‘This androgynous Jersey girl obsessed with Rimbaud and Shelley and Whitman came to the big city 40 years ago’

By Andrew O’Hehir / August 6, 2008

Almost at the beginning of Steven Sebring’s documentary “Patti Smith: Dream of Life,” a film and art installation and photography book that have been 12 years in the making, we hear a narration from the eponymous rock goddess-poet, declaiming a short version of her life story in her husky, incantatory contralto. As Sebring shows us black-and-white images of a train journey, perhaps suggestive of the journey Smith once took from rural southern New Jersey, where she grew up, to New York, where she would make her name — and perhaps suggestive of the journey from birth to death — Smith breaks it down.

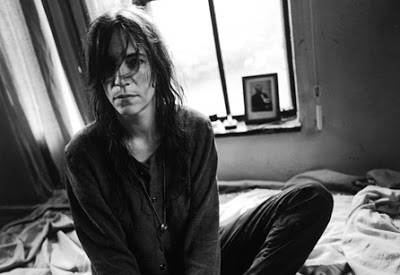

Quite a life it has been: This androgynous Jersey girl obsessed with Rimbaud and Shelley and Whitman came to the big city 40 years ago and became the muse and friend and partner of Robert Mapplethorpe (no adequate English word exists to describe their relationship), became a poet and then a performance poet and then an underground rock musician and then a rock star, left the stage and the city for life in Michigan as a wife and mother, and then, after the 1994 death of her husband Fred “Sonic” Smith, returned to New York, to music, to poetry and to political activism. Sebring’s film, so long in gestation that it became a major life event for both its director and its subject — one observer opined that the film would only be finished when one or the other of them died — offers an intimate, impressionistic portrait of this later Patti Smith, a woman still blazing her own trail through late middle age, a woman who has seen and suffered much loss and who is perhaps the only major surviving link from the beat era to the ’70s Manhattan art scene to the birth of punk to the present.

Whether this is a flaw is up to you, but Smith’s opening narration provides the only backdrop or exposition we ever get in “Patti Smith: Dream of Life.” Sebring offers a concert film — capturing parts of Smith’s 2005 London performance of her first album, “Horses” — and a travelogue and a chronological voyage; much of his footage (most of it in black-and-white) is beautiful and Smith herself, so often described as a prickly or difficult person, is delightful company. But we often don’t know where she is in space or time, and if we figure that out, we’re not sure what she’s doing there or why. It’s a disorienting whirl from New York to Tokyo to London to Paris to Rome to Atlanta to New Jersey, which I guess is the point.

You could almost say that the tremendous passage of time in the film is itself the point. Smith is visibly, almost geologically older in what appears to be the film’s present tense, an interview in her room at the Chelsea Hotel. (She’s now 61.) Her two children, Jackson and Jesse, are scraggly moppets in some scenes and almost adults in others. Smith’s visit to south Jersey is of course a trip to see her elderly and charming mom and dad, still living in the same aluminum-sided Cape Cod where she grew up. Except that they’re not anymore; both of them died before Sebring could finish the film. (It goes unmentioned here that Smith’s biggest hit, “Because the Night,” was co-written with another New Jerseyite from nearby Asbury Park, so I’ll bring it up for no special reason.)

That’s what goes with the passage of time, of course; everybody gets older and all of them eventually die. Smith talks about her relationships with William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso and her husband Fred Smith and her brother Todd Smith and her keyboard player Richard Sohl, all of them gone. (We hear Fred Smith singing one of his wife’s songs, in a home recording made during his final illness.) She visits Corso’s grave in Italy and Rimbaud’s grave in France and Shelley’s grave in England; the title of Sebring’s movie, and of Smith’s 1988 album, comes from Shelley’s oft-quoted “Adonais”: “Peace, peace! he is not dead, he doth not sleep — he hath awakened from the dream of life.” (Isn’t that exactly what Mick Jagger read onstage at the Hyde Park concert after Brian Jones’ death? It’s not just poetry, it’s rock history!)

Perhaps for comic relief, another living megasaur of ’70s counterculture, Sam Shepard, shows up briefly to jam, atrociously, with Smith on acoustic guitar. Honestly, I don’t know what that scene is doing here; it’s the one moment — well, along with hugging Jesse Jackson backstage at an antiwar rally — that feels like conventional rockumentary. Smith’s activist career gets fairly short shrift in the movie, although it’s an important facet of her recent life. Sebring may not want to remind people how avidly Smith campaigned for Ralph Nader in 2000.

“Patti Smith: Dream of Life” is frequently beautiful and intermittently haunting and could be called a meditation on aging and mortality, an intimate study of a peculiar variety of fame and a portrait of a genuinely remarkable person. It has played at Sundance and Berlin and all over the film festival world, at least in part because everyone’s so amazed it actually got finished. Still, while “Dream of Life” succeeds on its own terms, I can’t help feeling there’s a missed opportunity here, an opportunity to make clear to younger women and men just how amazing Patti Smith’s journey has been. (Maybe, like Julien Temple’s wonderful “Joe Strummer: The Future Is Unwritten,” that kind of film can’t be made while the subject is alive — but I’m not quite sure why that would be so.)

Two decades before the riot grrrls, Smith behaved as if she never even knew that women weren’t supposed to rock, weren’t supposed to have big egos and sexual adventures and write thundering, self-indulgent post-beat poetry. Her albums “Horses” and “Radio Ethiopia” were far ahead of the ’70s rock curve, and to this day remain among the rare fully successful hybrids of rock and poetry. Even as she was being a feminist trailblazer, the younger Smith had a unique Manhattan-hipster ability to be at the center of the action, whether that meant Mapplethorpe’s studio or Burroughs’ booze sessions or Shepard’s plays or CBGB’s with the Ramones, Television and Talking Heads. (She closed that club forever with a three-and-a-half-hour performance in October 2006.) Almost none of that — OK, none at all — is visible in this film, except by inference and reference. If you don’t already think that Patti Smith and the people she hung out with are awesome, this movie won’t tell you about it.

One of the greatest things that can be said about Patti Smith, I think, is that although she was either an inventor or a precursor of punk (depending on how you look at it), it rapidly bored her and she moved on. She couldn’t be contained by any movement or ethos or ism, and anyway was always closer to being Rimbaud or Ginsberg than to being Billy Idol (or, for that matter, Joan Jett), and by the early ’80s she was married and living in suburban Detroit. Her great triumph was not that she was a female rock revolutionary, or that she left music for a domestic life, or that she came back to it when that domestic life ended. It was that she never questioned her right to live her life exactly as she saw fit, to make it up as she went along in the great tradition of all those dead white male artists she worshiped. As Sebring’s film makes clear, she’s still doing that today.

“Patti Smith: Dream of Life” is now playing at Film Forum in New York, and opens Sept. 19 in Columbus, Ohio, and Denver; Oct. 2 in St. Louis; Oct. 17 in Los Angeles and San Francisco; and Oct. 24 in San Diego, with more cities to be announced.

Source / salon.com

Can’t wait to see this film! When is it in Minneapolis!?

Anyone see the Germs movie “What we do is secret”?