The Rag Blog was inspired by an underground newspaper we published in the 1960s in Austin. We called it The Rag. When Carol Neiman and I were editing The Rag — and many more whose bylines you see here from time to time were also involved with that heady undertaking — we also worked with SDS and were totally immersed in the sixties New Left uprising, organizing against social injustice and the War in Vietnam.

At the same time, Stoney Burns was editing a fellow underground paper in Dallas and Ernest McMillan was a leader in the civil rights struggle there, working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC and SDS were fraternal organizations. And for those of us active in the movement in Texas — where we were the underdogs! — you can bet we were all brothers and sisters in the struggle.

You know where we are now. Here’s an update on Ernie McMillan and Stoney Burns.

Thorne Dreyer / The Rag Blog / November 4, 2008

SNCC activist McMillan and underground newspaper editor Burns reflect on those days of turmoil and change.

By Roy Appleton

“Is this Stoney?” says the smiling man, crossing the threshold to hug his guest. “Hey, brother.”

“I bet you didn’t expect the gray,” says Stoney Burns.

“I got it too,” replies Ernest McMillan, leading the pony-tailed visitor into his East Dallas apartment and back to the past. Living now less than a mile apart, they hadn’t seen each other since those restless times. Not since the days of war in Vietnam, protests and assassinations, culture clashes and civil rights struggles, of Black Power, Flower Power and women’s liberation. When something not exactly clear was happening.

Tightly ruled, convention-numbed Dallas — still stung by the tragedy of Nov. 22, 1963 — was relatively tame for a big city in the 1960s. A vigilant police force helped see to that.

But as the peace and justice movements gained momentum elsewhere, they found voices here as well.

As in young Ernie McMillan, passionate foe of prejudice and war. And Stoney Burns, one playfully aggressive, seriously stimulated newspaper editor.

On separate paths, they would rouse and rattle in ways their hometown had never seen.

“Dallas was just outraged by Stoney,” said David Richards, one of his attorneys. “He represented everything they perceived to be evil.”

While Mr. McMillan set a tempo for activism to come.

“We owe a priceless debt to him,” said the Rev. Zan Holmes, a longtime Dallas pastor and social activist. “He stood up and spoke up. He called attention to the problems and became our inspiration.”

Cutting the head off the beast

“Seems like there was a lot more life. This is depressing,” says Mr. McMillan, soaking up some South Dallas sights and sounds near Martin Luther King and Malcolm X boulevards.

He has returned to a center of the action back when he led the local front of the national Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

“We’ve got Freedom Fashions, not freedom and justice,” he says, driving through a land long waiting to bloom.

He sees stability along Meadow Street and fondly remembers Dr. Charles Hunter and his Hope Presbyterian Church, home now to a service agency for girls.

“We had a lot of mass meetings, community meetings here.”

Blocks away, at the corner of Pine and Malcolm X, he parks outside an abandoned building, long-ago home of an OK Supermarket.

“Looks a lot smaller than it did then,” he chuckles, standing near a rotting overhang. “Man, I don’t remember this.”

He talks of his group’s protests and boycott of the white-owned grocery chain, says it stocked inferior products at bloated prices.

“We would have people marching around the building with signs,” he says. “People would get off the bus and join us.”

He doesn’t talk much about the night of July 1, 1968, when he and an associate, Matthew Johnson, led a group into the store and left behind $211 worth of destruction. “We just went in to send them a message,” he says.

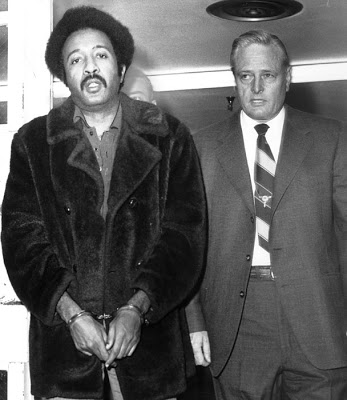

In less than two months, the two young African-Americans were arrested, tried and dealt 10-year prison terms by an all-white jury. The charge: Destroying private property worth more than $50.

The store owner’s son testified he saw Mr. McMillan drop a gallon bottle of milk and Mr. Johnson smash bottles of grape juice and a watermelon. Jurors heard a defense attorney liken them to the American patriots who dumped English tea in Boston harbor.

