the disparity was as great as four Frenchmen to one American. French casualties in the battle were twice those of the Americans.

A contemporary observer described the French and American forces present at the surrender. “Among the Americans, the wide variety in age — 12- to 14-year-old children stood side by side with grandfathers — the absence of uniformity in their bearing and their ragged clothing made the French allies appear more splendid by contrast. The latter, in their immaculate white uniforms and blue braid, gave an impression of martial vigor despite their fatigue.”

Yorktown was the last major battle of the war. American independence was recognized by Great Britain at the Treaty of Paris in September 1783 as a direct result of the British defeat there.

Ironically, the war had been triggered by British attempts to make the colonists pay for their own protection, England being in dire financial straits as a result of the cost of the Seven Years War. After it was over, the cost France incurred in support of the American cause led to the bankruptcy of the French monarchy, which contributed enormously to triggering the French Revolution in 1789.

Such profound unintended consequences seem common in floundering empires in decline. The U.S. squandering a trillion dollars in the Iraq War is a prominent case in point.

[David P. Hamilton has been a political activist in Austin since the late 1960s when he worked with SDS and wrote for The Rag, Austin’s underground newspaper. Read more articles by David P. Hamilton on The Rag Blog.]

What Mr. Hamilton says is undoubtedly true and should never be forgotten. But before we get to all teary-eyed in favor of contemporary almost-institutionalized anti-froggyism, it should be remembered that eighteenth-century Drance's main goal was curbing the power of England. Very, very helpful, yes; altruistic, not too much.

Bravo, Dah-veed!

Woff: dude, he said exactly that in the article.

One point that might illuminate these events further for some: on these shores, the "Seven Years War" became known as the "French & Indian War", and later the historical setting for the famed "Leatherstocking" novels. British troops, colonists, and their Native allies were