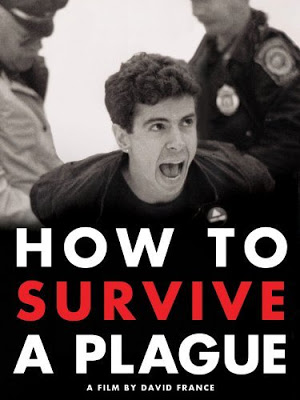

How to Survive a Plague:

The remarkable story of ACT UP

Panic spread slowly. Rock Hudson’s death gave the disease a public face, but took us no closer to the cause.

By David McReynolds | The Rag Blog | April 10, 2013

[David France’s critically-acclaimed and award-winning documentary film, How to Survive a Plague, saw limited release in the United States in 2012.]

Clancy Sigal’s advice to me is to keep it short — a skill he has mastered and I’ve not. This is a quick review of David France’s film (now on DVD), How To Survive a Plague, largely the story of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and TAG (Treatment Activist Group), the nonprofit organization that grew out of ACT UP.

As films go, this feels almost like a “rough draft” of a documentary, but how could it be otherwise? The technical limitations of this short documentary are overwhelmed by a remarkable story, one that makes the film worth watching by anyone concerned with social change. The producers had to hunt for bits and pieces of film over a period of years — this was not a film which had been assigned a staff photographer to follow events.

I’ve said to friends that if I were 10 years younger I’d have been dead long ago — but when AIDS was given a name, in 1982, I was already 53. It wasn’t just a “gay disease” — it was almost entirely a disease of the youth. It’s first name was GRID — Gay-Related Immune Deficiency — and even when it was given a name a year later, no one had any idea what caused it. Panic spread slowly. Rock Hudson’s death gave the disease a public face, but took us no closer to the cause.

My local bar — once probably the best gay bar in New York, right on my corner, at Fourth Street and Second Avenue — slowly emptied out. Bob, the sweet young bartender, fell ill, and then fell dead. Bar traffic slowed, as if perhaps breathing the same air would transmit the disease.

By 1987 ACT UP was formed. It had the enormous energy of youth. Watching this film reminded me, again, of why the young are almost always the cutting edge of social change. They are not always right — ACT UP made more than its share of errors, suffered the almost inevitable splits — but to watch this film is to see young men and women, frightened by the death which was marching straight towards them, organize and act. And to act with imagination and love — in things such as the moving “quilt” project.

They provided the people-power for major political demonstrations, but they did much more than that — they studied the disease, they examined alternative treatments, and methods for running trials that would speed up the information on what might work. In the end they cooperated with the scientists in finding the answer.

And that answer was not easy to find. The AIDS virus is remarkably tricky and defeating it has been an incredibly complex task. It was, for the men and women in ACT UP, a race against time.

Watching the film I felt a sense of guilt that I had not been more involved. AIDS, even though we didn’t know its cause, was around me. A neighbor who lived a floor above me came down with it, and while I was able to visit him at first, simply walking into his room (he had Kaposi’s Syndrome), when he was taken to the hospital his room was guarded as if a particle of the disease might escape. One had to put on gloves, mask, a gown before going in, and they were taken off and destroyed when you left his room.

All of us have sins of omission; I won’t belabor mine. I write this brief review because the beautiful young men and women in this film, so vital, so very young, so fierce in their struggle, and most of them now dead, succeeded in pushing until the labs delivered the drugs which have made it possible to defeat AIDS.

It isn’t, of course, defeated, not here (where unsafe sex is sometimes seen as exciting), much less in Africa. But because of ACT UP we have the means. The film, made in 2012, is one hour and 49 minutes. You can get it from Netflix.

[David McReynolds was for nearly 40 years a member of the staff of the War Resisters League, and was twice the Socialist Party’s candidate for president. He and the late Barbara Deming are the subjects of a dual biography, A Saving Remnant, by historian Martin Duberman. David retired in 1999, and lives on the Lower East Side of Manhattan with his two cats. He posts at Edge Left.org and can be reached at davidmcreynolds7@gmail.com. Read more articles by David McReynolds on The Rag Blog.]