“They were making a political statement,” said attorney Vincent Perini, recently explaining his analogy. “They were standing up for the folks in South Dallas.”

Jurors also heard a prosecutor call the pair “revolutionists” helping rush civilization “to hell at a hundred miles an hour.”

The rush was on Mr. McMillan, said Don Stafford, a retired Dallas assistant police chief, at the time a police lieutenant in South Dallas. “He was a thorn in their side, and they needed to get rid of him.”

And they did, says Dr. Hunter, visitation pastor at Oak Cliff Presbyterian Church. “They were cutting the head off what they thought was the beast.”

Going against the grain

For the budding Ernest McMillan, a 1963 honors graduate of Dallas’ Booker T. Washington High School, war and racism were beasts.

After withdrawing from Morehouse College in Atlanta, he registered voters and demonstrated in the South before bringing his passion and training back to North Texas in 1965.

After briefly enrolling and protesting at Arlington State College (now the University of Texas at Arlington), he established a Dallas chapter of SNCC, then growing more militant.

“It was the way I was raised, to not abide injustice, to not be quiet in the face of wrongdoing,” said the son of a family steeped in ministry, medicine and teaching, reared near the Dallas Freedman’s Cemetery.

The SNCC cadre was hardly the first or last to oppose racism and discrimination in Dallas. The Progressive Voters League began organizing black voters in the 1930s. Protesters challenged segregation at the State Fair of Texas in 1955. Freedom rallies in 1961 called for boycotts of department stores and movie theaters.

Demonstrators picketed the whites-only Piccadilly Cafeteria in 1964 and marched for civil rights in 1965. It took a lawsuit and the courts to establish the current city election system. The fight for Dallas school desegregation lasted almost 50 years.

The efforts and influence of Felton Alexander, Juanita Craft, Richard Dockery, Kathlyn Gilliam, Elsie Faye Heggins, J.B. Jackson Jr., Al Lipscomb, Maceo Smith and the Revs. Peter Johnson and S.M. Wright and other local African-Americans have long been recognized.

The Revs. Wilfred Bailey, Mark Herbener, William McElvaney and Rabbi Levi Olan were among local clergy working for peace and equality in the Sixties and later, while attorneys Ed Polk, Frank Hernandez, Fred Time, Mr. Perini and Mr. Richards have been leading defenders of civil rights.

But few local black leaders had a radical, confrontational — edge in the late Sixties, Dr. Hunter and others say.

“There was definitely a sense that you stay in your place. You’ve got yours,” he said.

That wasn’t a concern for Mr. McMillan and his group of 30 or so. He, Matthew Johnson, Edward Harris, Michael Dodd, Fred Bell and the others would organize, mobilize and speak out with a fervor jolting to some. Beholden to none.

And working outside the system, they drew the system’s attention.

Mr. McMillan tells of traffic stops and searches. He smiles about the police officer seen going through his trash, and the one found eavesdropping in his back yard.

“They were trying to disrupt us, keep us off balance,” he said, recalling how his guys joined in, following officers and recording their actions.

The young agitators were hassled “no doubt about it,” said Mr. Stafford, the former police officer. “If you were against the establishment you were going to get harassed.”

No, police just tried to “keep the peace” and contain troublemakers during and after the SNCC years, said Paul McCaghren, a patrol captain in 1968 and later the department’s intelligence director.

“We didn’t want any problems, and we were really sensitive because of President Kennedy being assassinated” here, he said.

But some officers weren’t sensitive enough, Mr. McCaghren said. “Could we have done a better job? Oh, yeah,” he said. “We were reverting to the old police theory that fear is the best deterrent you have against violence. So we weren’t using dialogue and we made a lot of mistakes.”

In time Mr. McMillan was gone and his group fractured. Three weeks after his grocery conviction, he was indicted for draft evasion. Authorities said he refused to take an induction oath, an allegation he denies.

“I was cursing, belligerent, all this stuff. A lieutenant pulled me out of the line, said look now we’re going to let you go home, cool off. We’ll send you another [induction] letter.”

Freed after posting bond, he traveled to Connecticut in June 1969 to address a church group. While there his attorney told him he could be arrested for leaving North Texas. He fled, was captured in Cincinnati in late 1971, returned to Dallas and sentenced to three years in federal prison after pleading guilty to violating terms of his release.

