Celestial Stars and Stripe Revealed in Hubble Image

Irene Klotz / July 3, 2008

About 700 years before the birth of America, a dying star exploded, creating a shock wave that blasted through space at nearly 20 million m.p.h. for the next thousand years.

Initially, the burst of light was so bright that it could be seen in daylight on Earth, nearly 7,000 light-years away in a constellation known as Lupus.

Radio telescopes picked up its trail in the 1960s with the discovery of a nearly circular ring of material in the general area of where the supernova had occurred. It wasn’t until 1976 that astronomers had a powerful enough observatory in the southern hemisphere and the good luck to pick up another visual.

On the northwest edge of the radio ring, the shock wave had reached a part of space sprinkled with hydrogen atoms, causing them to radiate in visual light.

“It’s kind of like a sonic boom,” said astronomer Frank Winkler with Middlebury College in Vermont. “Your ears clearly detect that as a change in pressure. In the case of the supernova, this shock wave has been propagating outward from the site of the explosion for a little more than 1,000 years now.

“One of really interesting things that happens is that behind the shock wave, some of these hydrogen atoms, which are essentially bare nuclei, are really fast-moving — a few thousand kilometers per second — so if you have a collision between one of these and an unsuspecting neutral hydrogen atom that suddenly finds itself right behind the shock wave, they can trade electrons,” he said. “The fast-moving one gloms on to the other’s electron and that leads to the emission of a photon.”

The Hubble Space Telescope picked up the trail 30 years later with a series of observations, culminating in the release this week of a picture to mark Independence Day.

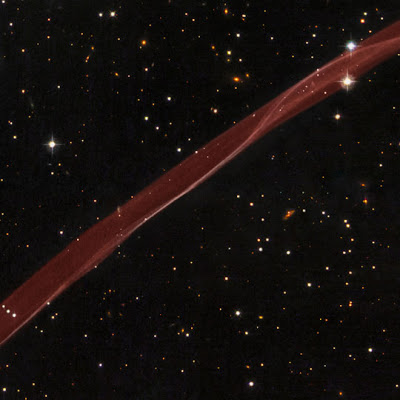

The celestial version of the stars and (a) stripe show orange-hued points of light that are background galaxies and white dots which are background and foreground stars in our own Milky Way.

The bold red ribbon of light is a tiny portion of the tenuous hydrogen gas being heated by the supernova blast wave. The bright spots are areas where the shock wave is edge-on to our line of sight. Hydrogen’s glow is mostly in a deeper red hue so the Hubble team shaded it a bit more orange to make it easier to see.

The supernova, known as SN 1006, is 60 light-years in diameter and still growing at a rate of about 6 million m.p.h.

Source. / Discovery News

The Rag Blog