The blue afterwards:

Mourning for Marilyn, Part III

By Felix Shafer / The Rag Blog / January 13, 2011

Part three of three

[Marilyn Buck — political prisoner, acclaimed poet, former Austinite, and former original Ragstaffer — was paroled last August after spending 30 years in federal prisons. But, after only 20 days of freedom, Marilyn died of a virulent cancer.

In the first part of this essay, Felix Shafer wrote about the pain of losing his friend and artistic collaborator to cancer, and his determination to mourn her in some way appropriate to her life, accepting and experiencing grief as fully as great friendship demands.

In part two Felix discussed the specific criminal charges for which Marilyn Buck served nearly 30 years in federal prisons, demonstrating that her acts were actually specific responses to the repression of Black and anti-imperialist activists across the country.

While many today dismiss such acts as adventuristic and self-defeating, the consensus among Black activists, especially members of the Black Panther Party and others who have themselves been victims of government repression, is that Marilyn Buck was a principled freedom fighter. While Marilyn’s thinking on tactics certainly changed over time, her commitment to human rights and equal justice never wavered.

Facing an 80 year sentence, Marilyn had to come to grips with life inside the walls. Until the end of her life, she refused all attempts to treat her case as special, but identified with and walked the same paths as thousands of other incarcerated women. Their daily struggles for simple dignity became her field of endeavor, and fodder for her creativity.

Shafer recalled Marilyn’s emergence as a poet, fighting to maintain her own humanity in the spirit-crushing prison environment. As the so-called “free world” hurtled onward to the distressing present, for a growing community of friends and supporters on the outside, Marilyn Buck, from a steel cell, became increasingly “our breath of fresh air.”

— Mariann G Wizard / The Rag Blog]

keywords: a revolutionary who dreams like a poet

The 21st century opened up and Marilyn was finding her own way towards a style in which humor, theory, art and the ironic began to dance with her politically radical common sense. From this dynamic a momentum grew within her, which allowed for tremendous personal change.

For the long-term imprisoned revolutionary this can be an agonizing process. It is incredibly difficult to risk overturning dogmas, re-examining cherished beliefs, while taking responsibility for how your actions — for better and worse — define you.

There is the repressive State power, not as an abstraction but an everyday presence, which studies each political prisoner’s psychology — emotions, vulnerabilities, moods, doubts, questions — in order to determine pressure points to exploit.[1]

The continuing goal, long after any hope of getting politicals to give up “actionable intelligence” (to further repression) was gone, becomes to break the resister so s/he will repent and discredit human principles of liberation. To have broken the imprisoned revolutionary’s soul is a key objective of the authorities because any healthy counter-example to their total power is threatening.

On this battlefield, and make no mistake it is a battlefield — a last ditch of significance — political prisoners, like Marilyn and her comrades, must be on the alert against psychological destabilization. Deeply questioning ideology, strategy and tactics in conditions of isolation (and political prisoners are often kept isolated from each other) and, in periods when the struggle is at very low ebb, is a risky and painful journey.

This long excerpt from Marilyn’s incisive and raw essay, On Self Censorship[2], reveals some of the way she thinks — with feeling.

Women are subject to censorship in a very distinct way from men prisoners. There is a disapproval of who we are as women and as human beings. We are viewed as having challenged gender definitions and sex roles of passivity and obedience. We have transgressed much more than written laws. We are judged even before trial as immoral and contemptible — fallen women. For a woman to be imprisoned casts her beyond the boundaries of what little human dignity and personal right to self-determination we already have…

It becomes difficult to maintain personal relations because all forms of communication are subject to total intervention — all under the guise of security. We have no privacy — our phone conversations are recorded, every word we write or that is written to us is scrutinized, especially as “high profile prisoners.”

Being locked up is physically and psychically invasive. All body parts are subject to physical surveillance and possible “inspection.” Never ending strip searches… one must dissociate oneself psychically, step outside that naked body under scrutiny by some guard who really knows nothing about us, but who fears us because we are prisoners, and therefore dangerous; political prisoners, and therefore “terrorists.”

The guard stands before the prisoner, violating the privacy of her body, observing with dispassionate contempt. It affects each of us. There is a profound sense of violation, humiliation, anger. It takes an enormous amount of self control not to erupt in rage at the degradation of the non-ending assault. I do not think I will ever get used to it. However, being conscious political women enables us to understand and articulate the experience in terms of the very real psychic censorship.