Before his sentencing, and until stopped by the judge, Mr. McMillan read part of a statement in court, saying the draft charge “reflected … the systematic attempt to remove me, by any means necessary, from the political activities” of his group.

The draft charge was dismissed. An appeal of the supermarket case was rejected. And he spent three years and two weeks behind bars.

An era of tension and change

Dallas didn’t have the riots, destructive firebombings and mass arrests. Not even a tank in the streets. Still, the late Sixties was an eventful time in the city.

Residents in 1968 began loosening the business community’s grip at City Hall. The Dallas Citizens Council had selected and successfully backed City Council candidates for years. But voters changed the city charter, adding two new council seats. Months later George Allen would fill one of them, representing South Dallas, as the council’s first elected African-American.

In 1968, marchers in South Dallas, including Mr. McMillan, supported the Rev. Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign. Downtown, Ruth Jefferson, Mr. McMillan and other and protesters occupied the state welfare office demanding better benefits; others picketed the selective service center.

Dallas police opened neighborhood police centers to promote racial harmony, and the city’s Block Partnership program began connecting poor families and churches. A human relations commission would convene in 1969.

Groups such as the Dallas Committee for a Peaceful Solution in Vietnam, sponsor of Saturday vigils at Dealey Plaza, kept speaking out against the war.

“It was pretty heady stuff. We were trying to save the country,” the late Ken Gjemre, an organizer of the vigils, said in a 1999 interview.

City leaders and police braced for rioting after Dr. King’s assassination on April 4, 1968.

“We were expecting trouble. We had a lot of people on the street, and we didn’t want them to get a jump,” Mr. McCaghren recalled.

He had an officer keep a log of police activity during those times. It tells of heightened alerts throughout the city, anonymous calls about suspicious behavior and unfounded threats to bomb Love Field and city hall. It also reports that two lighted beer bottles with kerosene were thrown at a white-owned convenience store in South Dallas: “One started a small fire. … Both fell about 20 feet short of the building.”

Four months after the assassination, the City Council gave the mayor authority to impose curfews and other actions against civil disturbances, a move denounced by ministers and black leaders.

With the city preparing for mass detentions, the Dallas Bar Association asked members to help with any legal proceedings, recalled Vincent Perini, who said he offered his services.

“They wanted people to serve as prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges,” he said. “It was going to be a sort of makeshift tribunal. It was a wild time.”

Concerned about decorum downtown, the City Council in 1967 restricted gatherings at Stone Place, the walkway between Main and Elm streets — now home to mostly restaurants, then a hangout for street preachers and those hippie types.

So the peace people and others began gathering at Lee Park, near the counter-culture’s Oak Lawn center of gravity, for music, rallies, the high life and perhaps a dip in Turtle Creek.

Their looks and outlooks drew scorn from the mainstream, including the city’s two daily newspapers’ editorial pages. Their “pot parties” and illicit economy made news. As in this January 1968 report in The Dallas Morning News:

“Police raided a hippie pad in North Dallas shortly before midnight Saturday, rounded up 13 booted and unbarbered boys and girls,” and “enough marijuana to make 140 cigarettes worth $1 apiece.”

Other stories told of stiff prison sentences for drug convictions, such as a Dallas man’s 50-year term for selling $3 worth of marijuana.

And the News tried to help readers with a series of articles – Drug Peril in Big D – “outlining the problem in all its startling aspects.”

Dallas Notes

“Free Ernie.” A poster in Ernest McMillan’s apartment delivers those words with a drawing of his smiling, bearded face.

“I believe I took the photograph that this was taken from,” says Stoney Burns, eyeing the memento, as the reunion takes another turn.

He also splashed the drawing across the cover of Dallas Notes, for his newspaper’s Sept. 18, 1968, issue. An accompanying story, headlined SNCC Members Shafted, told of the OK Supermarket convictions.

It wasn’t the first or last article about Ernest McMillan or courtrooms to appear in what would bring Mr. Burns local celebrity and notoriety.

Launched in March 1967 to “tell the truth” about Southern Methodist University, Notes from the Underground — first produced on a Texas Instruments copy machine — would mushroom into Dallas Notes. And for almost four years, the biweekly paper’s alternative news services and ever-evolving staff would tear into those swirling times with a clear bias against war, intolerance and hypocrisy.

“Notes is the boss, the only fearless, wide awake, red-hot newspaper in town,” crowed an early advertisement for a publication that would peak with street sales of about 12,000 copies per issue.

