The documentary form is only now realizing the possibilities foreshadowed by its beginnings.

By William Michael Hanks / The Rag Blog / June 2, 2009

Also see Turk Pipkin’s Remarkable ‘One Peace at a Time‘ by William Michael Hanks / The Rag Blog.

The release of Turk Pipkin’s One Peace at a Time provides an excellent opportunity to reflect on the evolution of the documentary film

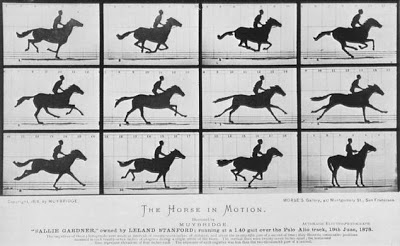

The documentary form is only now realizing the possibilities foreshadowed by its beginnings. As early as 1874 photographers were experimenting with taking a series of still pictures that, when rapidly displayed in sequence, came to life in motion. Eadweard Muybridge arranged a row of still cameras along a horse track. As the horse ran along the track a series of tripwires connected to the cameras took individual photographs.

In Nobelity Turk interviews Ahmed Zewali, Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He is looking at events at the level of molecules. He refers to Muybridge and remarks that his photos were capturing pictures at 1900 milliseconds. Current technology enables capturing pictures in 200 millionth of a billionth of a second.

The motion studies of Muybridge demonstrated the foundation of the documentary: “its ability to open our eyes to worlds available to us… but not perceived.” (Erik Barnouw, Documentary: A History of the Non-Fiction Film) Specialized cameras and film were soon developed for the purpose of capturing moving images. Lumiére in France and Edison in America were pioneers in the production of equipment and exhibitions.

From its inception, the documentary has held a tenuous relationship with the popular cinema. Between 1896 and 1907 almost all motion pictures were documentary films. Reels limited running time to a few minutes. Titles of the day included Arrival of a Train, Gondola Scene in Venice, and The Fish Market in Marseilles.

By 1912 documentaries were in decline. The increasing use of staged sequences such as The Coronation of Elizabeth II and Charge up San Juan Hill diluted its significance. The increasing production of fiction films, The Great Train Robbery often cited as the first, and the establishment of the commercial studio system relegated the documentary form to a diminishing role in popular taste. The documentary was not financially viable.

After the initial decline of the documentary only the newsreel and travelogue kept the form alive. Notable exceptions such as Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North and the agitprop films of Dziga Vertov in Russia began to foreshadow the future of documentary –- the ability to bring us closer to real people and significant events.

In choosing the “road movie” or travelogue model in Nobelity and One Peace at a Time, Turk connects us with the one form of documentary that has survived intact from the beginnings of documentary film. Even when other forms were in decline, the travelogue remained viable.

The documentarists of the 1940s through the 1960s struggled continuously with the limitations of technology. The size and weight of cameras and recording equipment and the sensitivity of film required large crews, limited the shot possibilities, and demanded extensive lighting to produce.

In the 1970s portable video equipment began to offer hope that the potential of the documentary form might be fulfilled. The cost of professional video equipment remained an obstacle to wide use but in recent years even that difficulty has been overcome with the arrival of light, self-contained and high-quality camcorders.

As the technology available to the documentarist has evolved so has the art and technique. The predominant narrative technique of the 30s and 40s was the “voice of god.” An off-camera narrator explained in dramatic tones what was seen onscreen as in The Plow That Broke the Plains and Victory at Sea.

By the 1960s the techniques of French cinema verité moved the viewer closer to the subject creating a more immediate experience. The “fly on the wall” technique, which sought to eliminate the perception of the camera and narrator, told stories in the first person only. These techniques sought to further immerse the viewer in the events.

An evolutionary improvement of the first-person technique is the presence of an on-camera guide –- a narrator to bridge and give meaning to the sequences. A further evolution is reflexivity, which reminds us that we are seeing a film, and further engages us in the experience.

Examples of reflexivity are Turk’s acknowledgement of the production process such as holding a door open for the camera, including the camera in the shots, and his conversational awareness of the viewer. Dziga Vertov, Luis Buñuel, Alfred Hitchcock, and others use this technique effectively to involve the viewer more organically in the experience.

Taken together, the availability of lightweight high quality equipment, the use of first person narrative, spontaneity of movement, music and sound, and low cost digital distribution has finally freed the documentary from it’s early confinement and makes the form available to anyone who has the desire to inform, inspire, and create understanding. Follow Turk’s example, see the film, choose a cause, get a camcorder, and document your project to save the world!

UC Berkeley — Media Resources Center

Chronology of Documentary History.

International Documentary Association

See outstanding documentaries online.

[William Michael Hanks has written, produced and directed film and television productions for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, The U. S. Information Agency, and for Public Broadcasting. His documentary film The Apollo File won a Gold Medal at the Festival of the Americas. William Michael Hanks lives in Nacagdoches, Texas.]

The Nobelity Project and One Peace at a time are remarkable works. This excellent article and the film it descibes deserve the widest possible audience. Props to Mr. Pipkin, Mr. Hanks and the Rag Blog.