Every time I talk on the phone I have to decide what I will say. I refuse to let the government know how I really am; but I do not want to cut myself off emotionally either. How can I keep saying, “Everything is fine”? It is not believable; and, it would promote the official position that these high-tech prisons are fine places, especially these maximum security prisons with their veneer of civility. It would be a declaration that no, there are no violations of human rights here. It is a dilemma.

I express my interior life in poetry when I have the wherewithal to put the lines down… I write a letter and reread it. I clench. I have a crisis of judgment about whether to send it as is. Should I say this? I do not mail the letter that day. By the time morning arrives again I decide to rewrite it. To couch my thoughts in vaguer terms. Will my vagueness and abstractions frustrate the reader?

I feel like I am diffusing, becoming abstract. I am censoring myself. Like a painter who disguises her statement in an abstract play of colors and forms on canvas… Only she is certain of the voice that is speaking and what she is conveying. And if the observer misses what is being said?

Self-censorship is an oppressive, but necessary part of my life now. For more than six years it has infringed upon my soul, limiting, constraining self-expression. Yet, it is a studied response — a self-defense — against the ubiquitous, insistent, directive to destroy our political identities, and therefore us.

keyword: artist

Marilyn is one for whom the word revolutionary is truly earned and, yet, it’s also far short of encompassing. She was a woman with probing interests in the arts, culture, and natural sciences. She was a wordsmith who loved to sink her hands into the clay, making ceramic art that she sent out to people all over the country.

Marilyn was a prolific writer: well over 300 poems along with scores of essays and articles, which were widely published both inside the U.S. and abroad. Her master’s thesis became the translation of Christina Peri Rossi’s, State of Exile, published by City Lights in 2008. She won prizes from the international writer’s organization PEN and published the chapbook, Rescue the Word, and the CD, “Wild Poppies,” in which she (via phone recording) joined celebrated poets reading her work.[3]

In late 1999, together with Miranda Bergman and Jane Norling, artists and comrades she’d known since 1969, Marilyn formed surreal sisters — a trio to explore art-making and surrealism. This informal group continued doing art, studying, and occasionally writing, for nearly 10 years. In an unpublished (collective) 2003 essay, “Coincidence in Three Voices,” Marilyn writes:

Three of us had been sister political activists, friends, housemates in the late 1960s and early 70s. Miranda and Jane were artists and activists. I was a political activist who had not yet discovered artistry, at least for myself. By the time the three of us convened in the visiting room of the Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) at Dublin CA I had my artist self, though it had taken me half my lifetime to realize that I was and needed to be an artist.

Three women, I behind steel gates and triple barbed wire, Jane and Miranda outside, both painters and muralists. What could we achieve as women dedicated to creating new visions, a new world through collective imagination?

As a prisoner, I feel flattened, forever categorized as only a prisoner — nothing more. I want to scream I am not one dimension of a box, a box inside of a box! What shall I draw to express this?

When I think about Marilyn Buck, I see a revolutionary who dreams like a poet.

One paradoxical feature of the “obvious” is that not everyone takes the time to see it. We nod our heads at some outline, then say, oh I already knew that, and move on. So, at the risk of stating the obvious: under the most restrictive of circumstances, Marilyn continued to throw herself into processes of human transformation.

Becoming an artist — and being an artist is always a process of becoming — was very much part of her destiny. She was neither a propagandist nor a left wing copywriter — though she could fulfill these functions when she felt called to do so. Her art making was valuable in, of and for itself.

Art is a particular area of freedom: a disciplined work/living space of engaged feeling, thinking, and doing. Arts come to be created and live in a transitional space between self and others that is at the heart of all human cultures.

Confined in prison, Marilyn was able to use art-making to express a full range of feelings, desires and relationships that became her powerful, alive response to the death-driven system in which she was forced to exist. Her great capacity for hard work was channeled into highly productive and creative pathways.

She loved this part of her life and had plans to continue the creative work of writing and translation after she was released from captivity. There was the novella she’d begun writing. Skilled in the arts of translation-a bridge building art par excellence-she was working on a translation of Christina Peri Rossi’s work: Desastres Intimos.

