THE MACHINE

By Marc Estrin / The Rag Blog / September 27, 2011

The government murder of Troy Davis this week — under odd evidential circumstances — has once again thrust capital punishment up for public discussion.

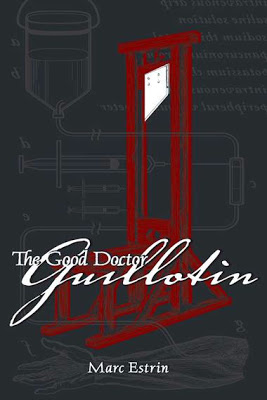

As my contribution to death penalty abolition, I recently wrote The Good Doctor Guillotin, a novel about the first use of the guillotine during the French Revolution — an occasion sufficiently removed from current politics as to allow the issues to be seen more clearly.

Tobias Schmidt was the machine’s builder, a piano maker. And Charles-Henri Sanson was the executioner of Paris.

The novel itself is intricately woven, but here’s a stand-alone short chapter describing the testing of the machine before use. It may provide some food for reflection:

29. The Machine

It was 14 feet high, its beams and posts painted blood-red — a nice touch, that. It would be called “End of the Soup,” “Old Growler,” “Sky Mother,” “the Last Mouthful.” It would be called by the feminine form of someone’s name, someone who had repudiated it. As if it were his daughter. Assemblymen called it the “Timbers of Justice.”

The victim, once attached to the plank, his head in the fatal window, would become a part of it, a cog in the machine of egalitarian justice. His blood would be shed not by the unsteady hand of his fellow man but by this lifeless, insensible, infallible instrument, a doctor’s idea become oak and iron.

The materials gathered, over the course of a week Tobias Schmidt and two hired workers constructed the frame. Two four-sided posts were grooved and chiseled as guides for the falling blade. When the 70-pound holder and 15-pound blade came back from the blacksmith, they were fitted loosely between the posts and the posts joined by an upper crossbar with a hole for the rope. A lower crossbar was angle-braced to its stand for stability. Rope guides were placed.

On the back side of the device, the executioner’s side, another crossbar was attached to hold the lunette — two wooden pieces, each with a half-circular hole to contain the client’s, the patient’s, the package’s neck. The diameter was that of Pelletier’s. A smaller one for women could be substituted as needed. When fitted together, the pieces formed a lovely “little moon” whose upper half could be lifted on a hinge to permit a head to enter.

That was it. Simple. A weighted blade and its frame. Though it required two strong men to carry it, it could be loaded onto a heavy cart and transported wherever it was needed, along with its separate bench, long and strong enough to hold a giant—or an ox—and fitted with thick leather straps.

Before dawn on Tuesday, April 15, 1792, a sound of clattering wheels was heard on southern streets two miles from the center of Paris. It was a four-wheeled wagon, drawn by two horses, carrying a long object covered with heavy black cloth and tightly bound with chains. Four guardsmen with bare swords on horseback rode silently in front of the wagon, and four behind. Bringing up the rear was a smaller wagon with several sheep. If going to market, they were being taken in the wrong direction. They advanced slowly, gray and black in the pale early morning.

The procession was heading for the suburb of Bicêtre, just outside the city gate, home to the great hospital for venereal disease, its hospice for the needy poor, and its maison de correction, locked wards for hardened criminals, some awaiting execution.

When seen from a distance, Louis XIII’s building looks quite imposing. Set on the brow of a hill, from afar it retained something of its former splendor and the look of a royal residence. But now, three Louises later, the palace had in fact become a hovel. Its dilapidated eaves were shameful and its walls diseased. Not a window was glazed but only fitted with crisscrossed iron bars through which, here and there, pressed the harrowed face of a patient or a prisoner.

Already waiting in a small inner courtyard were Charles-Henri Sanson, with two assistants, Tobias Schmidt, and the doctors Antoine Louis and Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, the latter most reluctantly.

Early-morning eyes gawked from behind bars as the first sheep’s head was placed in the lunette, its neck the size of Pelletier’s. The upper half moon was locked in place. One of the assistants let loose the rope from its tie-off so Sanson could better observe.

Disaster: The heavy blade jerked stickily into motion, jolted downward between the grooves, and sliced into the animal without killing it. All mental ears were stopped against its terrifying cry. Sanson was dismayed. He had the blade wound back up and released again. It bit into the neck again but did not sever it. The victim howled. Once again the blade was raised and dropped, but the third stroke only caused a stream of blood to spurt from the sheep’s neck, without the head falling.

Five times the blade rose and fell; five times it cut into the sheep, which cried five times for mercy. It remained standing on the platform, an appalling, terrifying sight. Sanson straddled it and hacked away with a butcher knife at what remained of its neck. Twenty pounds of lead shot were added to the blade-carrier, and three more sheep were neatly dispatched thereby. The march of science.

After nightfall Schmidt took the machine back to his workshop in the Cour du Commerce, Rue St.-André-des-Arts, just opposite the printing shop in Number 8 where Marat’s paper was printed. He lined the grooves with brass for a smoother drop and bolted more weight to the blade assembly.

Two days later, on April 17, assisted by his son and his two brothers, Sanson repeated his experiments on the improved machine, this time with three human cadavers from a military morgue, three well-built men who had died in short illnesses that had not caused them to grow thin.

Among the spectators were the two doctors concerned, along with Michel Cullerier, the chief surgeon of Bicêtre; Philippe Pinel, the resident alienist; several physician members of the National Assembly; and delegates from the Council of Hospitals of Paris. Strapped to the bench, the three corpses, good soldiers all, were successfully beheaded without protesting, to the applause of most of the onlookers.

[Marc Estrin is a writer, activist, and cellist, living in Burlington, Vermont. His novels, Insect Dreams, The Half Life of Gregor Samsa, The Education of Arnold Hitler, Golem Song, The Lamentations of Julius Marantz, and The Good Doctor Guillotin have won critical acclaim. His memoir, Rehearsing With Gods: Photographs and Essays on the Bread & Puppet Theater (with Ron Simon, photographer) won a 2004 theater book of the year award. He is currently working on a novel about the dead Tchaikovsky. Read more articles by Marc Estrin on The Rag Blog.]