From Freakence Sixties:

A Letter to The Rag

By Didier Mainguy / The Rag Blog / July 29, 2009

It’s difficult to express some feelings and concepts in a foreign language. When writing in English, I’m feeling like an idiot. (I mean more idiot than I am really)

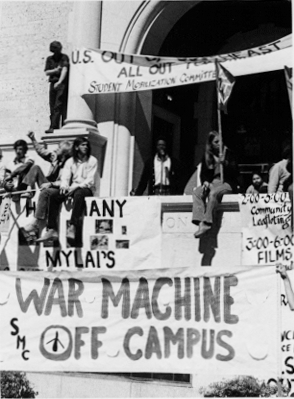

I’m proud and honored to see a link with Freakence Sixties on The Rag home page. For about 10 years, I’m collecting information and documents about the so-called sixties in the US. My story is your story is History, you know.

Eric Noble, the digger archivist, wrote “To assure that our history survives the inevitable tendency of revisionism, it’s critically important that we grow our own versions of what happened and why.”

Nicolas Sarkozy, a few day before being elected, expressed the will to eradicate the spirit of 1968.

We do not cope only with a “tendency to revisionism” but with an attempt to erase the very memory of a decade of revolt. The message is “no alternative.”

I do agree with Marcus Del Greco when he says “Digitization of Thought is Preservation of Thought,” The Mind Mined Public Library.

Here is our first task, I think – Struggles are ahead.

Our second task. I’ve no definitive belief about this decade in the US and I will probably never have. I’m more interested in learning some lessons for the future.

I’ve been in touch with many people in the US and I’m surprised that rivalries and resentments still exist after all these years.

Two main points make me uneasy about the sixties:

Think Globally, Act Locally. Robert Pardun wrote “The movement was, after all, the combination of thousands of local movements each made up of individuals … It was on the local level that the strategy and tactics for reaching new people were developed and where the connections between the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement, the women’s and other liberation movements, and the counter-culture were forged.”

First, I’m unable to see any significant connection between the local movements during the sixties, except for the underground press (UPS and LNS).

Second, the blue collars seem to be absent from the decade, with some occasional exceptions (e.g., The Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement). I’ve read a lot about the so called generation gap but what about the class gap? Or to quote David Farber’s The Sixties From Memory To History:

Protesters paid little to no mind to the history of white working people in the United States — conceding little to their struggle to make ends meet and to create meaningful lives in fast changing times. They seemed to give no respect to the hard work it had taken and still took most Americans to earn the modestly pleasant life-styles they had chosen for themselves.

What protesters seemed to offer in the place of the rewards of hard work, in the minds of many Americans, was talk — the free speech movement, the filthy speech movement, participatory democracy, chanting, singing, dancing, protesting.

I’d like to hear from you about these points. I don’t know if this blog is the right place. You’ll decide.

Keep on keepin’ on.

Didier Mainguy

Freakence Sixties

I believe that there was a failure to link our struggles with those of working class people. There were exceptions – Farmworkers solidarity, occasional local union struggles. Generational struggles are by definition temporal. That isn’t true of class struggles. The U.S. ruling class has been highly effective in obliterating class consciousness. More later…Alice

Didier — thanks so much for your commentgs and for your work in preserving the true histor(ies) of the 1960s! Re Pardun’s comment on local movement connections, you are correct in that few of those connections clearly resulted in non-local organizations, e.g. UPS & LNS brought together a number of independent local publications into a national news network. However, I would argue that MANY of the organizations that sprang up during the era, whether to address specific crises or ongoing issues, grew through exactly the sort of personal contacts Pardun describes.

Some of the groups were of short duration. Deacons for Defense and Justice began in Alabama among blacks who wanted to defend their communities against violent racist attacks. A chapter was founded in Austin in about 1965 after a visit from Alabama activists. I believe tghat the original Deacons were eventually subsumed into the Black Panther Party, but for several months we raised funds for them on campus, with the slogan, “Every dime buys another bullet.” As I recall the Alabama activists came to Austin because a white civil rights activist they knew, who had worked in Alabama, was then living and working in Austin, Dick Reavis.