When you think of Marilyn Buck: the revolutionary

I hope you also discover Marilyn Buck: the artist

From late 2007 to a month before her death Marilyn was involved, with a few of us on the outside, preparing her selected poems for publication. The idea for the book began in conversation with Raul Salinas, a great advocate of Chicano and Native American resistance, a former long-term federal prisoner, poet, and writer who passed away in Austin in February 2008.

The volume, tentatively titled: Inside Shadows[4] is a collective labor of love that we all believed would widen her readership beyond the label, “prisoner poet.” Together we daydreamed plans for a public launch and readings. The last letter I received from Marilyn came about a month before she died when she was very ill with little energy left for work. It was pure Marilyn: an engagingly lucid three pages of comments and revisions to the book’s table of contents.

keyword: She who links us

Beneath the distorted balance sheets of credit card, mortgage and International Monetary Fund debt, after the loan sharks and the default dreads have been (momentarily) cleared from our mindset, there remains a debt between Marilyn and her communities that isn’t about money at all. It’s my belief that Marilyn’s commitment to human solidarity with freedom struggles of Black and other (neo-) colonized peoples on the global plantation, with women and all who are oppressed, was her genuine effort to help balance the scales of justice in a world thrown terribly out of joint by empire.

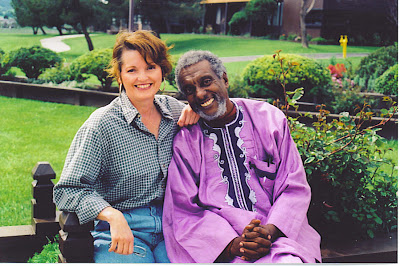

Over the years and, it seems especially these last months, some people have compared Marilyn to the anti-slavery warrior John Brown. The first person I ever heard say this was Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael) who visited Marilyn in FCI Dublin and corresponded with her. At her Bay Area Memorial on November 7, 2010, former Black Panther and member of the San Francisco 8 Hank Jones spoke movingly of her as a John Brown of our time. At her memorial in Harlem, a number of Black revolutionaries honored her with this comparison.

The essence of their point is not whether she played a comparable historic role but that she was one of the all-too-few who fought shoulder to shoulder with the Black movement. In speaking about white allies in the freedom struggle, Malcolm X called on people to fight like John Brown. It is in the historic context of what was the largest upsurge for Black liberation since the Civil War, that veterans of the Black struggle honor her today.

Along with John Brown, there is another older, historic personage who comes to my mind when I think of our sister Marilyn. This is a near mythic figure of someone we, in the left, don’t talk much about: The woman Antigone, whose story was dramatized thousands of years ago in ancient, classical Greece.

Briefly, Antigone was a young woman of privilege who was part of the royal court. Her two brothers slew each other in a conflict over the fate of the kingdom. The king decreed that the body of one brother, who had opposed him, must lie in the dust to rot and not be given decent funeral rites. Antigone — following an older just tradition — defied the king’s command and buried him — thus providing him entry into the afterworld. She dared to act and broke what she considered the patriarch’s unjust law.

Under interrogation her sister begged her to lie and deny the act in order to save herself. This she would not do. Antigone’s punishment was to be entombed/buried alive in a cave without food or water until she starved to death. The citizens had great sympathy for Antigone and the king’s son loved her. Fearing for the legitimacy of his rule, the king had his soldiers open the crypt but it was too late. Antigone had chosen to take her own life rather than die by starvation.

Through the ages, Antigone has been a symbol of women’s resistance. I believe that by representing collective struggle with thought-through programs for liberation, Marilyn stood on the shoulders of Antigone.

If Marilyn links you in your own way, as she does me, with time’s rich legacy of freedom struggle — she also links us with our losses.

Questions of who she was for/with each of us, how she lived, what she tried to accomplish and what commitments were willingly shared, must neither be quickly resolved nor stubbornly avoided. The work of mourning involves, along with other things, how each person finds meaningful answers, individually and with others, to the question of what Marilyn’s memory and spirit calls us to do and be. I feel that this is what honoring her legacy means.

For now, the traumatic circumstances of Marilyn Buck’s final year make all this exceedingly difficult.

When she died, some months before her 63rd birthday, she had served a total of nearly 30 years behind bars. The last 25 years were a continuous long march from arrest/capture in 1985 to her release in mid July 2010. Severely weakened by cancer, she finally left the prison camps and was able to live among us, outside the wire, for 20 days.