The paper’s anti-war stories included “profit and loss” statements listing area companies’ war contracts and names of the local dead. Its reports on politics and dissent often had an editorial ring. “Elections Don’t Mean [expletive],” headlined an elections issue. “Our Power is in the Streets.”

Notes tried to mobilize its readers, calling in early 1968 for the boycott of an Oak Lawn Avenue waffle shop. People “with long hair, beads, boots, flowers, beards, etc.” weren’t being served, the paper reported, urging readers to “mark the date on your calendar: Flower Power can work in Dallas.”

The paper covered the area music scene and printed reviews, letters, cartoons, short stories and poetry. It kept tabs on the local drug trade, from arrests to user-friendly how-to’s.

And with a spicing of four-letter words and porcine portrayals, it wrote about the men in blue. Such as those who showed up at Stone Place on May 20, 1967:

“Over a hundred Dallas hippies tried to have a love-in last Saturday,” Mr. Burns wrote in his first bylined story. “Unfortunately, about twenty paranoid cops had a hate-in and, baby, they had the guns.”

That article “plunged Dallas into the sixties,” wrote James McEnteer in his book Fighting Words, Independent Journalists in Texas.

A graduate of Hillcrest High School and the University of Arizona, Mr. Burns – then known by his given name, Brent Stein – joined the newspaper while working for his father’s Dallas printing company and advising an SMU fraternity.

Introductions to marijuana and LSD had engaged him. He offered to help editors Doug Baker and Nancy Lynne Brown with their graphics. And while photographing a peace vigil at Dealey Plaza, the obscene taunts of American Nazi Party members moved him.

“I didn’t like seeing people abused like that,” he recalled, wiping a watery eye. “I definitely wasn’t an activist until then. But that was the breaking point.”

He wrote for the paper as Stoney Burns, the name he goes by today. “I had a straight job and didn’t want my customers to know,” he said.

His battles with police began when he was removed from downtown for selling the paper. SMU banned it in October 1967. He became editor two months later. And as Notes turned up the heat, so did authorities.

An October 1968 cover story about Dallas’ pornographic movie industry featured a photograph with bared female breasts.

Twice the next month, police raided Mr. Burns’ communal home and Notes office at 3117 Liveoak St., arresting him and others there, while hauling away newspapers, typewriters, cameras, telephones — everything used to produce the paper. With rented equipment, the staff kept publishing.

“That was the ploy used to shut down his newspaper,” said lawyer David Richards, who sued the police chief and others on Mr. Burns’ behalf.

Federal judges in Dallas decided the state obscenity law being used against the newspaper was unconstitutional. On appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled federal courts had no place in the dispute. But by then the obscenity law had been rewritten and the charges against Mr. Burns dismissed.

“We had a great day, sitting on his porch, watching these angry police officers having to return his stuff,” Mr. Richards said.

Court orders later targeted two other supposedly obscene issues — after they had been widely circulated. One featured the frontal photo of a nude male at a Dallas parade of miniskirted women. A particular cartoon aroused some outrage as well.

“We got a lot of mileage out of that. It was fun,” said Mr. Burns, telling of the time television cameras documented officers ripping the cartoon from papers. Its most explicit panel dominated the next issue’s cover, but with numbered dots in place of lines and an invited headline: “Hey Kids! Just connect the dots and you too can be arrested.”

Mr. Burns was among those arrested at what Notes dubbed the Lee Park Massacre, a melee involving police and “hundreds of boisterous youngsters and hippies” (as The Dallas Morning News put it) on April 12, 1970.

Witnesses say a crackdown on swimmers in Turtle Creek started the ruckus, and officers blamed Mr. Burns for inflaming passions with obscenities and police death calls, a charge he did and does deny. “Too bad they didn’t kill you,” a prosecutor reportedly told him in court before his conviction for “interfering with a peace officer.” Sentenced to three years in prison, he was cleared on appeal.

Mr. Burns quit the paper in September 1970. It would fold early the next year. “There was too much pressure — my court date, making payroll,” he recalled. “I had to get rid of it.”

Months later, he was art director of another Dallas underground paper, the Iconoclast, and soon back in trouble, for helping photograph an undercover narcotics officer outside a Dallas courtroom. He received six months in jail for contempt of court but again was cleared on appeal.