I think what Pardun is getting at in the passage you quoted is simply that we tended to hear about, and perhaps join or support organizations more on the basis of knowing people who were already involved than on the basis of objective analysis.

Re the lack of links with the working class, well, first, yes to what Alice said; also, many US college students of the 60s were the first of their families to seek a higher education — we came from the working class but we weren’t supposed to go back to it; we were supposed to reach a higher level and it was for this purpose that our parents were sending us to college. I think this gave many people kind of a split view of their own ultimate self-interest. The late Gregory Calvert’s theories of the New Working Class were perhaps the most determined New Left effort to resolve this contradiction.

As it turned out, the contradiction was quite illusory, and would not have been possible in a culture that retained a strong class awareness. Whatever “profession” the graduates of the late 1960s and 70s have pursued, and whatever professional accolades they have accumulated, the enormous majority of them have worked longer than 40 hour weeks during their entire careers, and their labor has profited others more than themselves. Ask one of them the difference between a weekly wage and an annual salary and they may well reply, “A warm bucket of spit!”

warmest regards!

Alice’s recollection is correct. Counterculture people actually went into some factories and asked the workers to revolt and leave. The workers did not accept their advice, and there was great hostility between labor and the counterculture. This is where the GOP got the idea of identifying progressivism with rejection of the culture. Remember the speeches Agnew wrote for Nixon. Then, in the early seventies, the Democrats embraced what was called the New Politics, which left out labor and white ethnics.

What a tragedy, but the GOP think tank folks exploited all this perfectly.

Then in the 1970s began a massive cultural crusade to convert people to purely materialistic values. It was led by the thrust for market fundamentalism. Unions were seen as counterproductive. It was matched by a very self-centered–hence materialistic in the Hegelian framework– form of religion, and it blossomed as the Christian Right, with aqn auxiliary in among the traditionalist Catholics, led by politician/bishops.

That mindset became the heart of our national culture. It could have been otherwise. Read Pacem in Teram and compare it with the Port Huron statement. They had far, far more in common than anyone could believe.

I’ve been in a public sector union (TSEU) since 1979 (even retired) and it is that organization that pushes back against privatization, cuts to public services, threats to retirement & health care benefits. May Day and International Women’s Day both have their roots in U.S. labor struggles, but most Americans don’t even know that. It’s actually immigrant workers here who know that history and remind everyone during their May Day mobilizations. Didier, do you think that the 60s generation in Europe stayed connected to working class struggles? The students and workers were certainly allied in Paris in April of 1968.

Thanks for your comments

Alice, the “sixties” in France were quite different for various reasons..Notably the strength of the French Communist Party at that time. The relationship between students and workers was complex because their different expectations (caricaturing, radical social changes for the students, better working environment and wages for the blue collars). In june 1968, The FCP and the unions accepted the pay raise and called for the return to work . For the students,(and a minority of workers) it was a betrayal. Students and workers were rarely allied.

Sherman, you’re probably making reference to the 1969 “silent majority speech”. De Gaulle pronounced a very similar speech in june 1968 and the conservatives called the “silent majority” to a huge manifestation in Paris.

The tactics are very similar (and still works) : Isolate the dissidents , inspiring fear in the public opinion. And the working class was (is?) mostly conservative. About gender, feminism, races, long-haired……

The issue of the relationship between radicals and working class is universal and still topical.just as the connections between the local grassroot movements. I’m fellowing with great interest the new SDS, and its ability to build a non authoritarian, decentralized, multi issues movement.

I’ve not a clear perception of the rôle played by some leading figures and their impact on the local movements. (Leary, Kesey, Hoffman, ….) A former digger said to me “there were lots of strong male egos that could barely stifle the bristling hairs when they entered the same room.”

The movement has disappered very quickly (in its original form) and I see a correlation between the withdrawal of most of these leading figures (on a local and national level) and the colapse of the movements. (Was it A Movement?). The newcomers was more followers than actors.

What got me started?

Thanks Mariann.. I didn’t know Greg Calvert.and your poetry is great

Long Life to The Rag.

Didier