During this time Marilyn visited with a lot of dear friends, supporters and family. She got to embrace some of her co-defendants who’d been released years earlier. She spoke on the phone, corresponded by email with more, and was cared for by deeply loving people among whom were my daughters, Ona and Gemma. As she has been for the past quarter century, her close comrade and attorney, Soffiyah Elijah, was a constant protecting presence.

There’s just no getting around the great misfortune of her life’s ending only 20 days after she left that federal prison system which had held her continuously under the gun since 1985. Her will power was enormous and to remain vitally alive it had to be.

Can we even allow an hour to extend our imagination towards all the wonderful everyday things that she hoped to be able to do? What it would mean to be able to eat a good salad, to sit in the park, to spend as much time as she wanted with whomever she wanted, to walk outside in moonlight, to go dancing?

She could stretch out in her own home; one that wasn’t controlled by heavily armed state authorities. She was thinking about what kind of j-o-b might work out. Marilyn’s family, people in the Bay Area and around the country, political prisoners and social prisoners with whom she’d spent much of her life, all expected her long internal exile to end in celebration and happiness. Above all. Above all this. Marilyn wanted to live.

She’d been thinking about how to heal herself from the chronic, complex stress of prison and what she wanted to accomplish with her life. In other words: during the early part of the last year and a half, Marilyn had begun allowing herself to really believe that she was finally getting out.

I think sometimes that even those of us who do prison work and have visited political prisoners over many years may not always consider how difficult it can be, for people enduring very, very long sentences in hardened institutions, to dwell on their past and/or the future. No matter how many visiting rooms I enter, there is a real gap between people who live inside the wall and those of us outside. The weight of what has been lost and will never come to be can build melancholy and despair in the healthiest of hearts.

So when Marilyn could finally dare to consider what taking her dreams towards a real future outside might mean — many of us felt her exhilarating gust. As political supporters and friends we had an emotional stake in her freedom and in her victory over the FBI and Bureau of Prisons. This national political police-prison regime, so central to the deep, permanent state structure of Empire, has never stopped trying to break her and the more than 100 other U.S. political prisoners down.

I can feel Marilyn resisting the hint of any effort to make her heartbreak and suffering special by reminding us that

what’s happening to me is what happens to thousands of imprisoned women and men who get sick in the system… remember that there are 2 million people caught somewhere in the prison-industrial complex — if you’re going to write about me, remember I stand and fall with them.

Even as a release date of August 8, 2010 came into range, Marilyn’s medical symptoms were emerging with force. She was acutely aware that other political prisoners with legally sound parole dates had, at the last minute, been denied release due to political pressure and legal trickery.

One of the well-known agonies of imprisonment is that medical care — as it is for millions of the non-insured — is often atrocious. I live in California where the state prison system, which holds nearly 200,000 people, has been under a court appointed special receiver for years because of woefully inadequate medical facilities.

Political prisoners with life threatening illness have faced foot dragging, neglect, and worse from their jailers. Lolita Lebron spoke about the severe medical abuse and radiation burns suffered by Puerto Rican Nationalist Party leader, Don Pedro Albizu Campos, when he was held in U.S. prisons more than a half century ago. My dear comrade, Black Panther/BLA political prisoner Bashir Hameed, who died of cancer in 2008 was, at one point, assaulted by police in his hospital room.

From her own experience, and knowledgeable of the cruel battles other political prisoners have waged for treatment, Marilyn was constantly forced to weigh how to effectively advance her health care needs before a totalitarian administration adept at both routine and calculated neglect.[5]

After MANY months of worsening symptoms during which she regularly requested and insisted on evaluation/treatment AND WAS DENIED, she finally received a cancer diagnosis around New Year 2010. Major surgery followed about three weeks later and Marilyn reported that she was told the doctors were optimistic that they’d removed the malignancy.

To my limited knowledge she had no follow up scans or any professional post surgical care by her doctors for well over a month. It’s difficult to see how this can be said to meet any standard of acceptable medical practice. She received help changing her postoperative dressing from fellow prisoners. The Bureau of Prisons was very slow to diagnose her. They were slow to move and treat her. On March 12th she was informed the cancer had metastasized to her lungs.