He ran for Dallas County sheriff in 1972, leaving the race after being busted with marijuana. A jury gave him 10 years and, at prosecutors’ request, one day in prison for the almost one-tenth ounce of pot police found after stopping his van. That extra day made him ineligible for probation, but after changes in state law made possession of small amounts of marijuana a misdemeanor, his sentence was commuted.

Mr. Burns served 19 days and was freed in December 1974 — in the same week as Ernest McMillan.

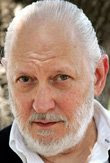

Mr. Burns returned to the print shop and his music magazine Buddy, ditching the dissent, but not his humor. He sold the magazine years ago, but now publishes a business advertising booklet.

Never married, 65 and Medicare-free, he lives in a house near Lower Greenville Avenue, where his days include music (mostly bluegrass), some television and friends. The wild curly black hair of youth is now a silvery gray, the once-scraggly beard trim and white. His underwear-only Frederick’s of Hollywood parties are long gone, but he will hit a bar or concert or (as Notes would hail it) “that harmless, non-addictive herb known as marijuana.”

“When I do I always say, ‘Why don’t I do this more often,’” he says with a smirk over a soft drink at a neighborhood dive.

Mr. Burns says he hasn’t cast a ballot since weighing in for Lyndon Johnson in 1964 and won’t break his streak this year. He attended an anti-war rally in Dallas before the Iraq invasion, but has no interest in firing up the outrage — or even messing with police.

“I just can’t do what I could then. It’s just too much trouble,” he says.

Still, he offers up remembrances from the days when he was, like it or not, the face of the local hippies.

“Stoney was a quiet, mild Jewish guy,” said Fred Time, his lawyer in the Lee Park case, who employed him for a spell as an investigator. “He had this underground paper and somebody labeled him king of the hippies. He was just a pot-smoking young guy trying to find a niche.”

Back then the rush of change and sense of possibility liberated some, threatened others.

Notes tried to inform and energize the young, “get Dallas to loosen up” and have a good time in the process, the editor says.

And to those ends, the effort was an unregrettable success, he says, shrugging off his part in it all.

“I was young and dumb and thought I was bulletproof,” he says. “But I wasn’t that much different from a lot of people in the movement. I was just the messenger.”

Still, “it was fun to see the straights freak out,” he said during a return visit to the SMU campus, where he recalled being routed by police for selling newspapers. “They said I was inciting to litter.”

Room for improvement

After prison, Ernest McMillan became an aide to then-state, now U.S. Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson. He organized a prison-justice project before moving to Houston, where he founded a program to empower young inner-city males.

Back in Dallas, the 64-year-old grandfather remains an adviser to the Houston program. He volunteers at his church, Munger Place United Methodist, the Dallas Peace Center and with Pastors for Peace, among other gifts of time.

“I’m still evolving, trying to aim my arrow at the mark,” he says during a morning break.

He is not bitter about his clashes with the law. And he gives his SNCC days an OK — not a KO.

“We turned on some switches and lights, got some people off their butts and into voting booths and off their knees praying and into the city hall chambers, fighting for justice,” he said. “I’m not regretting it, and I’m not beating my chest about it.”

He and his group deserve credit, said Ms. Johnson.

“Those young people had the nerve to talk about it publicly.” And by bringing “attention to the inequities” facing local blacks, she said, “open access came much smoother than it might have.”

Despite “some positives,” much work remains in South Dallas, she said. “When you come home you don’t see a whole lot of changes. It’s depressing to see that as we move in, often the quality moves out,” she said.

Mr. McMillan barely recognizes the neighborhood of his youth, now Dallas’ upscale Uptown. He sees some advances in southern Dallas, but much room for improvement.

African-American families and neighborhoods are more fragmented, he said, but “there’s been no fundamental change from when I was around in 1968.”

What’s needed are organizations that “can sustain themselves and carry on the struggle” — groups always drawing in youth, he says.

“I want young people to know they have tremendous power, tremendous energy, tremendous resources within them, and they just have to flip the switch on and use it.”

Source / Dallas Morning News / Posted Oct. 25, 2008

Stoney Burns died 4/29/11 of a massive heart attack at Baylor hospital in Dallas

RIP Stoney

Do you know where I can see old covers of Dallas Notes Magazine?

Please see:

Thorne Dreyer / James McEnteer : Dallas Underground Icon Stoney Burns Dead at 68