Why The ‘Right’ Gets Net Neutrality Wrong

By Art Brodsky / May 5, 2008

Just in time for the House Telecommunications Subcommittee’s hearing tomorrow (May 6) on Net Neutrality legislation, former House Majority Leader Dick Armey (R-TX) and the American Spectator are out with new attacks on the simple idea that people should not have their Internet experiences subject to the whims of telephone and cable companies.

My day-job employer, Public Knowledge, even achieved a new level of notoriety when we were prominently mentioned in a blog post on the American Spectator, the publication best known for funneling millions of dollars to investigations of Bill and Hillary Clinton.

The April 28 blog post, cleverly headlined, “Public Know Nothings,” — a play on Public Knowledge — read like a basic corporate hit job on Net Neutrality of the kind one might read at any number of blogs or by any columnists in the thrall of the corporate world. But the story, combined with Armey’s April 22 Washington Times headlined “Spare The Net,” raise the inevitable question — what is it about individual freedom that “conservatives” like the Spectator and Armey don’t like?

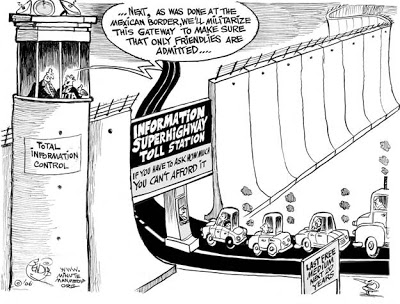

To be fair, the debate is larger than the Spectator and Armey. Most congressional Republicans oppose the idea of giving consumers freedom on the Internet. They take shelter in their anti-government, anti-regulation rhetoric, preferring to allow Internet freedom to apply to the corporations which own the networks connecting the Internet to consumers, rather than to consumers themselves. There could, of course, be a larger discussion about the meaning of “conservative” and Republican, and whether the two are synonymous.

(To be fairer still, it’s not only Republicans. Many a Democrat also speaks out against Internet freedom. They don’t have the fig-leaf of misbegotten ideology to hide behind, as they largely back worthwhile government action in many other areas. They are simply servants of corporate and/or union interests. The question applies equally: What about freedom don’t they like?)

The clues to discovering how the opposition to individual freedom came about are in the two recently published pieces. Each them, in their own way, shows a tragic misunderstanding of how telecommunications policy, markets and technology worked in the past and how they work today. As a result, their interpretations of Net Neutrality, and the role of government, are also wrong.

At the heart of the opposition is the “mythology of the market,” that once government “got out of the way,” as Armey put it, new technologies emerged. “Telecom became a text-book case demonstrating that markets work and are good for consumers,” as the Internet developed and dial-up modems yielded to broadband connections, Armey wrote.

Similarly, Peter Suderman, writing on the Spectator site, misses his telecom history. He criticized the testimony of actor and Internet entrepreneur Justine Bateman, who spoke to the Senate Commerce Committee about the need for a free and open Internet. Bateman asked whether Google and eBay would have been as successful as they are “without the freedoms we enjoy on the Internet today.”

Suderman’s analysis: “In fact, not only were all of these companies [eBay and Google] born in an era with no mandated net neutrality, it’s utterly unclear that a lack of neutrality would’ve impeded them in any way whatsoever.”

Government Helped Create The Internet

Let us review the history. Even setting aside the very basic fact that the underlying technology for the Internet was created under a government program, and was set free for commercial purposes by Congress, it’s still hard to get away from the reality that the Internet as we know it was started, and flourished, in a regulated environment. While the content that went online, through bulletin boards, America Online, CompuServe, Prodigy and the rest, wasn’t regulated, the telecommunications carriers to a large extent were.

Before the advent of the cable modem, the telephone companies that carried the online traffic not only were under tight rate-of-return regulation, but they were also subject to the sections of the Communications Act barring unreasonable discrimination (Sec. 202). They also had to sell their services wholesale. Amazingly, with all of that regulation, the first iteration of the online world grew, with thousands of local Internet Service Providers able to afford access to the network so they could offer their services to the public.

The new and fancy equipment came because the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 1968 broke through the tariff of then Bell System and allowed outside, customer-owned devices to be connected to the network. That decision brought competition in long distance as well as setting the stage for the fax, modem and other gadgets.

For the record, eBay was founded in 1995. Google came along three years later. It wasn’t until 2002 that the FCC under Chairman Michael Powell started the process of classifying nascent cable-modem service as an “information service” under the 1996 Telecommunications Act. Both cable and DSL were taken out from under most regulations by the FCC in 2005, when today’s Internet took shape. That decision, combined with some archaic, in-the-weeds technical matters, combined to wipe out the hundreds of local online and Internet Service Providers along with most of the competition for the telephone companies. One of the rules swept away was the prohibition against unreasonable discrimination — the part of the law that enforced what we now know as Net Neutrality. That’s what the proponents of a free and open Internet are trying to reclaim. It’s very simple — those companies carrying traffic can’t play favorites.

Google’s founders have said repeatedly they wouldn’t have been able to get off the ground if they had been required to pay extra fees for telecommunications services to get onto a “fast lane” of service.

Market-Based Myths Abound

The argument against Net Neutrality really goes off-track when it gets into the nature of private property, the state of competition, and the effect of regulation. That’s more than one track to be thrown off of, so it’s quite the disaster scene. We may need CSI: Telecom to sort it all out.

Public Knowledge earned its headline in the Spectator because of the petition we filed with the FCC asking that companies like Verizon which offer text messaging not be able to decide which groups should be deemed worthy of service and which shouldn’t be.

Read the rest of it here. / The Huffington Post

Also see Net Neutrality by Christopher Kuttruff / truthout

The Rag Blog