Very early on the morning of March 13, 2010 — the day of the Spark’s Fly gathering in Oakland (an annual event organized by women to support women political prisoners) which drew nearly 500 supporters from around the country to celebrate her impending release and the dawn of a new life — I was one of the friends she called to tell the devastating news. In only six months time, plans for life after prison turned into a last ditch battle to survive and get out at all.

Soon thereafter, Marilyn went to the Carswell federal medical facility in a suburb of Fort Worth, Texas. She would be transported from this medical prison to a local hospital for cancer treatment. Two women who she knew well were also being held at Carswell and they helped her very much.

Miranda and I were able to visit Marilyn in Texas on May 1, 2010. We spent time together on Mayday and the next. Marilyn said, “if it was up to my will, I’d have this thing beat.” Gaunt and fatigued she used oxygen to help with breathing. She held herself with that incredible dignity and steadiness all who know her have experienced.

Marilyn said, “so many women here are medicalized into the role of patient and the setup here is about making us this way. I do not want to become this. I think about how my mother kept herself out of the hospital until nearly the end because she didn’t want to become like that.” She went on to confirm that, “In the eight weeks after surgery in Stanford (Stanford University in California) when I had no follow up tests — the cancer ran wild.”

She was very very sick and we could see with our untrained eyes that this was a battle our elegant sister was unlikely to survive.

The question of government’s role in Marilyn’s death is in the air. It merits a real discussion about whether and how we might hold the state responsible for its (mis)treatment of her. This stark tragedy and rupture of hope has led some to believe she was killed by the government. Others dismiss this way of looking at it as conspiracy theorizing and paranoia. I have heard people, including former political prisoners, express either of these opposing viewpoints.

In a way this process parallels the anger and sadness I feel. Saying “they did it” mobilizes rage against the system, honestly recognizing the very difficult prognosis of people with leiomyosarcoma, even under the best treatment situations, brings me to powerlessness and great sorrow. Ultimately, while this polarized way of looking and feeling is not so helpful, grieving — for me — involves allowing myself to go through all of it.

We do know that living for long periods in hostile institutional environments of deprivation and stress degrades the immune system, damages emotional well-being and can shorten the lifespan. Marilyn respected her doctor in Texas, felt that she had her best interests at heart and was giving her the right chemotherapy treatment. We do know that a stress-free, loving environment, excellent diet and adjunctive treatments were not available. We do know that personnel at Carswell made cruel comments to her expressing “surprise” that she was still alive.

Last year, during the many months prior to her diagnosis, when she was working through her own channels to get the administration to act, Marilyn didn’t want her supporters to launch a public pressure campaign. I know that during the summer and fall of 2009 when this possibility was raised, her response was to tell us to wait. She was concerned that such a mode of action could be counterproductive.

Throughout her life Marilyn took responsibility for her choices. And although I have kicked myself for not struggling with her more about this, it was her decision. In the face of our real powerlessness to reverse the outcome, her traumatic reality needs to be suffered, held, and borne.

But what we can refuse to accept — and work to change — is the incarceration of the remaining political prisoners. We can come together to free them and to try our best to make sure that no more die behind the walls. We can hold the repressive apparatus responsible. By doing so we contribute to a political and ethical environment that will help the untold resisters of today and the future who will undoubtedly rise and be jailed by our government. By holding the state responsible we challenge their vast, malignant system of social control that holds more than 2 million people: the majority of whom are poor and people of color.

keyword: She put her foot down and lived

Marilyn was out of prison for 20 days and in this time she lived to the loving limits of the possible. Miranda and I were honored to be able to visit her as I know others were. We brought the glorious quilt, Marilyn Freedom, made by women in the Bay Area, and presented it to her. I said, Marilyn you always were my John Brown. It pleased her when I thanked her for getting our comrades and me out of a Junction, Texas, jail in March 1969 (with a lawyer and bail) where we’d been held for a week.

We were on our way to the SDS national council meeting in Austin and were busted at a roadblock. Things looked like they might turn violent in a small town Texas way. She laughed in that knowing, sly way of hers. Miranda gave her a long massage and the three of us held each other in silence, sharing a deep recognition of love and farewell.

Now, months later, on fog-glistened evenings like this in San Francisco when I can only bear to be alone — and when solitude too is unbearable — great rip tides of grief keep on coming in as though pulled by the pull of the weeping moon.

The moon is water. A sob throws open windows to the monsoon. Fragments of breath drift off. A house of living spaces falls into silence; memories of Marilyn’s last year hurling past into that unforeseen horizon. Her-eyes-on us. I spray-paint the wall red: she deserved more.

From the websites and the blogs I feel the many who are weeping and honoring yet, in this same moment, can’t those who knew or met her even once hear her voice speaking directly without panic, as though she has not fallen?

If I could I would organize a demo of we small earthlings against her death and we’d storm heaven to return her to live among us.

Yesterday, the sky over the city was enormous. A woman in a wheelchair was shopping for marigolds at the farmer’s market. Open my eyes. The mirage builds itself; it is weightless and real.

Marilyn’s articulate face turns from a wheelchair backlit by the sun of freedom in Brooklyn.

I want to impress her face into the great wall of the universe so that she can be seen from all points, accessible deep into tomorrow.

In 2004, Marilyn wrote an essay, The Freedom to Breathe[6]

I am skinny-dipping. Stripping off my clothes, running into the water, diving down naked to disappear for a few breaths from the shouts and sounds of the world. Shedding clothes, embarrassments, care. The surface breaks as I return for air. For a few moments, I am free, opened, beyond place, beyond space…

Deepening my breath, lengthening my spine, I learn to discard my preconceptions and expectations – all the many hopes and fears and attachments that have given shape to my life. I learn to lay aside anxiety about what I am missing, what I do not have, what might happen to me in here. I confront the fact that I am, in truth, uncertain about whether I really want to release my fears, my anger. I am conflicted. Without the armor of my anger and self-righteousness, I become intimate with the many forms of suffering in this prison world – and so I feel vulnerable, exposed.

Each day presents a new confrontation with reality. I want to run; instead, I breathe. One breath – the freedom to choose my response in that moment. In sitting, I encounter joy; I know that through this practice I can arrive at a place of genuine peace. The path is before me. It is my choice to follow.

In the “everywhen,” which comes late at night when I cannot sleep, I see Marilyn walking under a wide canopy of amiable stars. She’s not in this world, but I can see her very clearly from here in San Francisco.

A woman of 62 years, whole, restored, vigorous, and trembling with excitement. She’s talking with other animated souls of the big-hearted revolutionary dead from all the ages that have come and gone on earth. They’re wondering together about how they might assist us.

I’m still running with her chimes of freedom.

[Felix Shafer became an anti-imperialist/human rights activist while in high school during the late 1960’s and has worked around prisons and political prisoners for over 30 years. He is a psychotherapist in San Francisco and can be reached at felixir999@gmail.com.]

- See “Felix Shafer: Mourning for Marilyn Buck, Part I” / The Rag Blog / January 13, 2011

- and “Felix Shafer: Mourning for Marilyn Buck, Part II / The Rag Blog / January 26, 2011

- Read earlier articles about Marilyn Buck on The Rag Blog.

Footnotes

[1]Two of Marilyn’s comrades, Susan Rosenberg and Silvia Baraldini together with Puerto Rican Independence fighter and teacher Alejandrina Torres, were held in the underground Lexington (Control) High Security Unit, which was condemned by Amnesty International and denounced as a psychological torture center by the campaign which eventually forced its closure of in 1988. As this unit was being forced to close, the Bureau of Prisons was building many more control unit prisons. See the 1990 documentary film, Through the Wire, by Nina Rosenblum, on PBS.

[2]On Self-censorship, by Marilyn Buck. Published by Parenthesis Writing Series. ISBN 1-879342-06-5. 1991. Currently out of print.

[3]See her CD: Wild Poppies available from Freedom Archives & chapbook: Rescue the Word available from Friends of Marilyn Buck at marilynbuck.com

[4]Her poetic collaborators intend to see Inside Shadows published by a major poetry press sometime in 2011. This is one aspect of our continuing collaboration with Marilyn. Check www.marilynbuck.com for this and other important ongoing information.

[5]A growing number of U.S. political prisoners have died of cancer and other illnesses in prison. An incomplete list: Albert Nuh Washington, Kuwasi Balagoon, Merle Africa, Teddy ‘Jah’ Heath, Richard Williams, and Bashir Hameed. Others have faced and are facing life-threatening challenges both inside and after release on parole.

[6]Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Vol. XIII, No.3, page 84, Spring 2004

This is the meat and heart of this beautiful early assessment of the life of Marilyn Buck, and I am so grateful to Felix for writing it and sharing it here.

To find freedom regardless of one’s circumstances, and to fight for freedom for all who are oppressed without thought for one’s personal safety, these are the attributes of a hero.

Since Felix sent the Rag Blog this essay, published here in 3 parts due to its length, there have been a few new developments. For one, a fund has been established in Marilyn’s name to concretely help the very many remaining political prisoners from the 1960s, 70s, and 80s who are still languishing in jails all over the country. More information about the fund is available at http://www.marilynbuckpresente.org, along with poetry and many other tributes to Buck.

In Austin, among the annual poetry awards of the Austin Poetry Society this year is an award for poetry of resistance and repression, in Buck’s honor, details at http://www.austinpoetrysociety.org; first prize is $100 (and I am ineligible)!

Finally, in the present spirit of freedom sweeping the MidEast, I know I am not alone in seeing, perhaps, the weight of Marilyn’s spirit on the cosmic scale; she was an ardent supporter of the Palestinian people but more importantly, of the dignity and individual worth of the women and men of all countries. She introduced me (and many others) to the transformative literature of middle Eastern women writers, especially, whose involvement in the present struggles is daily an encouraging sign.

Interesting read, the story covers an awful lot of social and political history and something about the attitudes and interests Marilyn developed deep into her incarceration. As biography, I think it comes up a bit short, however.

The question that Marilyn’s life raises for some of us – I had a passing acquaintance with her circa 1969 or so – is why she turned to shooting and bombing in the first place.

If she hadn’t bought the ammo for the BLA, she wouldn’t have been sentenced to her first term in prison, and if she hadn’t turned to bombing, she wouldn’t have drawn the second one. And yes, the sentences were too long – the first one especially – but emphasizing length of sentence is talking about what was done to her rather than what she chose to do, which reduces her to a victim.

My take, based on limited contact, is that Marilyn made the mistake of believing that the rhetoric of revolution that the Chuckwagon radicals bandied about was supposed to be taken seriously. It drove her nuts that all these people who were comfortably jabbering away about worker student revolutions, radical youth revolutions, and black/brown/white revolutions weren’t acting in accordance with their professed beliefs. She took all that stuff to heart, while the people who are generating the noise obviously weren’t serious about it. So she went and joined the most radical folks she could find and took on the closest approximation she could find of the revolutionary’s life style.

In a very real sense, Marilyn wasn’t just engaged in struggle with the overlords of the capitalist ruling class, she was even more deeply engaged in struggle with the elements of a movement that lacked sincerity and commitment. In that sense, she wasn’t as much a victim of the state as she was of the empty and loose rhetoric of the time.

It’s hard to mount a serious argument – knowing what we know today – that the US is in need of a violent revolution, that any of the preconditions of revolution have ever existed here since the rise of the industrial economy or the post-industrial one, or that such an adventure would have any likelihood of turning out well. But Marilyn didn’t know these things in 1969, and she came by the lessons the hard way.

What I take away from her life is the importance of separating truth from fiction, the serious from the unserious, and the importance of seeing other people and one’s own self as individual human beings first and as members of groups, categories, and classes second (or third, or fourth.)

Yes, it’s true that Marilyn sacrificed a great deal of her personal life for the causes she believed in. But what kind of cause requires people to do that, and how good can a cause be that depends on total sacrifice to achieve its ends? I’d say this is a caution to young people to avoid movements that require the total subjugation of individuality. Sound judgment only comes from people who are sound in all dimensions of life, not from those who monastically pour themselves into stereotypical roles in order to teach lessons to the rest of their movements and of humanity at large.

It’s tragedy that a woman with Marilyn’s intelligence, energy, nerve, and commitment had to spend most of her adult life in prison; she could have accomplished so much more on the outside. But this tragedy came about because of a series of bad choices she made early in her life, not simply because the state over-reacted to her actions.

You fail to mention this is a convicted murderer and terrorist.

A sweet member of my family would have loved to have died at home surrounded by friends and love ones. Thanks to this murderous, evil, bitch and others….. he didn’t have that choice.

Rot in hell Marilyn.